As school doors close for an unforeseen future in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers and administrators are searching for the most effective strategies to persist through this unprecedented event. Although we haven’t seen anything like this in our generation, there are some examples we can look to for guidance: natural disasters.

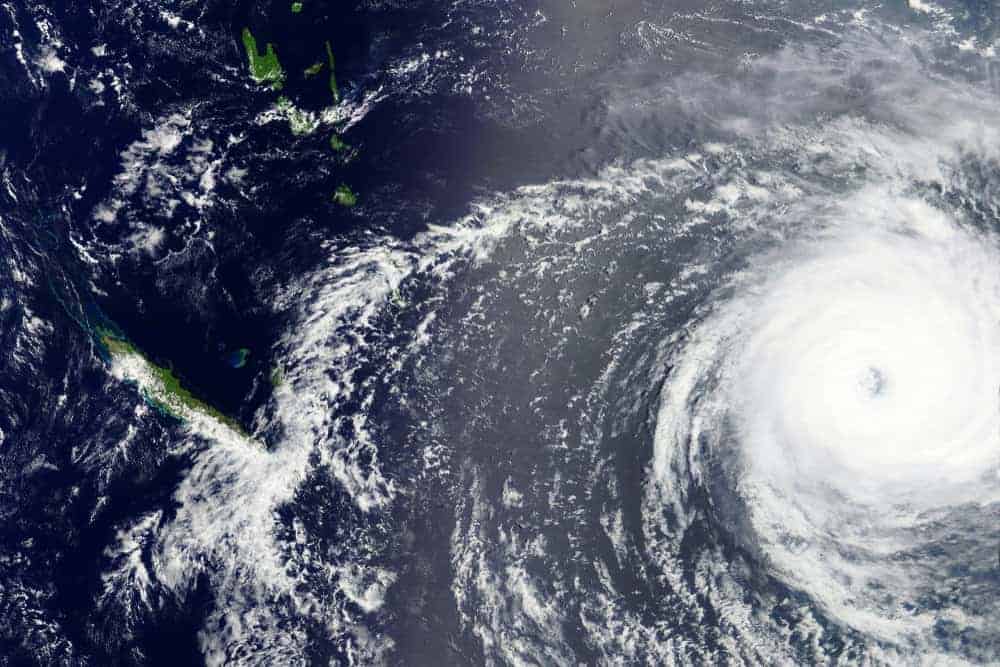

We’ve recently witnessed similar disruptions to education systems from Hurricane Florence in 2018 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, these storms collectively caused 70 direct deaths, produced more than $23.5 billion in damage to North Carolina communities, and disrupted the lives of millions of those across our state. My team and I explored the ways in which hurricanes disrupt schooling for millions of students and teachers, specifically in North Carolina and Texas. Here’s what we learned.

For one, our research results showed that teachers needed support immediately after the storm, but often didn’t get it. Following each hurricane, most of the energy went into ensuring that students were cared for during the chaotic time. Of course, supporting students should always be a priority. Unfortunately, the reality is that this meant teachers were left behind.

When we asked teachers what supports were missing for school personnel, most ranked financial support, free meals, and personal supplies as their top three items. Not surprisingly, of the 1,772 respondents, only 4.5% received financial support, 6.0% received meals, and 8.8% received personal supplies, all of which lagged behind the support given to students. Teachers also affirmed that the hurricane moderately impacted their residence, health, and attendance, as well as their access to food and supplies.

As school districts face COVID-19, educators will need continual assistance and reassurance. This could be through policymakers and administrators asking teachers pertinent questions regarding their needs and the extent those needs are met. Also, this applies to all personnel working directly or indirectly with students — from the office assistant stationed in the school to the superintendent leading the district. All are impacted, and all will need a pulse check starting now. It’s time our policymakers start asking teachers pertinent questions regarding their needs and the extent to which those needs are met.

Our research on hurricanes also revealed the importance of understanding the timeline for recovery. Our work showed that the storms disrupted everyone’s lives, but the period of disruption to schooling lasted long after the event ended.

Schools were closed for an average of two weeks following the storms. However, teachers and students attended school sporadically throughout the remainder of the school year to address personal matters such as removing debris, addressing mental health concerns, and tending to family members. The combined time away from the classroom amounted to be far more than ten school days. Teachers reaffirmed that the storms interrupted teaching and learning for months or even years after the event. Noticeably, the disruption in low-income communities and communities of color lasted longer and was more pronounced.

The current pandemic is already leading to school closures that are far longer than two weeks. While planning for life after COVID-19, schools will need to prepare for a more extended period of recovery.

This will mean patience and planning, as well as acknowledging that vulnerable communities will be affected differently. According to teachers affected by hurricanes, it took time for the system to get back up and running. Teachers, policymakers, and stakeholders should not expect a fully functioning educational system once COVID-19 is under control. This process of recovery will take time, and based on the feedback from teachers and the length of current school shutdowns, this could mean years.

There is no sugar coating here. Our schools have a difficult journey ahead of them, but as an educator and someone who has witnessed revival from the most difficult of tragedies, I am confident that we will make it through this event as well. As one principal told us during our research: “We are a resilient crowd. We are, we’ve got to be.”