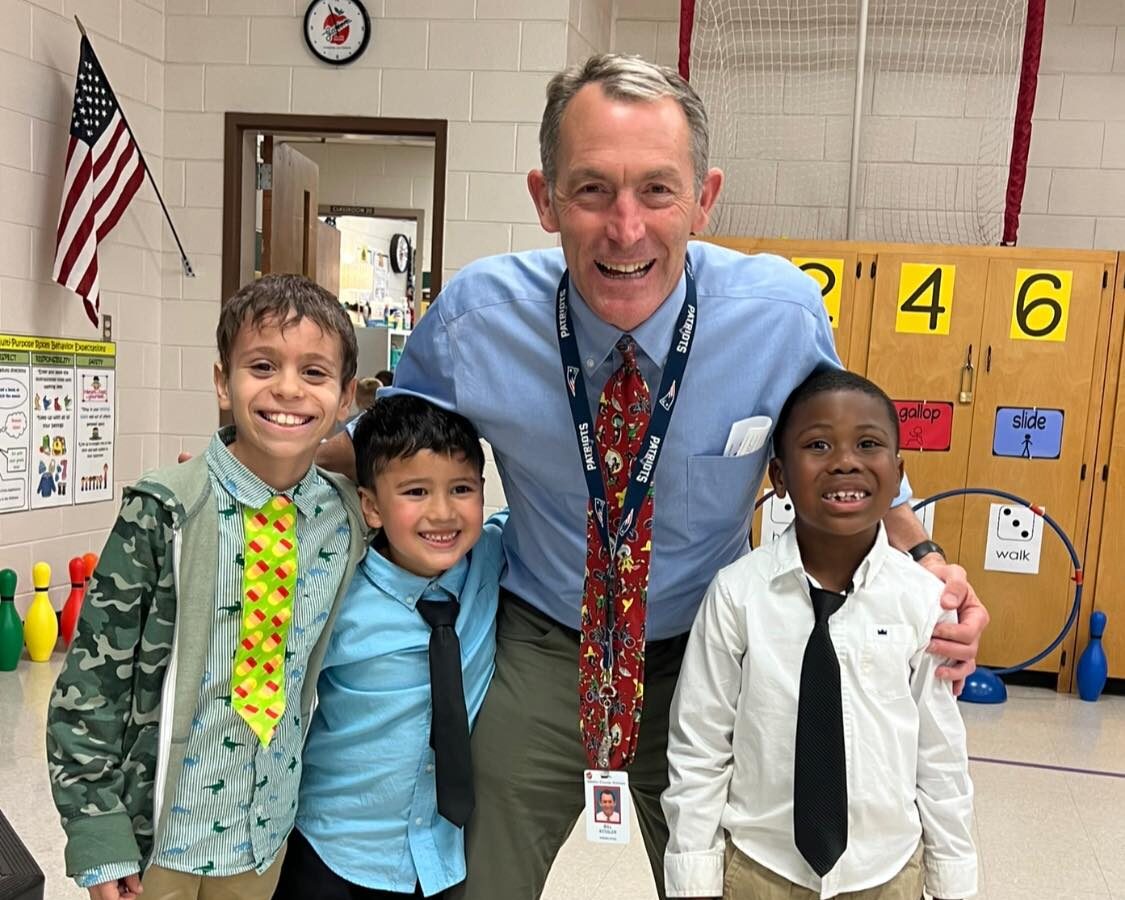

For the past five years, I have been a principal in two so-called “low-performing schools” in North Carolina. I recently completed a dissertation on my experience and the recommendations of high-performing teachers in similar “low-performing” elementary schools. Based on extensive interviews with these teachers, further research, and my personal experience, I see an encouraging albeit different direction for “low-performing” elementary schools that will yield better results and opportunities for students and teachers in these schools.

In the current public school system, elementary schools must comply with multiple accountability requirements based on federal and North Carolina law. Students must take end-of-grade tests from grades three to five in subjects including reading, math, and science. The state assigns a letter grade to each school based on these scores. Schools with low scores receive D or F grades with 80% of the score determined by proficiency and 20% by growth. Teachers whose students score high on these tests for proficiency or growth receive bonuses from the state for their performance. The teachers I interviewed for my study were all high-performers recognized by the state for their excellence in student test scores. The teachers were experts their principals saw as irreplaceable based on their exceptional teaching. These teachers were also leaders who sought to share their techniques and secrets so the entire school would improve and exit “low-performing” status.

Despite their concerted efforts, few of the teacher-leaders were able to generate success outside of their classrooms. They struggled mightily but unsuccessfully to create high-performing schools at the grade level, school level, and even the state level. They spoke of multiple reasons why they ran into obstacles that hindered their actions and attempts.

Nevertheless, they helped me understand a vision of what might make a difference in “low-performing” elementary schools in North Carolina. The way to improve low-performing schools starts with creating and sustaining a collaborative culture at these schools that will attract more high-quality teachers. North Carolina is in the midst of a teacher shortage that is particularly damaging to “low-performing” schools. Leaders need to promote ways to draw the best teachers to these schools. Higher pay is only part of the solution. Teachers seek schools where they can be effective, supported by administration in their instruction, and able to work with their colleagues to further strengthen their teaching. Districts need to assign principals to “low-performing” schools that develop encouraging cultures, committed to growth and performance for all students. Furthermore, districts need to create leadership stability in these schools for five or more years so teachers can build momentum in their instruction, team building, and curriculum development.

Too often the state’s “low-performing” school policy pressures districts to move principals after two to three years. This instability often reduces the attractiveness of “low-performing” schools to high-quality teachers and also drives many top-notch teachers to leave. Many “low-performing” schools now rely on teachers from foreign countries or long-term substitute teachers to cover classes because no one else will teach there. Of course, this dynamic of repelling high-performing teachers from schools most in need only further guarantees future poor performance.

Attracting and retaining high-quality teachers is the first step to turning around “low-performing” schools. The next step is to promote their leadership and agency. The high-performers know how to improve their classrooms and their schools in the most efficient ways. Instead of wasting funds on decisions made without these teachers’ input, leaders of schools and districts should seek high-performing teacher ideas and recommendations. Ignoring their informed opinions wastes time and public funds and results in continued poor performance. Students in “low-performing” schools demand the most cohesive and effective program possible to overcome the challenges of their circumstances. The high-performers can help schools and districts make the best decisions that will help student learning improve. In many “low-performing” schools today, the teachers’ perspectives are ignored, dismissed, or never taken seriously.

Districts and the state should seek to support these teachers rather than blame them for school failure. The teachers I interviewed proposed several ways to provide necessary support. They saw during the COVID pandemic how small classes could immediately impact student learning, behavior, and attitudes. Certainly, class size reduction will help these teachers be able to manage all the challenges their students bring to school daily. The class size limits in kindergarten to third grade should be expanded to fourth and fifth grade. More staff such as tutors, teacher assistants, and psychologists will also provide crucial support to meet student needs.

Another hindrance to school improvement is the state’s school performance grade policy. In its current implementation, it only has made it harder to improve schools. It seeks to turn around schools but only keeps them on the path of worse performance. Districts and policymakers should encourage reform of this policy. The school performance grade relies on student proficiency for 80% of the grade. Proficiency is so highly correlated to family socioeconomics that most results are predetermined. Growth is a better measurement that is less related to family income. Growth would also encourage more students and teachers in these schools. Proficiency scores continually beat teachers and students over the head, leading to less effort and more discouragement. Growth scores promote more possibility and progress and lead to proficiency over the longer term.

At the federal level, end-of-grade tests should be reconsidered. Many elementary schools use other formative tests throughout the year that provide a measurement of student progress compared to national norms. The end-of-grade tests take hours of students’ time to complete compared to these other assessments which are much more age-appropriate for younger children. Combined with standards that are out of reach for many students presently, they do not accurately capture student learning. Many students put forth less effort each year. They know the game, perhaps better than many adults. Students can certainly learn and thrive, but many students in “low-performing” schools need more support and fewer labels. Family socioeconomic status largely determines which schools receive the “low-performing” label. The discriminatory implications of this alone call for a thorough consideration of the current approach.

A new vision for improving “low-performing” schools calls for the following steps:

- Make low-performing schools attractive places to teach for high-achieving teachers.

- Promote teacher agency and decision-making in “low-performing” schools.

- Rely on trustworthy research in decision-making.

- Change the school performance grade to a growth measurement.

- Measure proficiency using formative nationally normed tests.

As opposed to the current doldrums of the “low-performing” schools policy, a new approach will inspire students and teachers with hope and the possibility for progress. Blame and pressure need to yield to belief and possibility.