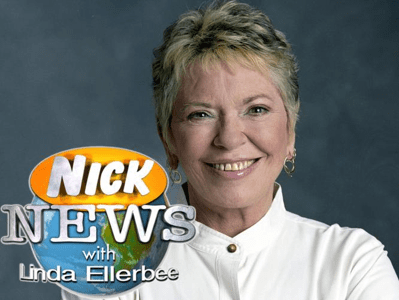

Growing up, one of my favorite shows was Nick News with Linda Ellerbee. For those who missed it, Nick News was a long-running news show for kids hosted by Peabody-award winning journalist Linda Ellerbee.

Early seasons of the show explored myriad topics framed by the “Five W’s” (Who?, What?, When?, Where?, Why?) and the occasional 6th, How?

I didn’t realize in the early-90s how much Ellerbee’s approach would impact my future work.

A few weeks ago, the Belk Foundation hosted a series of sessions under the banner “North Carolina and the Science of Reading.” We brought in national presenters to speak about how Mississippi had an unprecedented boost in fourth grade reading scores, why we need to focus as much on content knowledge as foundational skills, and how to support teachers in bridging the “research to practice” divide.

In my opening remarks, I referenced the resurgence of the “reading wars” playing out in my Twitter feed. I asked the attendees to remember why there’s so much passion in reading. We all know how important it is, but in 2019, only 45.2% of North Carolina third graders were reading at College & Career Ready levels. Keeping the reading wars in mind, I urged attendees to take off their “team stripes” and listen to the presentations with curious ears.

I’m watching (and admittedly, participating) in a precarious tug-of-war playing out in early reading discussions right now. In our collective outrage about our nation’s dismal reading proficiency, we are picking sides and digging in. Over my decade of education philanthropy, I’ve never seen the term “salvo” used so often to describe competing educational practices.

Why is this happening? In Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, the seminal business school text on negotiations, authors Roger Fisher and William Ury use their first chapter to tell us why not to bargain over positions. It doesn’t take long to see how clear cut the positions are defined in the battle for reading instruction: there’s “Team Science of Reading” (otherwise known as drill-and-kill phonics worshipers) and “Team Balanced Literacy” (aka Whole Language wolves in sheep’s clothing).

In Fisher and Ury’s method, they tell us to “insist on using objective criteria.” Wait a minute — isn’t that what research is?

A notable exchange caught my attention when the North Carolina State Board of Education Pre-K-12 Literacy Instruction and Teacher Preparation Task Force met recently. Dr. Barbara Foorman, professor emeritus at Florida State University and arguably the nation’s foremost expert on reading, made a fervent plea to add the word “current” before “science of reading” in North Carolina’s foundational definition of high-quality reading instruction.

Foorman said that the term “science of reading” has become simplified and static, when in fact research continues to grow and build on itself. As an example, Foorman shared that the 2000 National Reading Panel did the best with what they knew at the time, but due in large part to advances in reading research and new knowledge about reading instruction, we know even more now. She wasn’t saying to disregard the research; she wanted us to signal that we will keep doing the best with what we know now, and stay curious. Foorman believes we should be “grounded in the current science of reading.”

When in the hands of some advocates, research too easily becomes at once simplified and static. It makes sense why: advocates are tasked with pushing us to action by convincing us of irrefutable solutions, of “no brainer” silver bullets. And yet most researchers that I’ve encountered are as willing to tell what their research found as they are the limitations to their studies. Advocates, and those they are trying to convince, don’t have the time or patience for those caveats. Just cut to the chase and tell me what needs to be done/funded/legislated.

Do not misunderstand me: We do get to a point when research has been replicated and confirmed so much that it is indisputable. Clearly, this has happened with phonological awareness and the alphabetic principle. And when reading research becomes indisputable, it’s incumbent upon us to ensure it gets in the hands of teachers.

But we go awry in the research-to-practice transfer in two primary ways: (1) in simplifying the research, we make it vulnerable to misinterpretation (“Phonics alone will cure all!”), and (2) we push the “what” without paying attention to the why, where, when, who, and how. More often than not, opponents of systematic, explicit phonics instruction are responding to half-hearted, incomplete implementation.

I almost penned a reflection on what we learned from Mississippi’s approach and my “top five” (there’s always five) recommendations for North Carolina. It would go something like this: “Step 1: Mississippi invested in training teachers in the science of reading and hired high-quality coaches, therefore North Carolina should do the same.”

That may be true, but by declaring such, we’d be repeating an identical approach to what we did eight years ago with the enactment of Read to Achieve: “What did Florida do? Okay, let’s try some of that.” Without asking the other W’s Linda Ellerbee impressed upon me: Why? How? Where? Who? When?

There’s a lot to learn from Mississippi’s impressive turn. But if we stop at “what” they did, we are sorely missing an opportunity to really learn from their approach. If there’s anything to take away from their story, it’s that a coherent approach focused on implementation fidelity (how), supporting teachers and steered by steady, determined leaders (who), begun in early childhood and built up through early grades (when), concentrated on the lowest performing schools (where) can lead to significant improvement in early grade reading achievement.

And why? I think we all can agree on that.

Editor’s note: The Belk Foundation supports the work of EducationNC.