|

|

Early in his third term, former Gov. Jim Hunt defined his signature initiative as “Smart Start,” which has given North Carolina an extensive public-private network of supports for children and parents. Subsequently, former Gov. Mike Easley coined the term “Learn and Earn’’ for his initiative that has resulted in more than 100 early colleges and innovative high schools across the state.

The success of these public policy initiatives, of course, had more to do with political leadership and the quality of the ideas than the catchphrase the governors attached. Public discourse often involves governors, legislators, journalists, and advocacy groups grasping for slogans, deploying shorthand and acronyms, and otherwise seeking to cut through complexity. Now, however, no clarifying simplicity has propelled the sweeping education reforms under consideration by the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Leandro doesn’t have a catchy ring, even when written in italics. It is the name of the first plaintiff listed in the long-running case that led to a judicial finding that all North Carolina children have a right to an opportunity for a sound basic education. Unfortunately, the very term Leandro has gotten caught up in the partisan division of a polarized political era.

To move the constitutional right from words into action in the schools, a superior court judge, along with the parties in the case, developed what is known as the “comprehensive remedial plan.” Not much of a catchy ring there either, or with its acronym CRP.

And yet, as the case may well reach another milestone next week, it is a moment to revisit the multi-layered proposed action plan. Its individual components come across as more compelling – magnets to draw public support – than the leaden terms in court documents and headlines.

The plan calls for systems of “development and recruitment’’ of high-quality teachers and principals. As much research has shown, teachers matter more than any other school factor in student achievement. And the leadership of principals is crucial to creating the conditions to bring out the best in teachers and their students. For both teachers and principals, the plan envisions pay competitive with similar professionals.

The case began as an effort to close the gaps in resources between schools in affluent communities and in low-wealth, mostly rural counties. A central feature of the plan is an all-out effort to meet the needs of so-called at-risk students. Accordingly, it provides for “turnaround’’ assistance to “low-performing’’ schools – and for “adequate, equitable, and predictable funding’’ for school districts across the state.

In keeping with North Carolina’s customary linking of public education to economic development, the plan stipulates that high schools should be more closely aligned with community colleges and universities as well as offer “workforce learning opportunities.”

Especially significant, the plan would reinvigorate and expand North Carolina’s early childhood infrastructure of pre-K, childcare subsidies, and supports for families. It envisions “early childhood learning opportunities to ensure that all students at-risk of educational failure, regardless of where they live in the State, enter kindergarten on track for school success.”

Without resorting to a catchphrase, there is a way to think more clearly and simply about Leandro. Consider this spare sentence in the most recent Highlights of the North Carolina Public School Budget: “All of the 2019- 20 State expenditures were attributed to salaries and benefits except for 6.45%.”

In North Carolina, more than $9 out of $10 for public education go to compensation for people engaged in the enterprise. While education systems require local administrative structure, state government accepted an obligation to assure base pay for principals and teachers nearly a century ago during the Great Depression – an obligation that lives on.

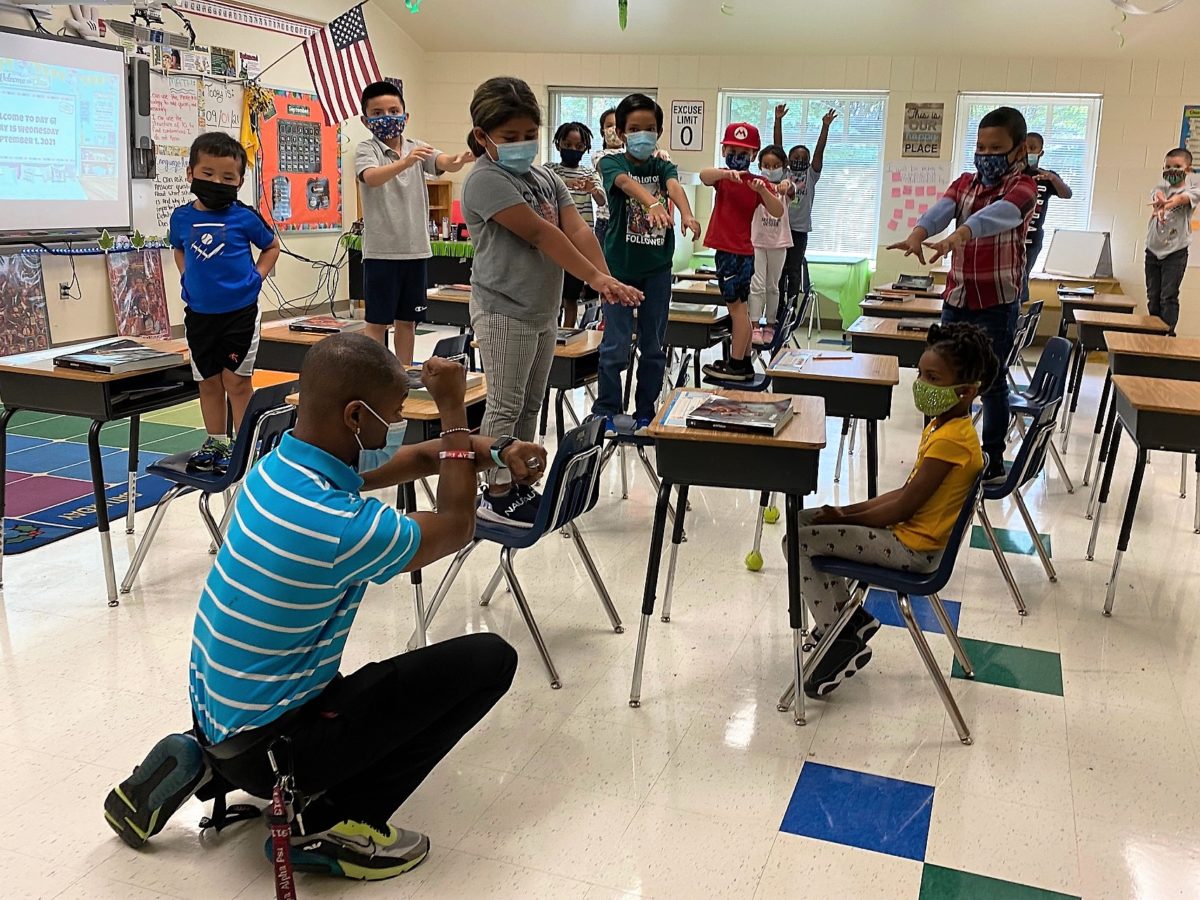

Education is a labor-intensive enterprise; it’s about the daily interaction between adults and young people in a setting structured for learning. Leandro is not about funding bureaucracy; it’s about funding people to enrich the lives of children.

Instead of a new catchphrase, what’s needed is a political recognition and embrace of the essence of the Leandro remedial plan: that North Carolina embark on an eight-year strategy of pay and professional development to assemble and sustain a well-educated, highly capable, diverse cadre of educators.