On one memorable Saturday morning, when I was a rookie reporter in New Orleans, the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a desegregation ruling applied to the city’s public schools. In those pre-email days, I went to the federal courthouse in the French Quarter to pick up the text. There, a law clerk told me that Judge John Minor Wisdom wanted to see me in his chambers.

Wisdom, a Republican appointed to the judiciary by President Eisenhower, had a wide, justified reputation as a courageous Southern judge in enforcing the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board decision. As I approached his desk, he greeted me with a short, blunt sentence: “You’re not here.”

What he meant was that our session was off the record, and that I could not disclose then in print that we had met. In summoning me, Judge Wisdom wanted to ensure that my report in The States-Item, a now-defunct afternoon newspaper, accurately conveyed what he expected of the city as schools opened on the next Monday morning. He guided me through his ruling so that I would get it right — and I appreciated his guidance because I wanted to get it right.

That story, which I have used in teaching students about journalism in the real world, came to mind again as I read Justice Robin E. Hudson’s remarkable opinion for the state Supreme Court’s majority in the Leandro case. No, she did not summon me for an off-the-record briefing. But her lengthy opinion conveys an earnest effort to guide North Carolinians through a long-running, complex case so that the state would at last get it right.

Hudson, whose 15-year service on the high court will end in December, does not issue a decision solely on how much money the state should spend to comply with the constitutional mandate to afford every child the opportunity for a sound basic education. She offers lessons in history, in legislative and judicial powers, and in the societal value of public education.

Tellingly, Hudson positions the Leandro case in the context of the 1954 Brown ruling. As she recognizes, there are differences: Brown dealt with denial of education access, Leandro deals with denial of education adequacy.

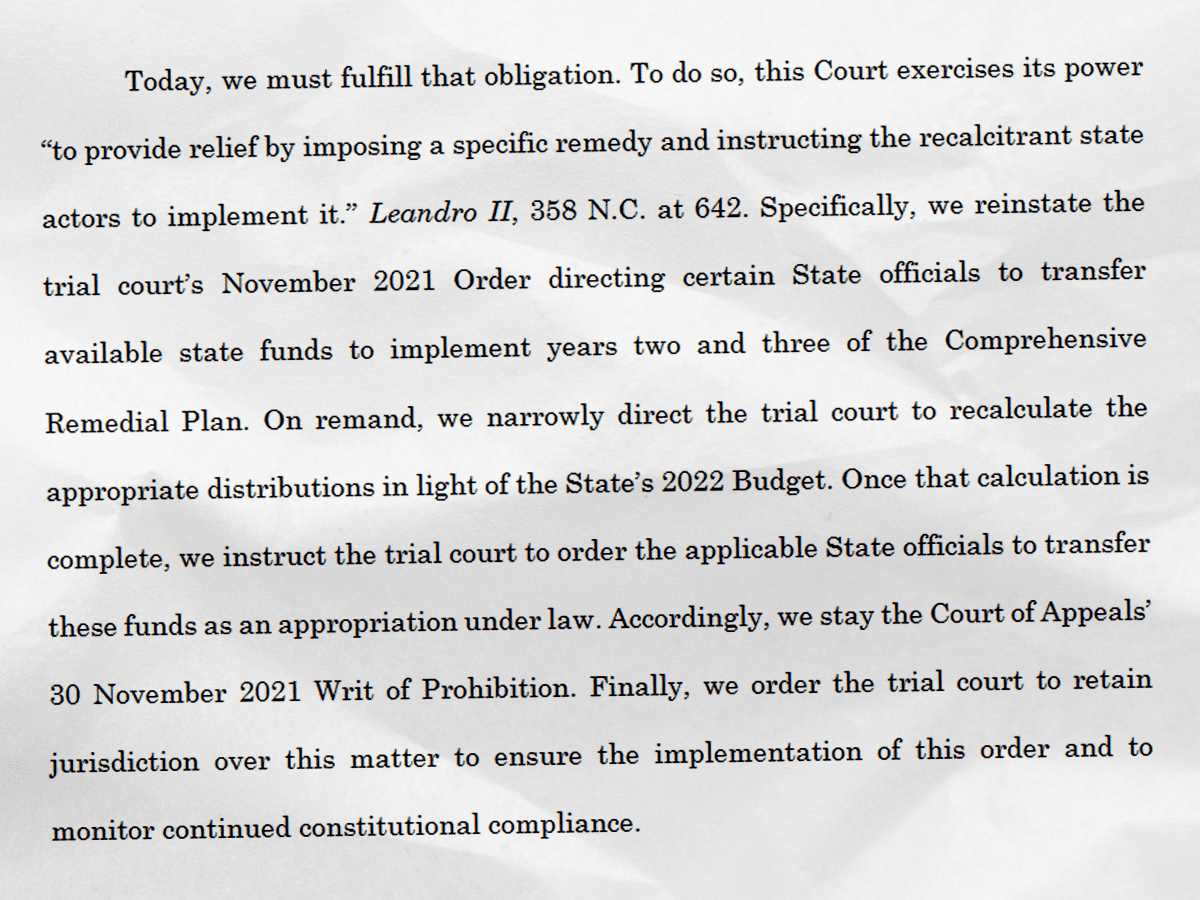

Still, she writes, there exists a “fundamental alignment of the question at the heart of each case: what is the proper role of the judiciary in guarding and maintaining the constitutional rights of marginalized school children in the face of ongoing violations?” Through its 1954 ruling, she writes, the U.S. Supreme Court offered a precedent for a “broad scope of judicial equitable remedial power in protecting the constitutional rights of marginalized students from executive and legislative violation and recalcitrance.”

Hudson also recognizes that the majority’s opinion issued last week is not the “final page” in this case. After all, the state Supreme Court sent the case back to Superior Court for implementation. What’s more, the results of elections this week — with Republicans retaining a solid legislative majority and gaining a new majority on the Supreme Court — set the stage for further legislative and legal contentiousness.

In the General Assembly, Republicans have resisted two-year, pre-K-12 funding to the extent called for in the Comprehensive Remedial Plan, the clunky-worded title of the actions spelled out in the WestEd report that formed the basis for recent court orders. Whether in the legislature or the courts, at issue are not competing plans to be negotiated in quest of a compromise. As Hudson writes, “The CRP is the only remedial plan submitted to the trial court by any party in this case.”

Surely knowing that partisan and legal contentiousness are in store, Hudson’s majority opinion reasserts basic verities and seeks to define the issues more broadly for North Carolinians. The opinion declares that “public education is a public good,” and calls on the parties to the case to “imagine a future in which all North Carolina children receive the opportunity to a sound basic education.”

“When the State ensures that a child has the opportunity to receive a sound basic education, it is not only that child who benefits,” Hudson writes, drawing on earlier language in the case. “It is not only that child’s family that benefits. It is not only that child’s community that benefits. Rather, when a child receives a sound basic education — one that prepares her ‘to participate fully in society as it exist[s] in … her lifetime’ — we all benefit.”

The late Judge John Minor Wisdom whom I met on that Saturday morning back in the day would surely appreciate the effort by a veteran justice to guide her state to get it right.

Recommended reading