As anyone who has ever read Goodnight Moon to a toddler knows, shared reading is a magical activity. It helps develop strong parent-child bonds, builds resiliency, and buffers toxic stress in children and families. According to a policy statement, “The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health,” released July 29 by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), experiences with racism in society can be a factor of stress in children and their families.

The AAP, an organization of 67,000 pediatricians founded in 1930, periodically releases policy statements addressing child well-being. It has taken bold steps in the past decade to connect the dots between child poverty and health.

The AAP’s latest report, however, is the first ever to explicitly call out racism. And here is the good news: There are some simple, actionable things that health care professionals — and all of us — can do to address this challenge, starting with books.

In their statement, the AAP explains that “the stress generated by experiences of racism … transforms how the brain and body respond to stress, resulting in short- and long-term health impacts on achievement and mental and physical health.”

The statement makes recommendations for pediatricians and other pediatric health professionals to proactively engage in strategies to make the doctor’s office a safe and welcoming space for all families. Among the AAP’s recommendations is to integrate early childhood literacy programs into pediatric medical homes to “ensure that there is a representation of authors, images, and stories that reflect the cultural diversity of children served in pediatric practice.”

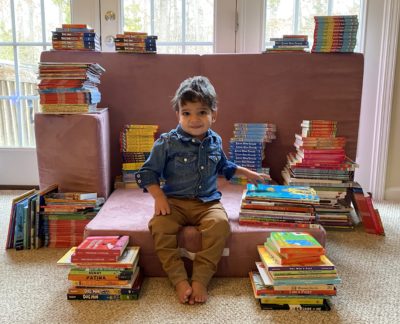

In Durham and across North Carolina, Book Harvest and Reach Out and Read Carolinas (RORC) are working with families through their medical home to support parents and caregivers in making books part of a healthy routine. RORC and Book Harvest together build warm, welcoming, literacy-rich waiting rooms and enable children and families to leave the doctor’s office with armloads of books that will spark shared reading time at home. But those armloads should not be just any books, as the AAP so wisely notes; they must be books that reflect the diversity of our community and that affirm the identity of the child.

The unique trust that parents have in their health care providers makes it imperative that we get this right. The stories that families come away from their doctor’s appointment with can combat the stress, including racism, that can take its toll on children every day and build resilience in families.

Books should serve as mirrors and windows for all children: in order reap the full benefits of lifelong literacy — including the health benefits outlined by the AAP, such as the reduced risk of heart disease, diabetes, and depression later in life associated with mitigating the impact of racism — children have to see both themselves and worlds beyond their own in the stories they read.

Anyone who has ever read Goodnight Moon to a rapt toddler knows that children ask their caregivers to share their favorite books over and over again. We see it firsthand in our work: even very young children prefer books in which they see pictures and hear stories that resemble themselves and their lives.

Children’s books — even books for the youngest babies — can combat racism and its effects on children by serving as windows into our diverse world and as mirrors that provide an affirmation of who they are. That the simple act of snuggling with a caregiver and sharing stories that reflect cultural diversity can yield better health outcomes for our children is a compelling story that we all need to be telling.