August 2005 was the start of my 11th year as a high school theatre teacher, and my first year teaching at Watauga High School (WHS). Also my alma mater, WHS already had a storied and well respected reputation for high quality performances. I was excited and anxious and tense — I wasn’t sure if I was ready to lead the program into its next chapter.

On Aug. 29, 2005, along with the rest of the country, I watched in horror as Hurricane Katrina walloped the Gulf Coast. Having lived in New Orleans as a small child, I had a vague connection to the destruction I saw on TV: our home had been near Lake Pontchartrain; I had memories of the French Quarter; my father had taught at the University of New Orleans. I felt immense sorrow and empathy for what Katrina victims were experiencing. I remember thinking, “Katrina has forced them to start over.”

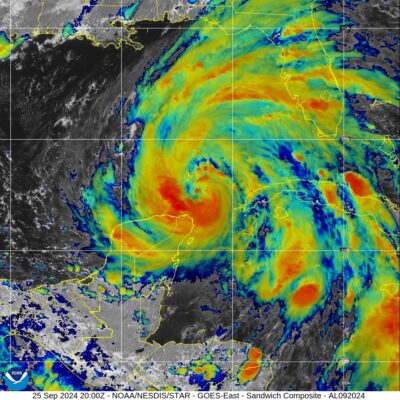

19 years and 28 days later, Hurricane Helene has forced my community to start over.

And, as an educator in my 29th year of teaching, it’s forcing me to start over as a teacher too.

What do you do when 15 days of teaching are gone? From a curricular perspective, from a trauma-informed care perspective, what do you do as an educator?

School districts in western North Carolina are used to missing winter days due to snowstorms and blizzards. Pre-Helene, the most I can remember missing is about one consecutive week.

Even at the start of Covid in March 2020, we missed two weeks with our students before remote learning began.

But 15 days? In a row? For a theatre teacher, that’s two entire performance-skills based units. Or the entirety of time it takes to teach tech theatre light and sound board competencies. Or 15 class play rehearsals.

My theatre teaching co-teacher Zach Walker and I have tried to wrap our heads around this unprecedented loss of in-person teaching time, and we keep asking ourselves what do we take out, what do we skip?

Like many of our colleagues in high school education, we have multiple “preps.” Mr. Walker and I teach five sections of acting classes, four sections of technical theatre, one section of film studies and student directing every single year. The massive undertaking of removing 15 class lessons, from each of those 10 courses, before we see our students in person again, is overwhelming.

I don’t teach math, but I can calculate that every single educator who has been “Helene-d” is rowing in the same boat.

What happens when Mr. Walker and I remove those 15 days from those courses? We’re essentially redesigning our curriculum for each of those 10 classes — for both the fall and spring semesters. Like many high school curricula, our theatre arts curriculum is scaffolded from course to course. Honors Theatre 4 curriculum is predicated on what students know and learned from Honors Theatre 3, which is predicated on what students know and learned from Theatre 2, which is predicated on what students know and learn from Theatre 1.

And — yes, of course — as experienced educators, Mr. Walker and I already differentiate our curriculum daily to support accelerated learning or review-repeat learning for our students.

But this kind of redesign in the compressed timeframe we have is unprecedented. We learned one week ahead of time when our students would return, which reflects Herculean work on the part of our superintendent and her team. We have three teacher work days to prepare for our students, a blessing considering so many of our teaching colleagues can’t get into their schools, much less their classrooms.

Working on these imperative curricular redesigns wasn’t on my radar until we learned our return-to-learn plan. An extraordinary amount of educators in my district dedicated themselves to post-Helene volunteering. In addition to digging out their homes. In addition to chain-sawing their way to homes of friends and families. In addition to finding clean water and places to shower and do laundry.

In 2024, educators are so much more informed on how traumatic experiences affect our students’ ability to learn. But what do you do when an entire school, an entire district, an entire region has experienced trauma?

The cataclysmic, near-apocalyptic damage caused by Helene has traumatized every single person in every single community Helene hit. Everyone knows someone whose road is gone, whose home is gone, whose business is gone.

“Oh, it’s just like COVID times,” non-mountain folks have said to me. No. No, it’s not one bit like COVID. During COVID, we had internet, we had water, we had power. We could see each other on Google meets or Zooms. We could connect to each other via phone and text and video calls.

We didn’t watch a river take our driveway out in real time from our front porch or doom scroll the drone footage of the destruction in Chimney Rock over and over again. We weren’t worried about mold creeping up through the drywall from our flooded basement or wonder when or if we could get a hot meal. Rare is the teacher — or student services counselor or social worker or principal — who has experienced anything close to the disaster heaped on us by Helene. No trauma-informed training we’ve received could have prepared us for the magnitude of trauma that now surrounds us.

Mr. Walker often says to our students, “go before you’re ready.” And that’s what our mountain communities and educational colleagues are doing — we’re going before we’re ready.

We’ll help our students, as we do. We’ll work with and for each other, as we do. We are excited and anxious and tense, yet we stand ready to lead each other and our students.

Because it’s that energy IN a classroom, that synergy of educational “oomph” that gives educators the creative bursts and curricular inspiration that will be required to make up our 15 days.