|

|

The debate over teaching history itself has a history. Or, as the old aphorism goes, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

What is playing out in North Carolina, ranging from the General Assembly to the State Board of Education to local school districts, represents the contemporary “rhyme’’ of a century of push-and-pushback in racial and cultural dynamics. Chalkbeat, a national nonprofit education news service, lists North Carolina among 28 states with efforts to “restrict education on racism, bias, the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history, or related topics.”

In February, the State Board, by a 7-5 vote, adopted revised social studies standards to guide public schools in teaching about societal conflicts, racism, and sexism in the state and nation. Subsequently, the state House passed a Republican-sponsored bill to prohibit public schools from promoting one race or sex as superior or making anyone feel discomfort by virtue of his or her race or sex. A more extensive substitute bill awaits a Senate vote.

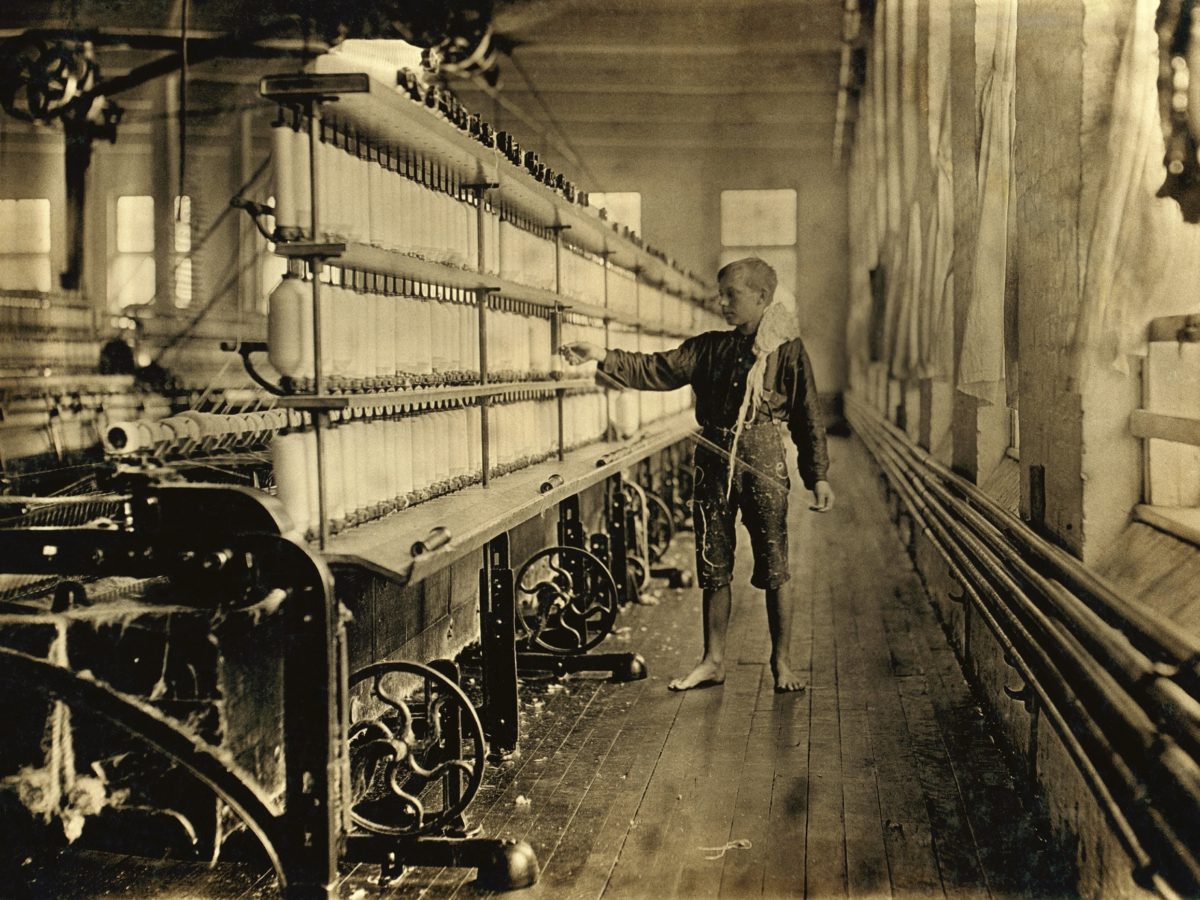

This legislation has antecedents, not in specifics but in approach. Frequently the push came from the trauma of war, from dislocations arising from new technology, from new insights produced by research, and from courageous citizens who protested inequities and strived to expand democracy. Pushback came from cultural traditionalists unsettled by unwelcome social, economic, and demographic change and by reformist activism.

In the 1920s, as the United States adapted to the aftermath of World War I and the era of industrialization, there arose across the South efforts to prevent the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution. The Scopes “Monkey Trial” in Dayton, Tenn., which featured the clash over Biblical interpretation and freedom of belief between Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan, remains a signature episode of that period.

In 1925, the North Carolina General Assembly debated a measure to prohibit public schools and colleges from teaching evolution but, unlike the Tennessee legislature, did not enact a prohibition. Still, the debate produced one of the memorable quotes of Tar Heel politics by Sam J. Ervin Jr., then a young state representative who later chaired the U.S. Senate Watergate investigation. Ervin debunked the bill, saying, “The monkeys in the jungle would undoubtedly be delighted to know that the North Carolina legislature has absolved them from all responsibility for the conduct of the human race in general and that of the North Carolina legislature in particular.”

In the 1950s, as the South and nation adapted to the aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II as well as a wave of fretful anti-communism, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered racial integration of public schools. The landmark ruling undermined Jim Crow segregation and to some extent the Lost Cause narrative taught across the region.

North Carolina responded with a mix of legislation that amounted to a go-slow, token-desegregation strategy for more than a decade. Unlike Virginia, North Carolina did not close schools. And yet it took further federal court rulings to push the South into full lawful compliance in the early 1970s. In North Carolina, whites-only segregated academies “popped up all over the state,’’ write Ethan Roy and James Ford. “Most whites, though, stayed in the public school system and sent their children to desegregated schools.”

In 1963, reacting to civil rights protests among college students and to U.S.-Soviet tensions, the North Carolina legislature passed a law prohibiting communists from speaking on state-supported campuses. The Speaker Ban, as it was known, violated the constitutional protection of speech and threatened the accreditation of the University of North Carolina. In Chapel Hill, students demonstrated the senselessness of the law by having a prohibited speaker address students from the sidewalk just outside the low stone wall of the campus.

More recently, reacting to a Charlotte ordinance, the legislature enacted House Bill 2, more popularly known as the “bathroom bill.” The law, which prohibited transgender people from bathrooms and locker rooms designated for their gender identity in schools and government buildings, created a furor that hurt the state’s economy and became a 2016 campaign issue. Soon after his election, Gov. Roy Cooper and Republican lawmakers negotiated an unraveling of the law.

Now at stake is whether courses of civics and history in North Carolina public schools will have sufficient robustness and comprehensiveness to engage students to think more deeply about the rich, complex stories of their state and country. Wrapped in language of impartiality and even-handedness, the pending legislation leaves teachers vulnerable and inclined to excess caution in classrooms in which no student can be made uncomfortable.

Deep currents – and divisions – along lines of culture and partisanship, religion and race, gender and generations have long coursed through American democracy. To understand current events is to confront and absorb the ways in which history rhymes.