Listening to our students about their struggles is a vital part of being an educator. This empathy is particularly important when your students identify with traditionally marginalized communities, such as the LGBTQ+ community.

Teachers are essential advocates for LGBTQ+ students. They are important resources for students seeking connections and support, they can sponsor gay-straight alliances, and they can discuss bullying based on sexual orientation, just to name a few.

The other way educators can advocate is by lifting up the voices of their LGBTQ+ students. As the voices of these students are frequently unheard, this article is a collaboration of work with LGBTQ+ students from within the North Carolina public school system who represent an intersection of experiences and identities.

As one student notes, “Being a Black, queer, teenage woman has been a label that has branded my back all throughout my high school career. Because of my personal situation of not being out to my family, having support within the education system becomes a lot more essential.”

The necessity of advocacy

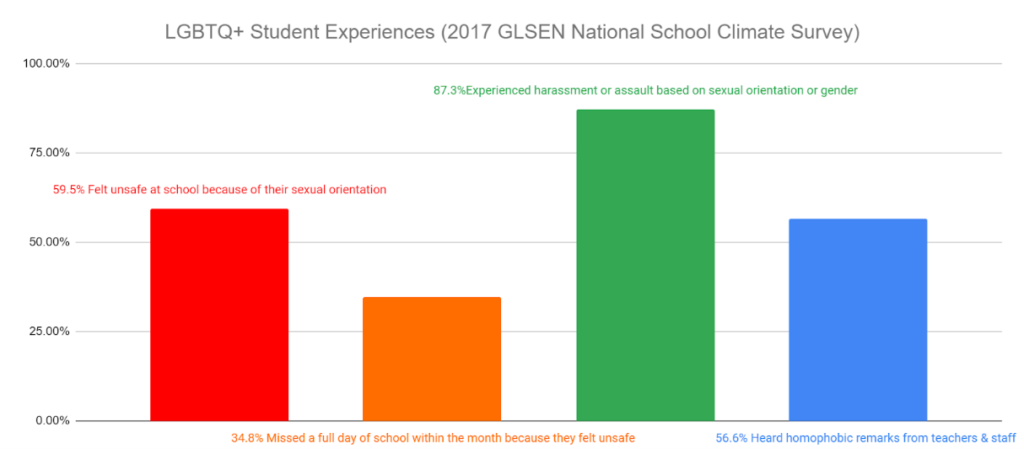

While a common public perspective holds that schools in the United States are increasingly accepting of gender and sexual minorities, data shows that schools and society are still not safe for LGBTQ+ students, teachers, and their allies. The current political climate, a lack of school-level visible allyship, and a lack of LGBTQ+ topics in curricula all create a culture ripe with bullying and explain the disconnect many LGBTQ+ students feel. Responses to the COVID-19 epidemic exacerbates many of the issues facing these students.

In schools, bullying continues to disproportionately impact LGBTQ+ students as compared to their heterosexual peers. With regards to school safety, the 2017 GLSEN National Climate Survey shows that the vast majority of LGBTQ+ students do not feel safe or supported in schools.

Sadly, not all schools and teachers support LGBTQ+ students. As one student notes, “At my previous school, fellow students teased me for my sexuality despite never officially coming out. Their harsh words and belittlement made coming to terms with myself and my sexuality incredibly difficult. For high school, I switched to a new school and found a welcoming community. My peers and teachers welcomed and accepted me as I was, and I learned I deserve to be loved and to love myself.”

GLSEN’s research supports this story, showing that 55.3% of LGBTQ students harassed at school do not report the events to school staff, citing that they think the situation will get worse and their doubts that effective support will take place. LGBTQ+ representation, even at the high school level, is lacking. Less than a quarter of teachers surveyed mentioned LGBTQ issues even once annually in their curriculum, and many states have explicit bans on mentioning anything other than heterosexuality in schools. Although both schools and homes can be tough places for students, teachers can create a supportive environment.

Teacher allyship in action

There are three action steps classroom teachers can take to show their allyship with their LGBTQ+ students.

Provide whole class representation

- Intentionally include LGBTQ+ individuals, issues, and authors in your whole class curriculum. It is a great way to model acceptance and advocate for students. When students see their identities reflected in course readings, they feel more accepted. One junior commented, “I have yet to read a LGBTQ+ book either assigned in a class or promoted by a school through my whole education. Most other groups are represented, but our book diversity lacks any diversity in LGBTQ+ authors or characters.”

- Read texts from the perspectives of others to build empathy. A senior responded, “Everybody should know something about queer history regardless of whether or not they’re a part of the community. I think kids would be more understanding and respectful of the community if they were exposed to LGBTQ+ authors and characters. We’re people.”

Avoid heteronormative groupings

- Manage your personal gender stereotypes and assumptions about student behavior when grouping or organizing students. As one student recalled, “My earliest connection between my identity and school was third grade. I distinctly remember, after playing a game with my classmates that aligned people via gender, I had proudly announced that I was ‘a boy too.’ When returning from recess, my third-grade teacher asked me very straightforwardly: ‘Is that what you want? To be a boy?'”

- Do not misgender students. This is a microaggression that can make them uncomfortable as they then have to refute the teacher, an authority figure, or accept your designation when it is not correct. Ask students confidentially at the start of the year — or even now — how they prefer to be addressed in your class.

Check in with your students

Whether via distance learning or in person, check in on how students are feeling, both informally and as a structured part of class. It can clue you in on if students need support.

As another student reminds us, “Teen years are already enough of a struggle, so don’t make it any worse. Be decent, use correct pronouns, and be kind. Maybe you’ll save a life, or just make someone feel better at the very least.”