This is the second piece in a five-part series of perspectives from RTI International on competency-based education amid COVID-19. Follow along with the rest of the series here.

The Oxford dictionary defines competency as “the ability to do something successfully or efficiently.” Merriam-Webster defines competency as the “possession of sufficient knowledge or skill.” Both definitions focus on the fact that competence is directly related to successfully applying skills and knowledge. Creating and assessing competencies in a competency-based education (CBE) system can be described in a few steps.

Defining competencies

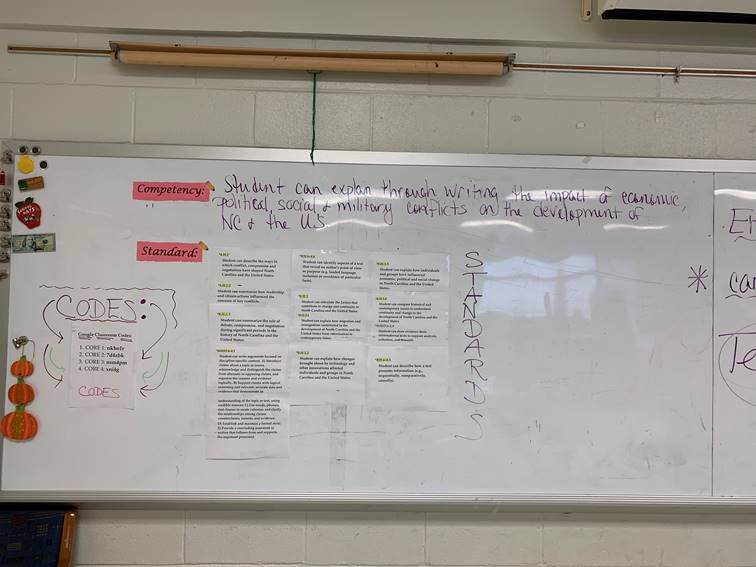

Defining competencies requires the simultaneous action of identifying standards — as standards are broken down into competencies or learning targets, the definition of competency must also be defined. What does it mean for a child to show competence or mastery when completing various tasks across disciplines? Looking at standards for CBE can be wrought with frustration and a laser-focus on academics, but creating competencies does not — and should not — solely focus on what students can do with academic content.

Carroll Magnet Middle School in Raleigh spent a great deal of time creating competencies for their middle school students. This process was a collaborative effort with school leaders working in tandem with classroom teachers to develop three categories for their competencies: growing in social-emotional confidence, understanding how to navigate the digital world, and gaining academic knowledge.

“Academic institutions are no longer focused on academics in isolation,” says Carroll Principal Elizabeth MacWilliams. It is because of this shift that she and her staff have developed competencies that capture the whole child.

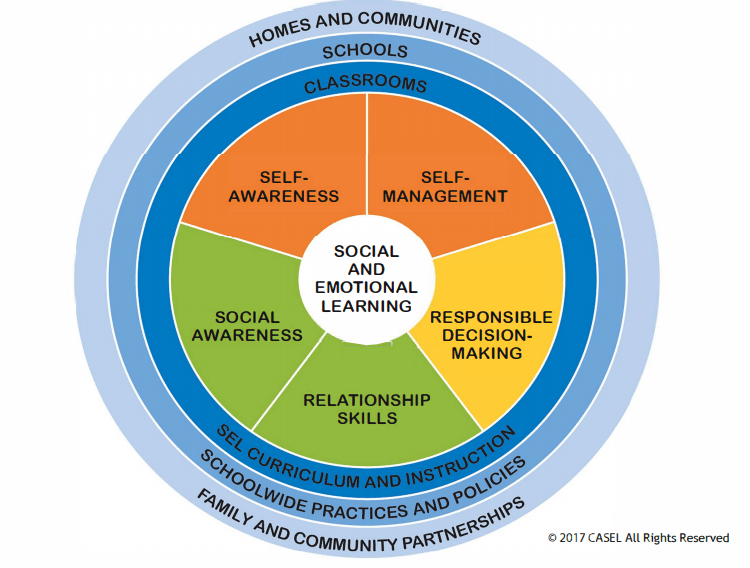

Developing academic competencies naturally draws from content standards, but how can schools develop social-emotional competencies? Carroll looked to the work of CASEL — the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning — and their Social Emotional Learning Framework, which identifies five core competencies to social-emotional learning.

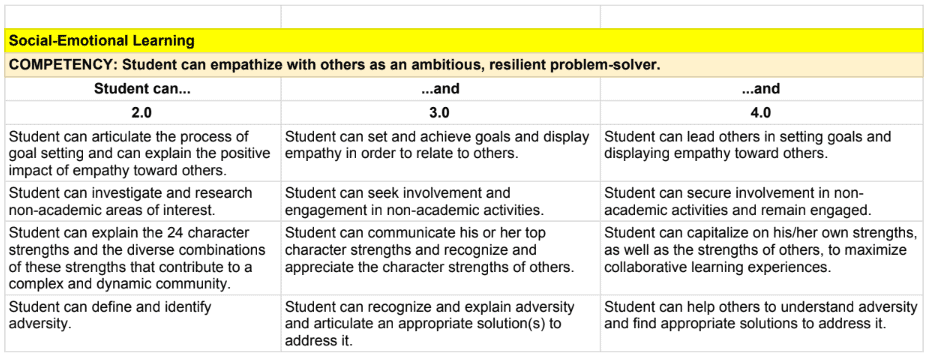

For example, one of Carroll’s social-emotional learning competencies for their magnet theme is: “Student can empathize with others as an ambitious, resilient problem-solver.” The competency builds on the previous skill sets listed in that competency’s CBE rubric.

A full list of Carroll’s Academic Program Guide, complete with course competencies, can be found here on the school’s website.

Assessing competencies

Once competencies are in place and a definition of mastery has been set, assessing competencies can begin. A key difference between CBE and traditional grading practices is that assessing competencies are not “one-and-done” snapshots of a student.

At Carroll, students must demonstrate mastery on competencies at least three times before progressing. Teachers provide clear, specific feedback for students to continue to improve assignments and their broader learning about a topic. Because competencies are not always tied to specific disciplines, there are opportunities for students to demonstrate mastery across subjects — for example, science teachers can mark a student “mastered” on an informational text competency that was developed based on English language arts standards. Further, competencies that are not academic are addressed across disciplines and grade levels.

MacWilliams says that teachers’ expectations for students have not plunged since the start of emergency remote learning. There has certainly been a need for additional grace, but she says the competency framework Carroll has built has eased the transition — as much as a transition during a global pandemic can be eased — to students’ engaging in their learning in a fully remote experience.

How competencies work for every child

The use of competencies — and more specifically, the inclusion of social-emotional competencies — at Carroll has been beneficial during this time of emergency remote learning. MacWilliams believes that if educators do not catch students when they are socially and emotionally vulnerable, then the fact that they graduate with all the academic smarts is irrelevant.

Educators must help students build capacity for resilience and thoughtfulness in their decision-making so that they can be well-rounded solution finders. This sentiment translates clearly into Carroll’s vision: that all CMMS student leaders will be prepared to reach their full potential and lead productive lives as happy, healthy, resilient problem-solvers in a complex and changing world.

There is no better time to live out this vision as education and the greater world in which students live is ever-changing and full of uncertainty. The time of educating young people in the midst of a global pandemic requires that we, as educators, look beyond just academic outcomes and into whether our students know how to identify their emotions, take the perspectives of others, and manage stress.

Considering the use of competencies outside of content standards can not only provide a foundation for students to learn academically, but to also thrive socially and emotionally.

If you have any questions about this article, feel free to reach out to Allison Redden at aredden@rti.org.