The following is part of my monthly column, One Day and One Goal: Expanding opportunity in N.C. I invite you to follow along as I share stories from classrooms and explore critical issues facing education in our state. Go here for past columns.

During a recent school board meeting for Guilford County Schools (GCS), American Indian Education Coordinator Stephen Bell introduced himself with a mixture of appreciation and chagrin.

“To be honest, I didn’t really want to speak tonight,” he began. “I should be at culture class with our kids.”

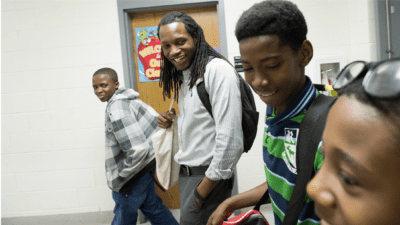

Stephen went on to explain that culture class — “where students, families, and community members come together each week” — is a space held weekly to support students, as well as the broader Native American community in Guilford County.

“Students are there to socialize and learn about our history and culture. Families come together to discuss big plans or participate in talking circles. Community members are there to share their knowledge with the next generation,” Stephen said. “It’s a healing sight to see. [That’s why] I really didn’t want to speak tonight.”

However, Stephen absented himself from Tuesday night culture class in order to call attention to Native American Heritage Month and remind the school board of the impact of GCS’ Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI).

According to the Department of Public Instruction, the total enrollment of American Indian and/or Alaskan Native students totaled 15,953 in the 2020-21 academic year. A bright spot is that over 80% of those students are enrolled in school districts like GCS that receive funding provided through the Title VI Indian Education Act of 1972. However, that means that nearly 3,000 students were in districts without this funding, and this number as a whole does not demonstrate the learning loss and spike in dropout rates symptomatic of the pandemic.

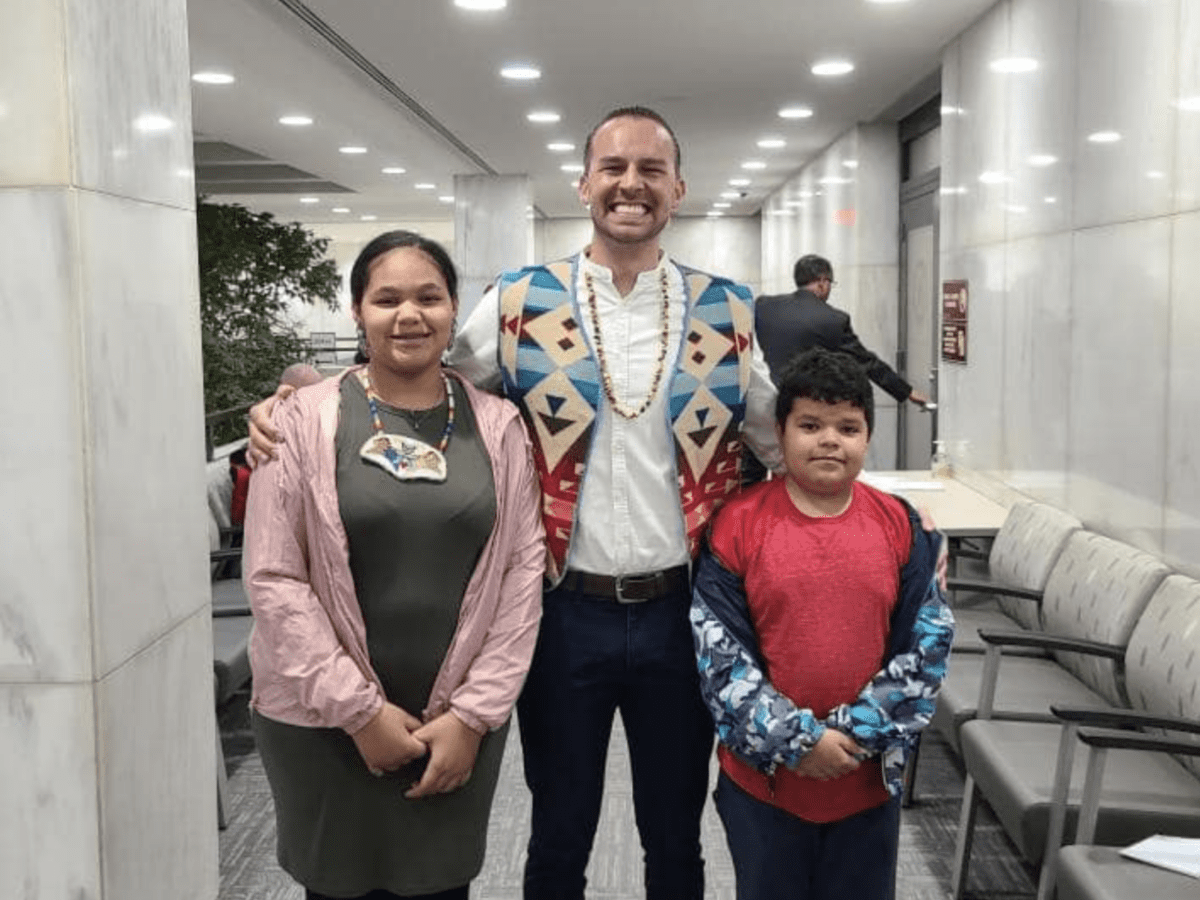

Accompanying Stephen at the school board meeting were GCS students Aiyana and Philip, who echoed his appreciation and request for continued support with personal statements about their experiences as Native American students.

“The Indian Education program has really helped me heal myself and understand that not everyone is going to like me,” shared 14-year-old Aiyana with vulnerability. “I also understand more about my culture and realize that there are other people who can support me besides people at school, like teachers and such.”

Fifth-grade student Phillip followed, saying, “The Indian Education program has helped me learn and share more about my culture [with] people that don’t understand it or think things that are untrue. We have a culture that is important too.”

An invisible history of struggle and support

Stephen Bell was born and raised in North Carolina and is a member of the Lumbee Tribe. However, when he joined Teach For America after graduating from N.C. State University, he chose to teach in Tulsa because of the opportunity it would afford him to work among different Native urban populations. While there, he developed an interest in school-based social work and joined the Kathryn M. Buder Center for American Indian Studies at Washington University to continue his studies. He went on to work with diverse Native communities across the country and took a position with GCS’ DEI Office in 2020, not long after returning to North Carolina.

Since then, he’s lost count of how many times his role is a source of surprise, even when meeting people who also work in GCS. In fact, during his address to the school board, he said honestly, “I’m tired of being asked, ‘How long has your program been around? We’ve never heard of it,’ even though it’s been around since the 1970s.”

I can only imagine how humbled many in the audience felt by Stephen’s statement. I myself hadn’t known the decades of work performed by the GCS DEI Office in support of Native students and beyond; nor did I know that, considering North Carolina’s significant Native population, many more districts are eligible for such funded programs, since the requirement is simply enrolling 10 or more Native students.

Yet, therein lies the problem. The American Indian Education program is just one example of federally-funded, localized responses to the systemic issue of significantly high Native dropout rates. The rates in North Carolina, which spiked as high as 95% in the 1960s and 70s, are not unusual when compared to national averages.

Connected to dropout rates are a number of other alarming trends, as Stephen reminded the school board in his address.

“In North Carolina, Native youth have the highest rates of suicide, the highest rates of EC referrals, and one of the highest rates of being placed in a separate setting,” he shared. “In GCS, our Native students have the highest amount of lost seat time when it comes to behavior referrals and perform consistently low on our EOGs.”

Stephen also called out one invisible cause of such trends by saying, “I’m tired of hearing that one of our students was told they don’t look like a real Indian or being told, ‘You can’t be Native, we killed you all off.’”

When seen in this light, spaces like culture class seem even more important to sustain students through the harsh realities of bullying and other discriminatory practices prevalent in their daily school lives. The American Indian Education program also supports students through summer programming and college and career preparation, as well as outside of traditional educational spaces with dinners, counseling, mentoring, family advocacy, and home visits. These offerings are expanding all the time, yet one of the most critical levers in the experience of Native students continues to be the educators who work with them day in and day out.

Better together

For all of the impact the GCS’ DEI Office has made, including seeing dropout rates drop close to 60% before the height of the pandemic, its history makes clear that all of the resources and curricula in the world will not be enough to undo the decades of racism and discrimination that Native students have endured. More accurately, there are centuries’ worth of systemic issues and side effects that require our allied care and effort in order to address.

As Stephen so eloquently put it, “If I know and believe in [GCS Superintendent] Dr. Oakley’s vision of ‘Better Together,’ I can’t do this alone.”

“‘Better Together’ has looked like preparing staff with resources and training focused on Native identity and culture. It has looked like partnering with student support staff across our district to provide academic or mental health support for our kids at risk. It has looked like partnering with Western Middle School to hold our very first summer culture camp this year or being invited by GCS to share our culture and knowledge, to ensure all kids can understand that Native people were not all killed off. That we are still here.”

“‘Better Together’ looks like everyone using their voice to advocate for Native kids. ‘Better Together’ means that our native kids are more than just statistics. They’re our future doctors, football and volleyball players, chefs and artists, welders and business owners. ‘Better Together’ understands that our Native families don’t just carry intergenerational trauma. They carry intergenerational strength and wisdom.”

“‘Better Together’ means that what we do today impacts the next seven generations, and ‘Better Together’ ensures that our district’s vision of transforming learning and life outcomes for all children includes the original Southerners — our Native children — as well.”

“I invite you all to not just believe that we are better together but also take action, knowing that Native communities have always and will always exemplify ‘Better Together.’”