Is North Carolina about to take a giant step backward on early literacy? It seems so with the potential adoption of a flimsy definition of quality reading instruction not based on how we know children actually learn to read.

A Department of Public Instruction (DPI) committee is recommending a non-definition, meaningless phrase that could have profoundly negative implications for how teachers teach reading, how they are prepared to teach reading, and what and how much kids learn and develop as readers. This move toward a nothing-definition could undermine the major accomplishments the state has made in the past few years in early literacy. It could mean the difference between North Carolina becoming a national leader in early literacy or the state losing ground in its efforts to ensure all children are able to read well.

Here’s the nothing-definition:

Grounded in the science of reading, high-quality reading instruction is guided by state-adopted standards, evidence-based planning and teaching, and the ongoing monitoring of essential skills and understanding to support the learner in comprehending and engaging with increasingly complex texts.

Why is this a problem? Although the statement contends the definition is “grounded in the science of reading,” it is not. It’s no secret — the science of reading is not just about what needs to be covered, it is also about how it is taught — the pedagogy. That science needs to be fully outlined in the definition so there is no confusion about what constitutes quality reading instruction and what does not.

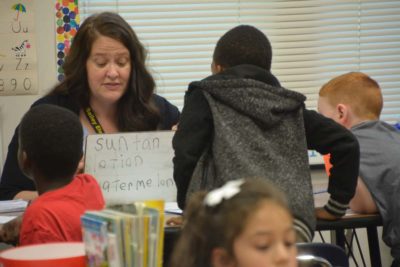

What is missing in this definition is crucial. Barbara Foorman, a renowned scholar of early literacy and a regular consultant for the state, and Monica Campbell, a leader in literacy teacher preparation in the state, have weighed in on this issue in past EdNC articles. Both suggest that the definition name essential components of early literacy instruction such as phonemic awareness and phonics, accurate and efficient word identification, language, and comprehension. They also recommend that the definition name the required pedagogical strategies for the teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics, two foundational skills of early literacy instruction often seen as controversial. Foorman and Campbell say these skills must be taught systematically and explicitly.

We must use the words systematic and explicit in the definition of quality reading instruction because of what might happen if we don’t. Today, across the country, many teachers say they value phonemic awareness and phonics instruction and teach them. But when teachers are observed, instruction on these foundational skills are often “embedded” in a read aloud lesson, a writing lesson, taught from a “word wall,” or other non-systematic, even haphazard lessons.

These common practices, sometimes learned in teacher preparation programs, mean some kids might pick up some sound patterns or sound-symbol correspondences, but many will not. The science of reading shows that when children are taught in a systematic manner in which skills are built on previously learned skills, they acquire and apply those skills.

Many curricula are written to support teachers in doing just that. It is not a huge lift for teachers if they follow a quality program. It is a huge lift for teachers to ensure all kids have a deep understanding of foundational skills such as phonemic awareness and phonics if they teach skills in a hit-or-miss manner, as in the lessons mentioned above.

The teaching of reading must also be explicit. Explicit instruction is when teachers direct or explain something to students, rather than guide or facilitate. Explicit instruction is important for all children when they are learning something new. It is especially important in cases in which the language patterns, or discourse, of the teacher is different than that of the students.

More than 30 years ago, MacArthur-awarding winning educator, Shirley Brice Heath, identified different ways of interacting in homes and classrooms of different cultural groups in the piedmont of North Carolina. She wrote that when teachers used indirect language, many children may not understand and learn from instruction. A few years later, in 1988, another MacArthur award-winner, African American educator Lisa Delpit, drew on Heath’s work to emphasize the value of explicit instruction for black children, especially for literacy instruction.

Delpit had been trained to prepare teachers in an indirect, non-explicit, non-systematic instructional approach. Yet she found that the approach was not supporting all learners and began to observe other approaches, including a phonics-based reading program. She watched as all the children learned to read in the direct, explicit, systematic approach, including the African American children she keenly observed. Delpit wrote:

“The explicit phonics program was successful because it actually taught new information to children who had not acquired it at home (1988, p. 286).”

Delpit explained that she does not advocate a basic skills-only approach, but she does suggest that all children need explicit teaching when learning skills that are new to them, and teachers can find ways to do that in any classroom. The field of early literacy has largely come to consensus that the foundational skills of early reading are not learned “naturally” as some used to think, and that unless skills are taught explicitly and built on previously learned skills, many children will not learn what they need to become fully proficient readers.

In North Carolina, many efforts have been undertaken in the past several years to reckon with current research on how children learn to read and how to best teach them. From 2013 to 2020, I had been part of many of these efforts and have been heartened by a coalescence of understandings and practices around the science of reading.

This growing consensus happens when we say clearly — explicitly — what is meant by quality reading instruction. It is no time to back away from the details of the definition. It is time to double down on policies and practices that will ensure teachers are supported in learning the science of reading so children in North Carolina become the literate citizens the state needs.