The achievement gap is one of the most important challenges in education. We’ve gone through waves of education reform. We’ve spent billions of public and philanthropic dollars. Despite these efforts, we’ve made too little progress in solving this problem.

An alternative view

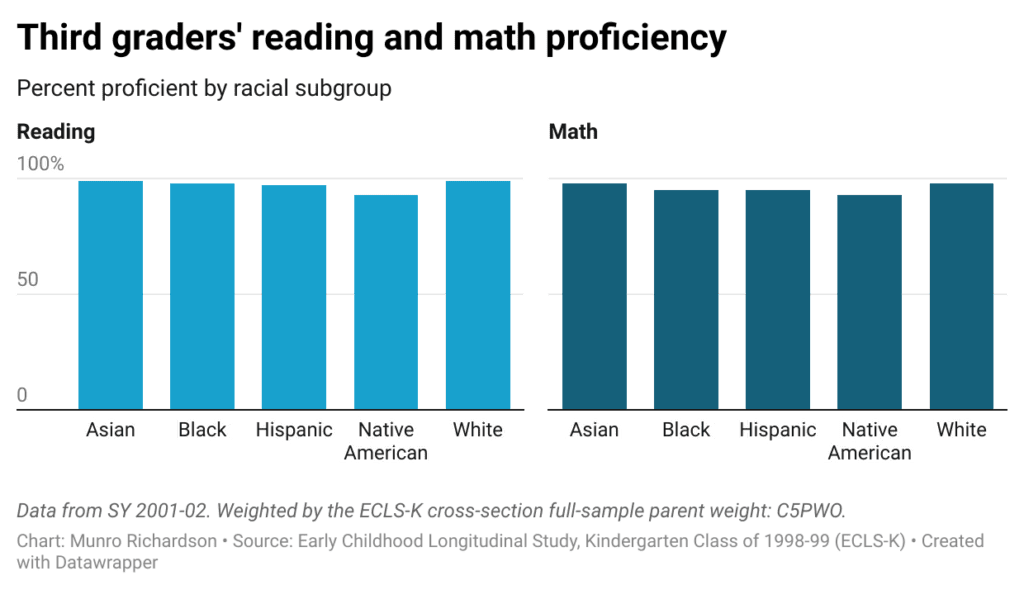

We are so accustomed to dismal education statistics, it might be hard to believe the positive reading and math data in this chart. There is no evidence of a significant achievement gap.

These data are real. They come from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Studies program, a series of multiyear education research studies of nationally representative groups of American children. This particular study followed roughly 22,000 students from kindergarten in fall 1998 through eighth grade in spring 2007. The reading data show third graders’ proficiency with sight words in spring 2002. The math data show their proficiency in addition and subtraction.

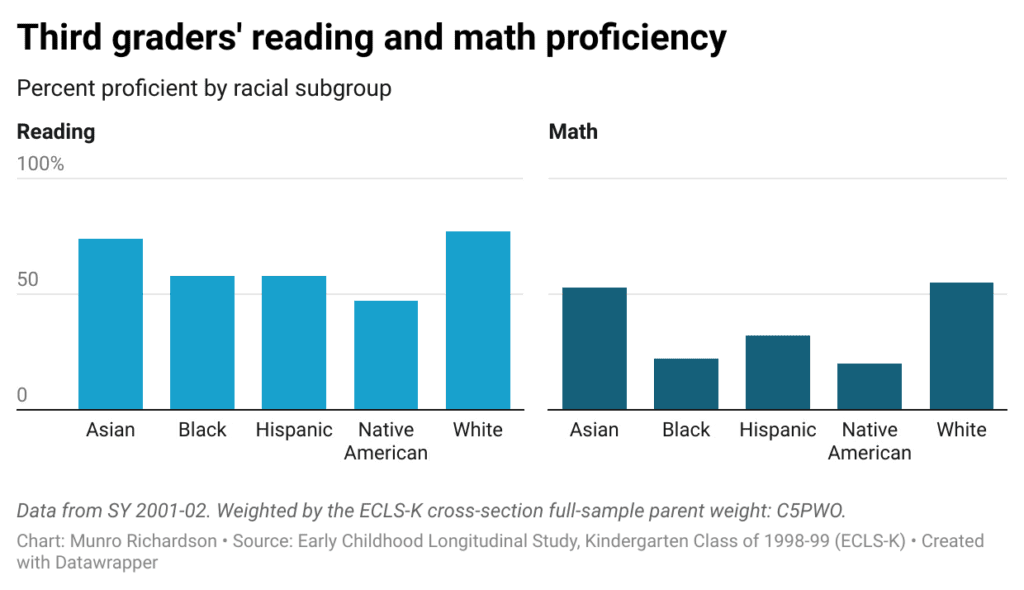

Of course, we expect much more of third graders than sight words and basic math. This next chart shows proficiency for this group of students in a different set of reading and math skills.

This chart looks more familiar. There is a 15 to 30 point gap between Black, Hispanic, and Native American students and white and Asian students. The reading skill is literal inference (comprehension). The math skill is place value of integers to the hundreds place.

This is not just a comparison between “basic” and “complex” skills. The first chart includes examples of constrained skills. The second chart includes examples of unconstrained skills. Both are important but develop differently. Gaps in unconstrained skills heavily drive the achievement gap.

Constrained and unconstrained skills

In 2005, Scott Paris, a former University of Michigan professor, published the first of a series of articles describing two types of reading skills: constrained and unconstrained. Over the next 20 years, other researchers expanded on this constrained skill framework, including adding math and executive skills.

Today, researchers suggest skills differ in four fundamental ways:

- The amount of knowledge or information associated with learning a particular skill.

- The definition of mastery of a skill and whether it’s the same for everyone.

- The amount of time typically needed to reach mastery of a skill.

- The manner in which a skill is learned or acquired.

Constrained skills involve relatively limited amounts of information, e.g., alphabet, word reading, counting, addition, subtraction, etc. Everyone has the same information. Mastery is clearly defined and the same for everyone.

Constrained skills are relatively straightforward to teach and assess. They are mostly learned in classrooms. Explicit and systematic instruction supports learning these skills. Typically developing kids largely master constrained reading and math skills in elementary school. Some children have challenges with reading (dyslexia) and math (dyscalculia). Good systematic instruction can help, particularly if learning differences are diagnosed and addressed early.

Unconstrained skills involve broader amounts of information, e.g., vocabulary, relational thinking, content knowledge, etc. Everyone doesn’t have access to the same information. There is no universal finish line for mastery — and always the opportunity to learn more.

Unconstrained skills tend to develop more slowly than constrained skills. Kids acquire unconstrained skills at different rates and to different levels of ability. It is not as straightforward to teach and assess unconstrained skills. They develop from instruction, experiences, and practice inside and outside of the classroom. Executive skills — working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition control — are also unconstrained and support reading and math achievement.

Greater gaps for unconstrained skills

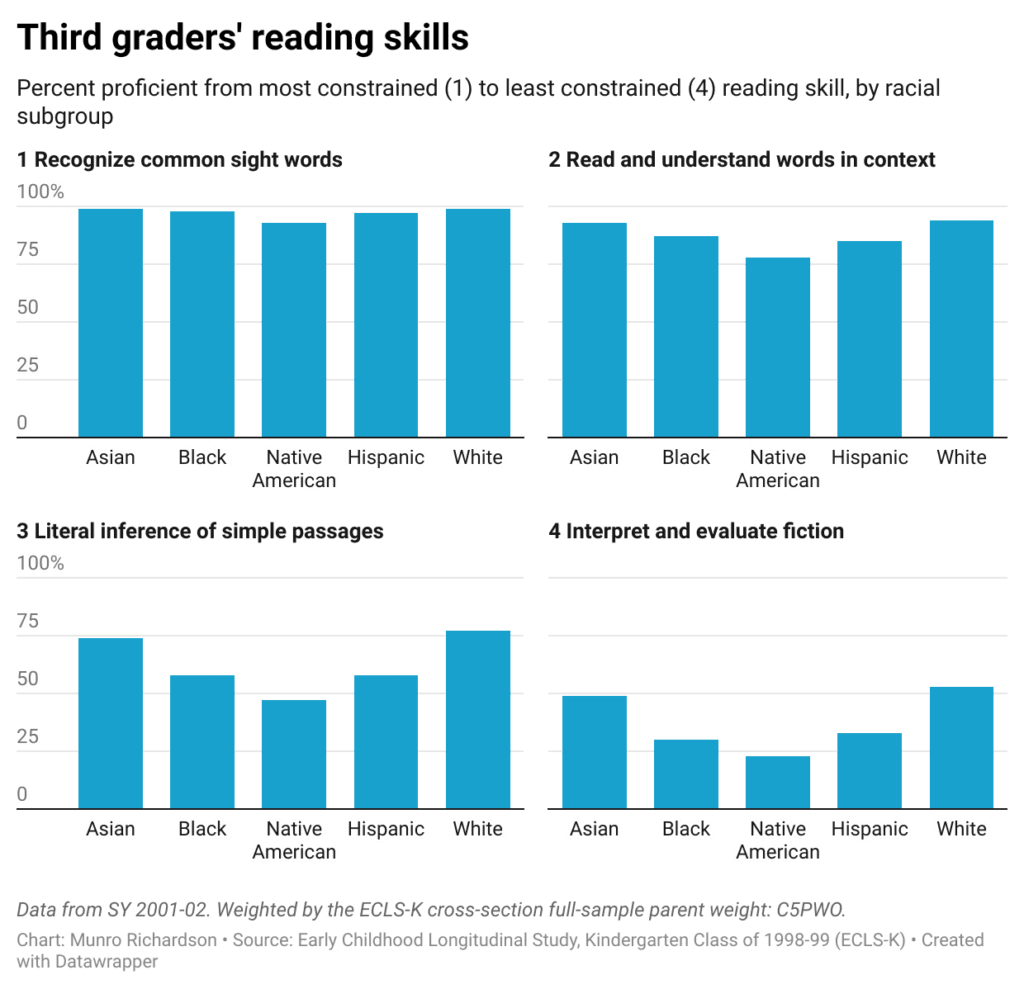

Let’s return to our third graders in 2002. This next chart includes a wider range of reading skills. Skills are ordered from more to less constrained. Overall, we find higher proficiency and smaller differences for more constrained skills. Gaps emerge as skills become less constrained.

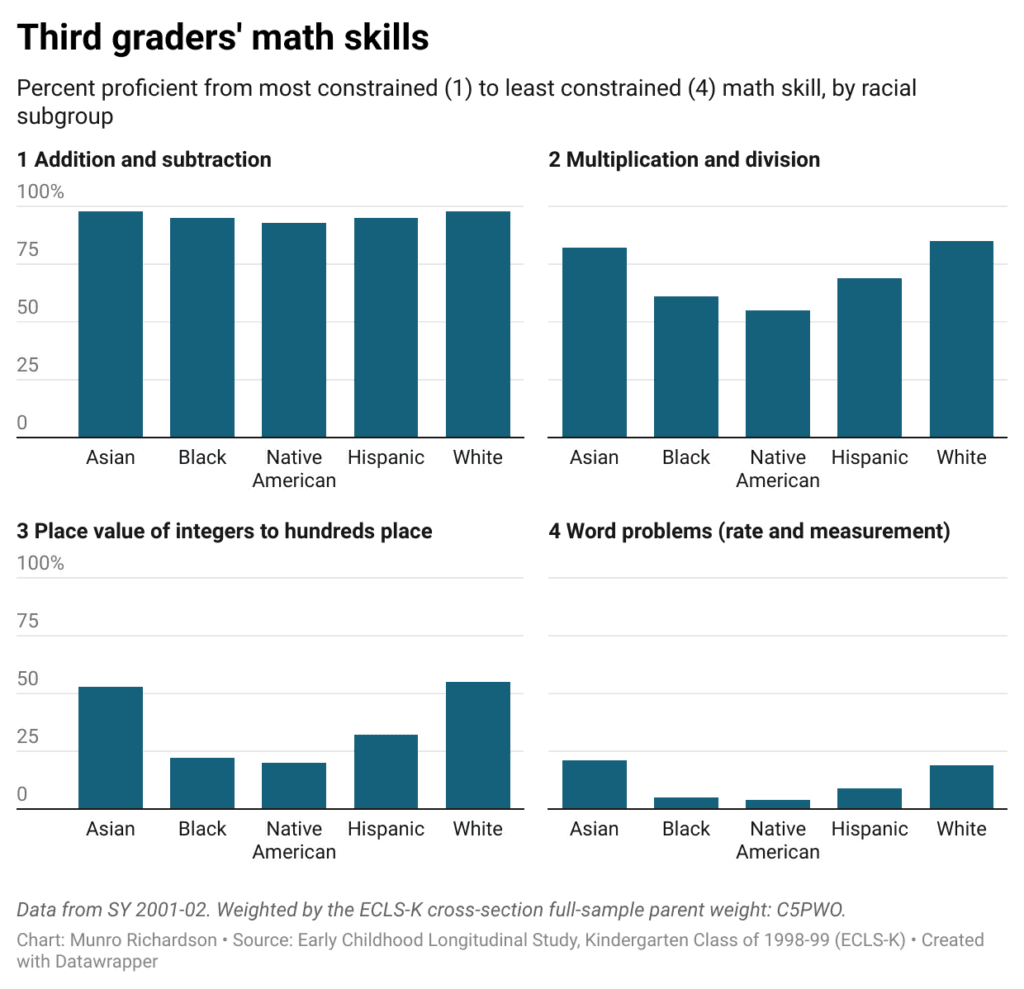

The next chart shows a similar pattern for mathematics. The less constrained the skill, the greater the gaps between groups. Gaps in multiplication and division (a constrained skill) between these students will eventually narrow by the end of middle school. But gaps in unconstrained skills on the bottom row will carry into high school.

A more recent view

This is a 20-year-old view of the achievement gap. A great deal has occurred in American education. Do similar patterns exist today?

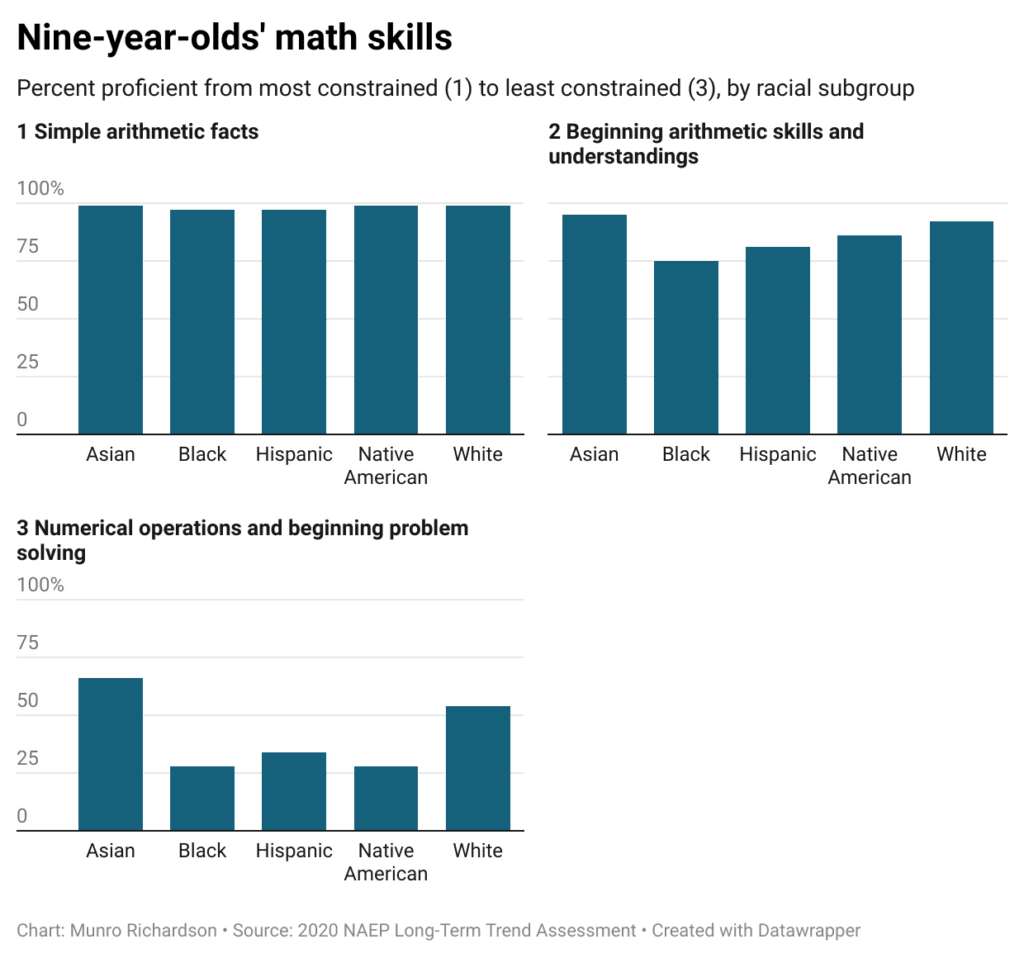

To answer this question, let’s look at math skills of a nationally representative sample of U.S. nine-year-olds in 2020. These data come from the long-term trend version of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. It was administered just before school closures due to the pandemic.

In this next chart, only the first skill — simple arithmetic facts — is constrained. The other two are combinations of constrained and unconstrained skills. (NAEP skill descriptions are available here.) The proficiency patterns of nine-year-olds in 2020 mirror the third graders in 2002. The most significant gaps are in the less constrained skills. An analysis of reading skills yields similar results.

The achievement gap is an opportunity gap

Skills develop through an iterative process. New knowledge is learned and consolidated, and newly acquired skills are integrated with existing skills. Skills are gradually built and transferred through practice in real activities in specific contexts. As Nobel laureate James Heckman puts it, “skills beget skills.” This requires regular, predictable environments and prolonged practice over time.

Children are much more likely to receive similar opportunities to develop constrained reading and math skills than unconstrained skills. To close the achievement gap, we need to close early gaps in constrained skills like word reading and numerical operations. But the far greater challenge is closing gaps in unconstrained skills like vocabulary, relational thinking, and world knowledge. These skills depend upon experiences and practice in formal and informal learning environments. Unconstrained skills are built in the schoolhouse, at home, and in the community.

Researchers for years have called for more focus on unconstrained skills. This is more critical than ever given the decline in reading and math scores in the wake of the pandemic. Closing the achievement gap, and recovering from pandemic learning loss, requires aligning systems inside and outside of schools to provide opportunities for students to build constrained and unconstrained skills.