Let’s turn for a few moments away from the narratives of negativity and dysfunction, of crisis and emergency. Instead, let’s point to and ponder alternative narratives that round off the story of public education in North Carolina.

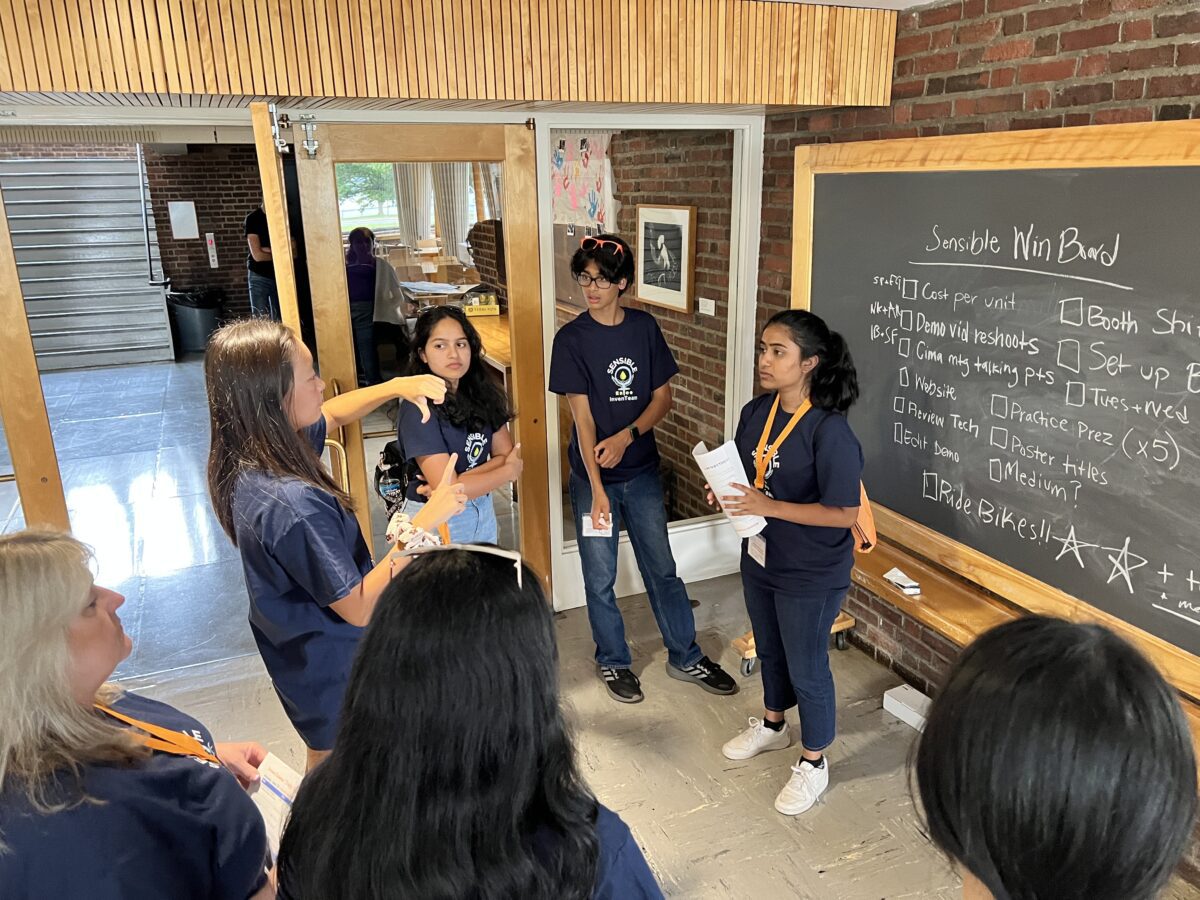

At Enloe Magnet High School in Wake County, a team of nine students recently won a $10,000 grant to pursue their inventive idea to improve screening for cervical diseases. The Enloe students were among 10 teams across the United States selected by the Lemelson-MIT Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Most cervical cancer deaths occurring in developing nations are due to lack of diagnostic facilities and personnel,” says the MIT program in explaining the goal and significance of further Enloe research.

“The Enloe High School InvenTeam seeks to approach this lack of healthcare by designing a menstrual hygiene product that can utilize naturally discharging menstrual blood (menses) to screen for cervical diseases. To adopt menses as a diagnostic medium, the team will invent a low-cost, lab-free, and easy-to-use product sufficient for collecting, sampling, and, ultimately, analyzing life-threatening diseases.”

Enloe became a gifted-and-talented magnet school in 1980-81, among the early magnets established in the Wake County Public School System. The school of 2,346 students is known for its annual student-run charity ball and for its splendid musical productions. You can read the article — of professional quality — on the MIT grant in the student Eagle’s Eye publication.

Another North Carolina high school has won the top national ranking from U.S. News for 2023-24. The Early College at Guilford placed first among nearly 18,000 schools across the nation. U.S. News based its ranking on six factors, including state assessments and preparation of students for college.

This early college is a relatively small school of 196 students, who earn both a high school diploma and college credits. It operates as a partnership of the Guilford County Schools and Guilford College, a private liberal arts institution.

“Because of this partnership,” U.S. News observes, “the curriculum is writing intensive, and students in the ninth and 10th grade take honors and Advanced Placement courses. Students in 11th and 12th grade take college courses with undergraduates taught by college professors, including organic chemistry, linear algebra, modern art, health economics and more.”

Early colleges in North Carolina originated two decades ago as the centerpiece of Gov. Mike Easley’s “Learn and Earn” initiative. North Carolina now has 134 Cooperative Innovative High Schools, most of which are early colleges. Of these high schools, 118 are connected with community colleges, 11 with campuses of the University of North Carolina system, and five with independent colleges, including Guilford College.

While early colleges have spread across the nation and serve as a North Carolina success story, two recent initiatives offer the promise of spinning off best practices. In 2016, the General Assembly established laboratory schools to be run by nine UNC campuses to promote evidence-based teaching and school leadership.

Beginning in the 2017-18 school year, the State Board of Education allowed the use of the “restart” model as a turn-around tactic for low-performing schools. Restart schools get administrative flexibility akin to public-funded charter schools.

“Among 148 schools in the first five cohorts of schools, which had adopted the restart model through the 2021-22 school year, 109 of them, or 74%, had either met or exceeded their growth goals under the state’s accountability measures,” the state board’s newsletter reports.

In addition to lab and restart schools, North Carolina now has more than 40 public schools with STEM designation. They include not only such lighthouses as the N.C. School of Science and Math and the STEM Early College at NC A&T State University but also two schools in Surry County and three in Greene County among several in rural districts.

In 2010, the North Carolina Science, Mathematics and Technology Center pushed for the development of STEM criteria. The state board and the Department of Public Instruction designate schools that meet STEM standards.

To cite such examples of student achievement and institutional strengthening is not to downplay the seriousness of what’s happening in and to public education. Too many schools with teaching vacancies. Not enough bus drivers. Post-pandemic lag in reading and math. A state budget not likely to pay teachers as professionals or to put North Carolina on steady path to a sound basic education for all.

Still, even at this fraught moment, it’s worth telling a fuller story of public education. North Carolina educators and students will succeed in schools dedicated to and supported for success.

Editor’s Note: Shailen Fofaria is part of the student team at Enloe High School. Shailen is Rupen Fofaria’s son.