“I didn’t know what an engineer was until I got to college,” said Jason Coleman, executive director and co-founder of Project SYNCERE — a nonprofit dedicated to project-based learning in STEM for underrepresented students in Chicago, Illinois.

“I was really good at math and science growing up, but I had no mentors to expose me to engineering” he said. “I went to some of the best schools in Chicago, but they really didn’t push engineering towards me. My teachers didn’t recommend it to me.”

When he got to college, Coleman initially thought he would be pharmacist, but he disliked his first chemistry class and saw that a lot of his friends were studying engineering.

“They kind of showed me what engineering was all about,” he said. “And then once I became an engineer, it forever changed my life.”

For Coleman, however, one thing remained the same. Whether in his classes or over nine years working for engineering companies, he was typically the only black male. (For reference, Michael McGarry, CEO of PPG, wrote in the Pittsburgh Gazette that “less than 2 percent of black freshmen in the United States enter college engineering programs.”)

“I really wanted to change that whole dynamic,” Coleman said. “I knew there were other students like me who were really smart in math and science and who could succeed if they only had the chance to become exposed to these careers early on.”

So Coleman and two of his childhood friends decided to do something about it. They started by quitting their day jobs (Coleman was at Motorola at the time).

“We went full in,” he said. “We left Corporate America to start the organization to really try to help inspire more young people … to become not only engaged in the STEM fields earlier on, but really provide them with a lot of tools and resources they need to be successful once they get to college and later on in life as well.”

The nonprofit, Project SYNCERE (which stands for Supporting Youth’s Needs with Core Engineering Research Experiments) launched in 2009. Over the last 10 years, the organization has developed several educational partners — including City Colleges of Chicago and Chicago Public Schools — as well as corporate partners like Boeing, Lenovo, Microsoft, Motorola Solutions, and more.

Project SYNCERE serves 3,500 underrepresented students each year through both in-school and out-of-school project-based programs. Last Monday, Coleman made a site visit to Southeast Area Elementary School to see seventh graders in a Project SYNCERE class firsthand (Chicago Public Schools are generally K-8 for elementary). The school’s student population is nearly 96 percent Hispanic.

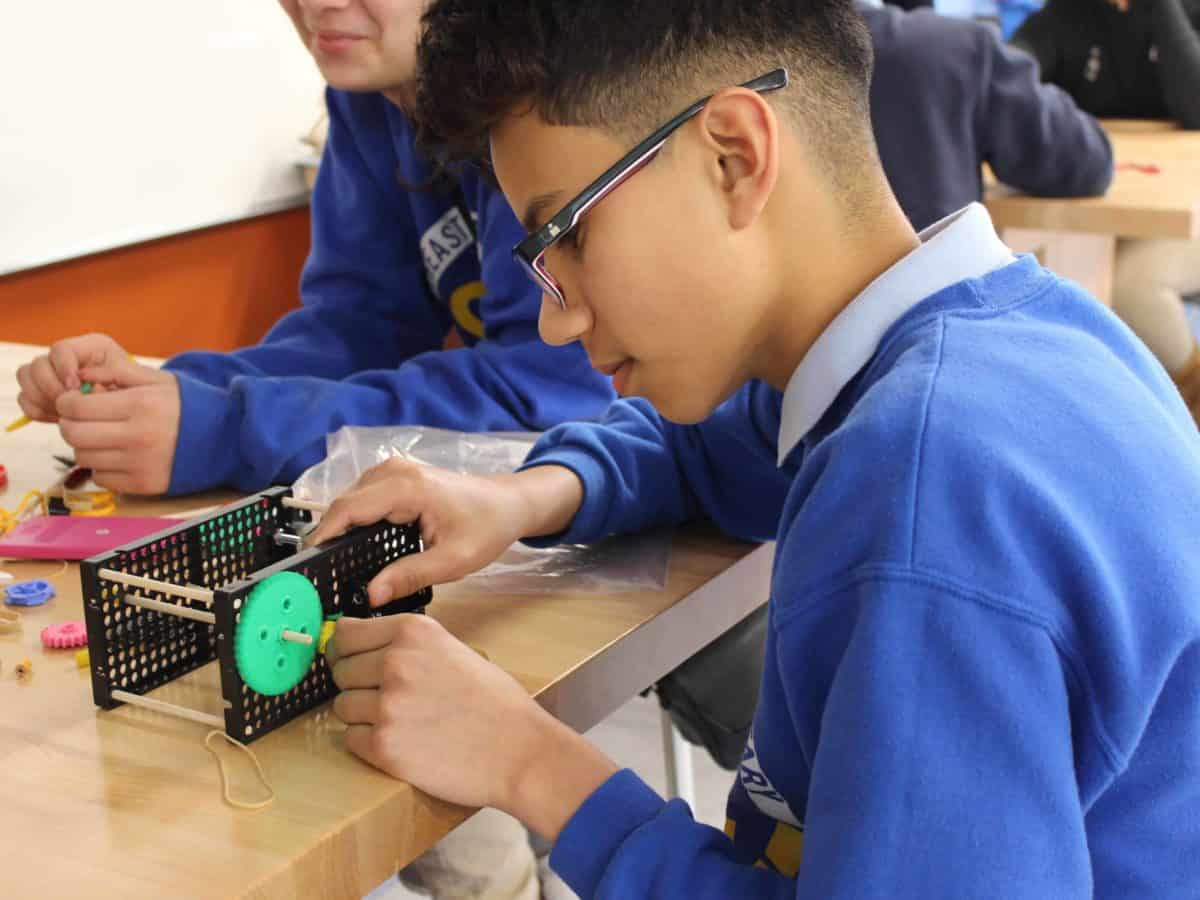

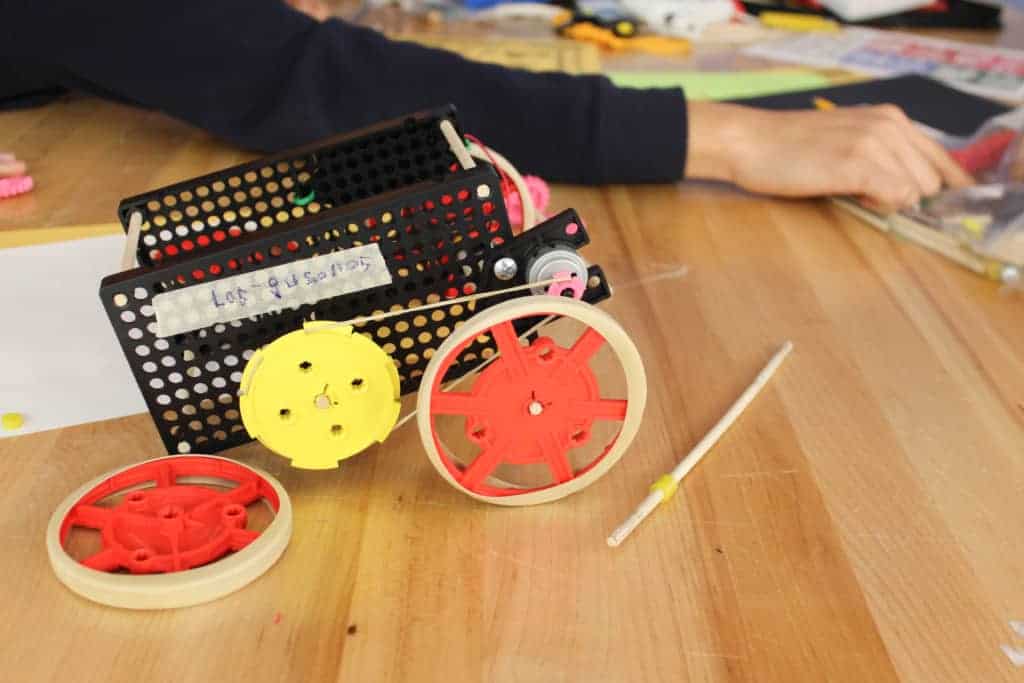

Students worked in groups on DC-motor cars, with each group assigned a different sized gear set to test how gear size affects speed. The class was led by Project SYNCERE Engineer Facilitator Candace Young, who held a brief introduction of the activity at the beginning of class. The rest of the class period, students tinkered with the set up of their cars and timed how fast the car moved over three meters — all under minimal to no direct instruction.

“What I do within the classroom is not just make sure that they know how to play with the toys, but to also be able to do this on their own,” Young, who is also a chemistry major at Chicago State University, said. “We are basically enticing them to use their own brain, use their own creativity to build things and to make things work.”

This method is part of the preparation for Project SYNCERE’s Enpowered Games, a day-long engineering competition for 400 middle-school aged students representing 20 Chicago schools.

“It gives them an opportunity to … see other young people that look like themselves and see that they aren’t alone in their journey towards engineering,” Coleman said.

The second annual competition will take place May 1, and students said they were already excited to participate.

“Last year, I got eighth place, and they gave me a gift card,” seventh grader Sergio Vigil said, adding that he has a new goal for this year: top three.

Vigil, who is 12 years old, was referred to the Project SYNCERE class by his former STEM teacher at Southeast, Mr. Brooks.

“He asked me if I wanted to be in it, and I said ‘yeah,'” said Vigil, who is thinking of becoming a mechanical engineer because of the class. He said the Project SYNCERE class structure has also made him a better communicator when it comes to problem solving.

“I like how we can work in groups and we can communicate if we have problems,” Vigil said. “If I work alone [and] have a problem, like I stress over it. … But if I’m working with other people, then I can talk to them about it, and we can help each other out.”

Coleman said a lot of students first joining the program aren’t used to working in teams.

“They’re not used to presenting. They’re not used to [talking] about what they’ve learned and what they could do better,” Coleman said.

“So really just helping students to communicate better, become better problem-solvers, team-players — which is really all the principles that go into engineering,” he said. “Even if a student chooses not to go into engineering in the future, I hope they take away some of those skills.”

Note: This is one of two stories for EdNC based on my recent trip to Chicago.