Every year, hundreds of billions of dollars will evaporate from the U.S. economy due to permanent learning shortfalls post-COVID, by McKinsey’s calculation.

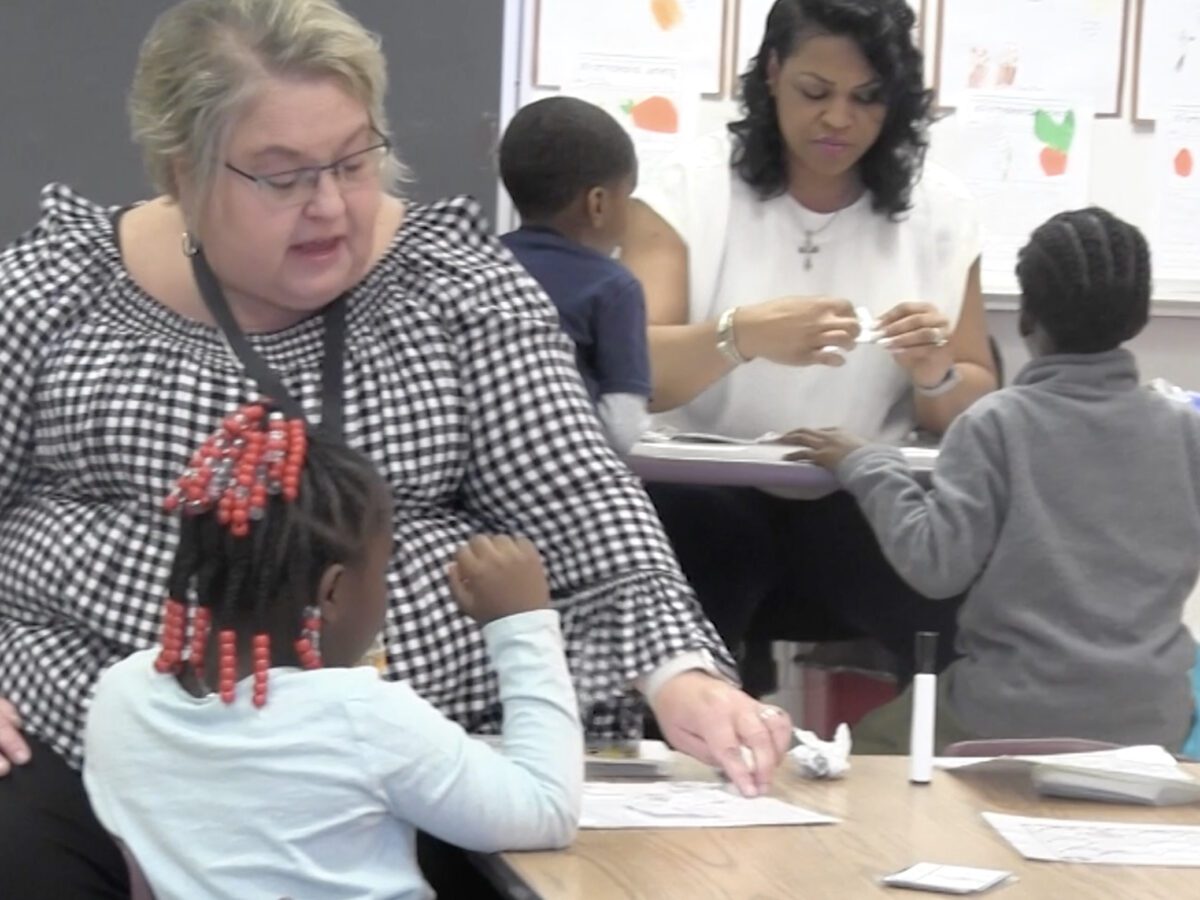

Research has shown high-dosage tutoring is crucial to addressing these shortfalls. In effective high-dosage tutoring, tutors provide students with at least 90 minutes of tutoring per week, aligned with the school’s curricula, in small groups based on their learning data, to build relationships and meet students’ instructional needs. Tutors grow their knowledge and skills through professional development and coaching.

But far too few students in North Carolina get this sort of tutoring.

Is there a way to get tutoring to everyone without increasing costs? Yes, by engaging all available adults to create a “tutoring culture”– for all, by all.

Leaders and schools not only must do this, they can. Our team has done the math: Almost all schools could deliver nearly 90 minutes of tutoring weekly to all students across core subjects, and they could reach the students furthest behind with even more. With just 20 weeks of small-group, adult-led learning in the typical 36-week school year, for two to three sessions weekly, student learning surges by well over an extra year, dozens of studies show.

Even small steps toward these goals would produce large learning boosts.

A handful of critical steps makes a tutoring culture possible — within regular budgets, while paying many educators more than usual. And North Carolina schools using the strategic staffing models our team created are pointing the way.

These schools start with teacher-leaders who produce the most consistently high-growth learning, extending their reach to more students by leading small grade or subject teaching teams. The team leaders can organize roles and shift adults’ time to more small-group teaching and tutoring.

Then, schools can use and grow the budding mass of lessons with high standards and aligned tutorials, covering on-standard, prerequisite and advanced content. These provide the “what” for tutoring and are increasingly available free or at low cost. Team leaders can help teachers prepare and further adapt lessons to fit their students.

Schools can take advantage of recent improvements in assessment and data systems to monitor learning and adjust lessons and groups; those we work with do this weekly or even daily. This step prevents static groups based on current level, which may reduce some students’ learning. Educators can maximize their collective impact through scheduled team time to review what students know, discuss why learning is stalled or surging and plan next steps. AI may help teams deepen and speed up their analysis.

Finally, schools focus on prioritizing “small for all, by all.”

Small groups help students feel noticed and motivated. Reducing whole-class time, which leaves some students bored and others confused, may help address mental health and attendance struggles. Small does not always mean one-on-one: overusing individual tutoring, other than as required by Individual Education Plans, reduces student learning class-wide by reducing how many students are reached.

Reaching all students at school is critical — and fair, since public dollars are used. Tutoring isn’t just for students who are currently behind. Students tagged as average, and those who catch up after lagging, also learn far more in short bursts of small-group tutoring than in long whole-class blocks. Limiting tutoring to students who are behind can stigmatize them and leave some permanently toggling between behind and barely caught up, rather than delivering the message class-wide that everyone can learn more.

Every adult who wants to make a difference can contribute. Research shows strong positive effects from tutoring by paid assistants and parents and other volunteers, not just teachers. Tutors without college degrees can obtain them in paid residencies on some of these teams, becoming schools’ next teachers.

Schools pay educators more within regular budgets. Some schools trade funding for vacant specialist positions to pay team leaders more. Others reduce the number of long-term substitutes by converting the funding for chronically vacant teaching positions to pay for paraprofessionals or teacher residents who tutor teamwide, and pay everyone a supplement — a learning boost rather than a drag. Some pay even more using recurring sources, like Title I. Temporary programs and positions can supplement, but are not a replacement for, a permanent, financially sustainable tutoring culture schoolwide, and statewide. A robust economy fueled by student learning surges can fund higher pay for all educators, and other priorities, too.

North Carolina’s leaders have made some big strides toward student success, including the focus and funding for training educators in the science of reading. By incentivizing all schools to build a tutoring culture, now, state leaders, system superintendents and philanthropists have the power to change students’ learning trajectory and lead the way for states throughout the country. Our students — and the economy — deserve nothing less.