For an inspirational centerpiece in his second inaugural address, Gov. Roy Cooper reached back to a landmark moment in North Carolina history. After 14,000 of its people perished in the flu pandemic of 1918-1920, said the governor, “North Carolina roared back” in the 1920s with manufacturing jobs and a surge of road building.

“Just as we did one hundred years ago, North Carolina is ready to roar again,” Cooper said. If he had spoken to a live audience — rather than in a COVID-required video — that line would have gotten a burst of applause.

An inaugural address is an exercise in political leadership, not a history lecture. Still the governor’s remarks invite a review of the 1920s for its lessons and its cautions.

That decade, as long-time UNC historian George Brown Tindall wrote, featured two conflicting images: “the benighted South and the progressive New South.” In his 2008 book on Tar Heel politics, Rob Christensen observed that a “social conservatism” coexisted with a “business progressivism,” and he wrote, “The 1920s underscored North Carolina’s progressive paradox like no other decade.”

Under Gov. Cameron Morrison, elected in 1920, the General Assembly approved a series of bond issues for road construction, beginning in 1921 with $50 million ($723 million in today’s dollars). Morrison became known as the “good roads governor.”

The 1921 legislature also reduced reliance on property taxes by shifting to graduated personal and corporate income taxes. Through the ’20s, the state increased support for public schools, but more notably, it approved a bond issue and appropriations that vaulted the University of North Carolina into a top-ranked academic institution.

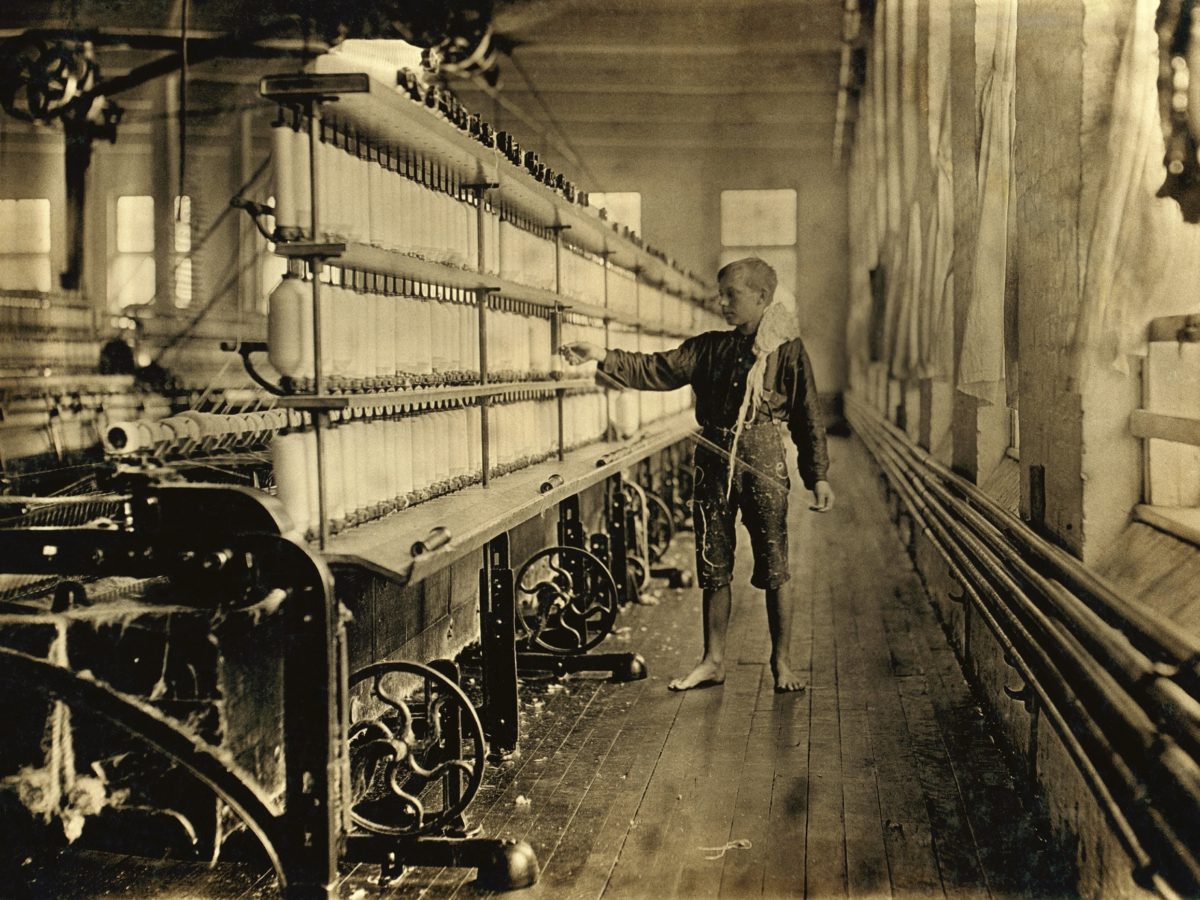

By the mid-’20s, North Carolina had become the South’s leading manufacturing state as more and more North Carolinians worked by the clock inside rather than under the sun outside. For most laborers, low-wage, long-hours work in textile, furniture, and tobacco factories represented a step up economically from more grueling farm work.

And yet, bold governmental initiatives and industrial advances were accompanied by strong resistance to social and cultural change. In his classic The Mind of the South, W.J. Cash of Charlotte, titled the chapter on the 1920s, “Of Returning Tensions –Years the Cuckoo Claimed.”

White supremacy ruled. The Ku Klux Klan roamed. Poverty, illiteracy, and illness ran rampant. Tenant farming was pervasive. Blacks fled one-horse farms and one-industry towns for economic opportunity up north. Historian Samuel Huntington Hobbs wrote that North Carolina, then a heavily rural state of about three million people, exhibited “excessive individualism” and “excessive rural mindedness.”

Rigid racial segregation kept white students and Black students in separate and unequal schools. Black schools were funded, and Black teachers paid, at about half the level of white schools.

To advance their children’s education, Black North Carolinians cooperated with the philanthropy of Sears, Roebuck executive Julius Rosenwald, who offered financial assistance for school-building in Black communities that raised matching funds. “Although the state ranked only fourth in Black school-age population, it led the South in Rosenwald facilities, with a total of 675,” UNC historian James Leloudis wrote in Schooling the New South. Leloudis also pointed out, “North Carolina’s Rosenwald schools were built by a system of double taxation in which Black parents first paid their regular school levies and then dug into their pockets once more to raise the matching funds that the Rosenwald program demanded.”

Across the South, the 1920s also featured efforts to prevent the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution. In mid-decade, the North Carolina General Assembly debated a measure to prohibit public colleges and schools from teaching evolution. It went down to defeat after Sam J. Ervin Jr., then a young state representative who later chaired the U.S. Senate Watergate investigation, opposed the bill with a speech in which he declared that “candor compels me to confess that its passage would produce one happy result. The monkeys in the jungle would undoubtedly be delighted to know that the North Carolina legislature has absolved them from all responsibility for the conduct of the human race in general and that of the North Carolina legislature in particular.”

At the end of the decade, the stock market crashed, leading to the Great Depression of the 1930s. How North Carolina fared in and responded to that huge crisis is the story for another day. For now, Governor Cooper has a valid point to make in the power of governmental investment — and having won a second term, he has a four-year opportunity not simply to lead the state to “roar again” but to roar more robustly for its citizens in economic and educational need than in the 1920s.