Daykota lives in a camper with his family, maintains an A average in English, and has no access to the internet. Shawn lives in a trailer with three generations of his family, is the best writer in school, maintains an A average in all classes, and has no access to the internet. Tayana works at KFC to help support her one-year-old, maintains an A average in English, and has no computer. Lindsay is an exceptional needs student, maintains a C average overall, and has no access to cell service or the internet.

These stories of our students go on and on as the reality of our state’s inequities begin to hit our most vulnerable children literally where they live. And while North Carolina’s educators can give voice to these needs, it is only those with the power of legislation who can create the change for which we advocate.

And it isn’t just equal broadband access that families across the state need. We know that education and communication don’t even appear on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and we know that everyone first needs adequate nourishment, decent housing, and free or affordable health care in order to survive.

It seems absurd to say that we cannot educate our students equitably without giving them all access to the internet when we also know that it is those same students who, for their entire lives, have not had regular meals, shelter, hygiene, or health checks. The fact is, however, it took COVID-19 to remind all of us that lack of access to the internet is just the tip of the iceberg of inequality experienced by one out of five children who live in poverty.

If compassion is not enough reason to do whatever it takes to address and amend these absolute wrongs, then let’s take a look at economics. It seems like common sense, but numerous studies support the positive correlation — financial and otherwise — of economic security and improved outcomes for children. According to those studies, providing basic needs to children, again and again, means improved self-reliance when they reach adulthood.

But for education purposes, basic needs are where we start, not where we end. In this strange period of COVID-19, the only way to begin leveling the playing field for public school children is to offer every student safe, regular, and reliable channels of learning to replace the safe, regular, and reliable classroom communities that the best public school teachers have always worked to provide.

The two of us are among the thousands of teachers who understand the significance to the future of giving children every chance at success that we can afford. From our personal experiences growing up as well as from our combined fifty years of teaching, we know it is impossible to overestimate the power of opportunity.

Chad Beam, Cleveland County Schools

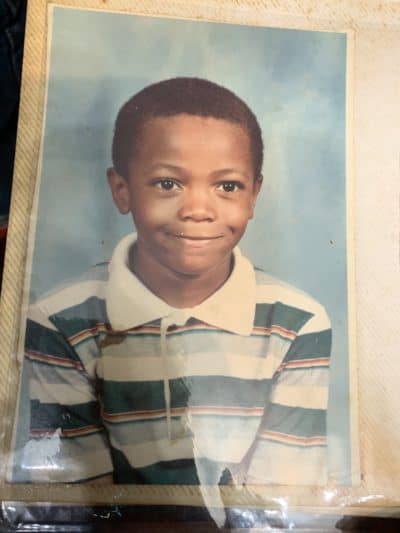

Combine the gross multi-generational poverty attributed to high school-dropout-ancestors-turned-cotton-pickers-and-furniture-factory-workers with the likes of an innocent, adolescent African American boy, frustrated, ridiculed, and labeled “slow” due to an unidentified learning disability, and what do you get: an English teacher who has been Teacher of the Year at two different schools, twice for the same county, and who currently serves as North Carolina’s Southwest Regional Teacher of the Year.

It was not free internet access that leveled the playing field. It was not a one-to-one initiative that broke the curse of poverty and an anger-laden disenchantment with learning. It was not a “hot spot” that saved me from the frigid fixtures of failure that drowned my younger brother, caused my younger sister to drop out of high school in the 10th grade, and ferociously sought to claim me.

It was, instead, the focused love of educators who saw beyond the holes in my shoes, the smell of my jeans, and the rat-infested three-room shack I stood in front of at the bus stop. It was in the eyes of compassionate educators that I first saw the beacon of hope. Through those lenses, I caught glimpses of my own potential, and I saw what they saw: something bigger than the blight of being broke and the belittling label of “at-risk.”

When the pandemic of an unknown disability — now called dyslexia — sought to destroy my hopes, it was the equal opportunities, rooted and grounded in the love of passionate educators who met my basic needs, that gave way to the recognition and actualizing of my God-given potential. This love and provision shattered any inequities I faced. Any titles and awards I’ve been blessed to receive as an educator have initiated in me a deep desire for reciprocity: to provide that same love and provision of basic needs, not just in my classroom, but to students at large.

Dawn Gilchrist, Jackson County Schools

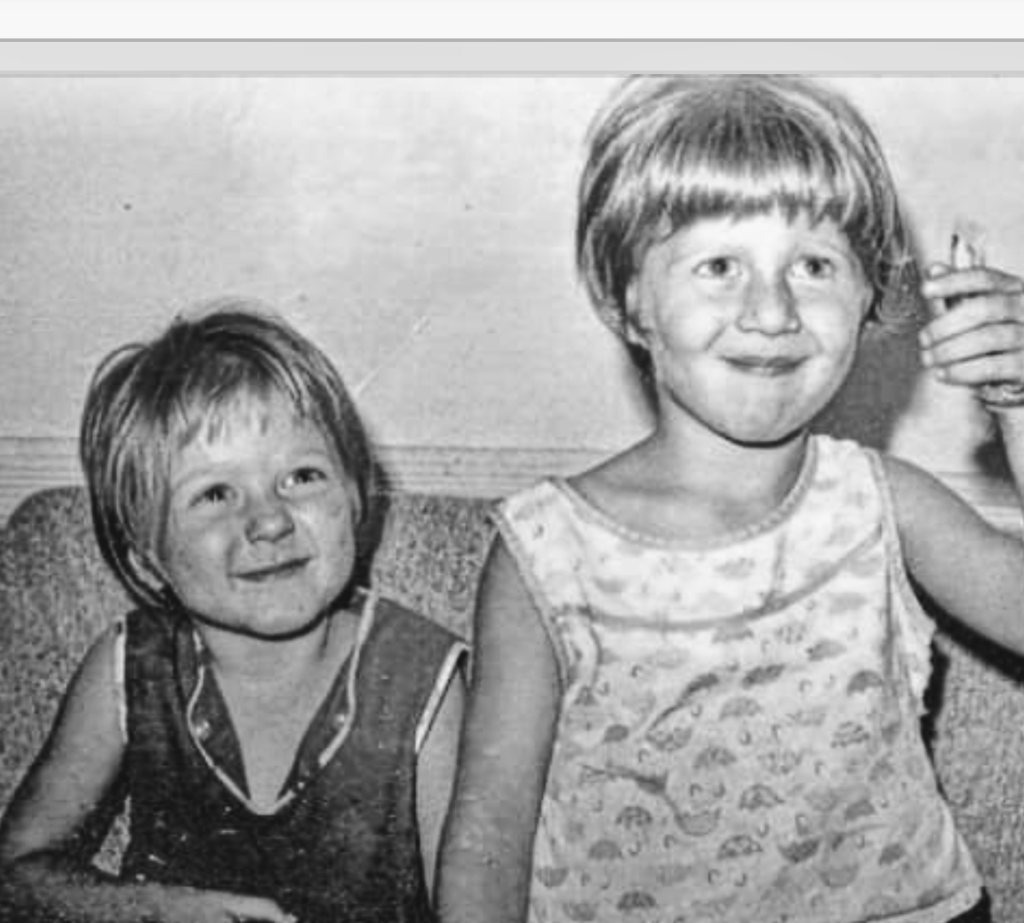

My upbringing was in many ways like that of my students. My family lived in a trailer on the side of a mountain, and it was crowded with seven of us, although my father added a few rooms as he could afford it. My parents both earned their GEDs, Dad in the U.S. Army, Mom when she was 40 at a community college.

They emphasized self-sufficiency — my father was a stonemason, and we had two gardens and livestock, so they worked from “can see to can’t see.” Besides giving us the gift of a work ethic, my parents somehow had the wherewithal to fill our single wide trailer with books, everything from a collection of literary classics to Westerns and mystery novels. Their wisdom during those formative years gave my siblings and me what studies have now borne out: words, and lots of them, are the best contribution a parent can make to their children’s success in school.

When Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty” brought Head Start to Swain County, all of the Gilchrist children were on that bus, scrubbed in the small bathtub, fed with home canned vegetables, and ready to see what the world had to offer. We five are now among the numerous successful adults who received the benefits of compassionate legislation that became preschool intervention.

The legacy of my parents and Head Start, for me, has been the completion of three degrees and a lifetime of dedication to public schools. The awards I received as an undergraduate at Western Carolina University became a full ride through graduate school at Columbia University, and those translated into an MFA in Writing at Warren Wilson College — the gains of which I can now offer every student I teach. The opportunities I had, first as a result of two people determined that their children would become good human beings, and second as a result of legislative foresight, have compelled me to continue the trend that my parents began.

Last week, our schools began sending home “packets” to our many students without broadband access. Many were delivered by bus, along with meals. Others were mailed. The packets include everything from books on CD to novels to worksheets for documenting earth science experiments. The packets also include encouraging notes from teachers to individual students.

The fact remains, however, that a packet is not animated, nor does it have a human face. A paper packet is to remote learning what a one-dimensional picture of a classroom is to a vibrant space full of children: there’s no comparison. Sending our children packets may be the best we can do in the circumstances in which we currently find ourselves, but the inequality is blindingly obvious, and shame is just not enough.

If we cannot do better for our children, we deserve the dire outcomes that are predicted. Our children, however, do not.