Note: This piece is co-written by Jennifer Mann, a North Carolina educator, and one of her former students, Mary Thuma. Mary wrote the first section on her story, and Jennifer wrote the remaining sections.

The story

I grew up watching my mother sew; she made clothes for my family and for others in my village. Just as my grandfather taught her to sew, my mother taught me to sew, and I learned how to stitch a straight line when I was just 5 years old. Though life has not been a straight line, sewing has been my constant.

I grew up in Burma in the time of military corruption and much violence. My father was arrested in the middle of the night. When the military let him go the next morning, he had no choice but to flee, and my family did not see him for a year. When he came back for us, he did so undercover, paying someone to take my family to another village.

It was 2003, and I was just 6 years old as my father, mother, brother, sister, and I set out on a multi-month, dangerous, and physically and emotionally difficult journey to the Karenni Refugee Camp in Thailand. With just the clothes on our back and a few spare sets we carried, we only had each other.

My family lived in refugee camps for seven years. Negotiating with those who controlled the Thai refugee camps and trying to figure out immigration policies was hard on my father. But he persisted, and in 2010, we were approved to come to the United States.

When I first arrived here, I did not speak any English, but I was a teenager, so the school system placed me in the ninth grade. I started school and all I could say was, “Hi. My name is Mary. I don’t speak English.”

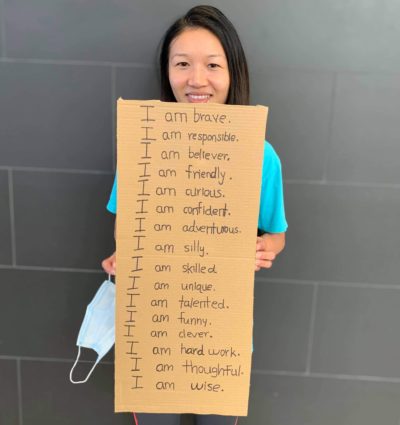

Now, 10 years later, I am working on my bachelor’s degree in fashion design, and I dream of owning a fabric company and providing jobs for women in Asia. There are many woman being sold into human trafficking. Because they are poor, they are desperate and vulnerable.

I want to provide a safe workplace for them to do meaningful work. I dream of helping hundreds of other women. I want to give them an opportunity for success, like the opportunity for success that was given to me. My life has not been stitched in a straight line, but it has been a beautiful fabric of experience.

The power of storytelling

Many cultures believe storytelling is important for community kinship, cultural preservation, and instilling values. Mary’s Karenni culture esteems sharing stories for all those reasons. Storytelling is deemed especially significant within critical race theory, as is the powerful use of counter-storytelling, which is best understood as a method for telling the stories of those who are often not given an opportunity to be heard. Each day I enter my classroom, I am granted the chance to amplify counter-stories and empower and be inspired by young people like Mary.

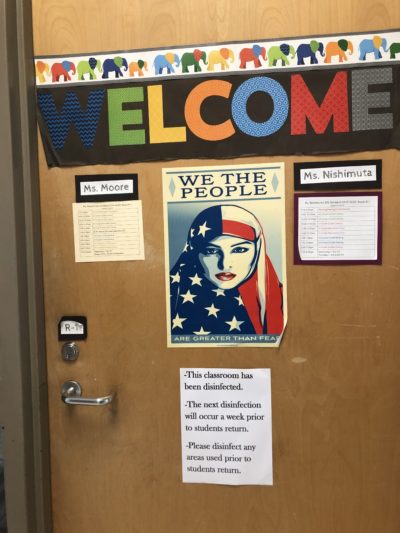

I view my classroom as a community of collective strength and experience. As a North Carolina public school educator for the past 12 years, I have had the opportunity to create an environment which invites everyone to participate in the metaphorical writing of our classroom narrative.

America’s dominant narrative has not given enough space to immigrants and refugees, instead choosing to push them to the margins. Only when everyone can have a voice in writing this nation’s narrative can the true story be heard. Counternarratives like Mary’s need to be told.

The beauty of difference

For more than a century, people have touted America as the melting pot where a multitude of cultures all liquify into one united and uniform culture. The melting pot metaphor is ideal for explaining the concept of a dominant narrative.

New immigrants and refugees are expected to arrive and assimilate, conforming to what they see around themselves. If they attempt to maintain their identity, they are often seen as resistant. If they continue to retain their form and refuse to be melded, they are cast as “other.” Lack of uniformity is not problematic — Mary’s story reveals the beauty and power of difference.

As an educator, the way I view my students is critical and is ultimately reflected in my actions. I seek to provide an opportunity for everyone to learn from each other’s lives and benefit from each other’s assets. My students’ lived experiences are valuable and worth being heard.

Community cultural wealth

I have always sought to amplify the voices of my marginalized students so that my classroom could function as a community of collective strength and experience. Immigrants and refugees in America possess incredible community cultural wealth.

Community cultural wealth (CCW) is an idea that comes from Dr. Tara Yosso in which she seeks to dismantle the concept that some communities are culturally wealthy, while others are culturally impoverished. CCW is an umbrella term, encompassing at least six forms of capital — aspirational, linguistic, familial, social, navigational, and resistant capital. CCW requires the rejection of deficit-based perspectives of marginalized students and instead views them through an asset-based lens, which acknowledges their multiple forms of capital.

Mary’s community is culturally wealthy, and there is much to be learned from her and her story. As educators, we need only to step aside and let our students tell the stories of their lives, which have been stitched by threads of strength and experience.