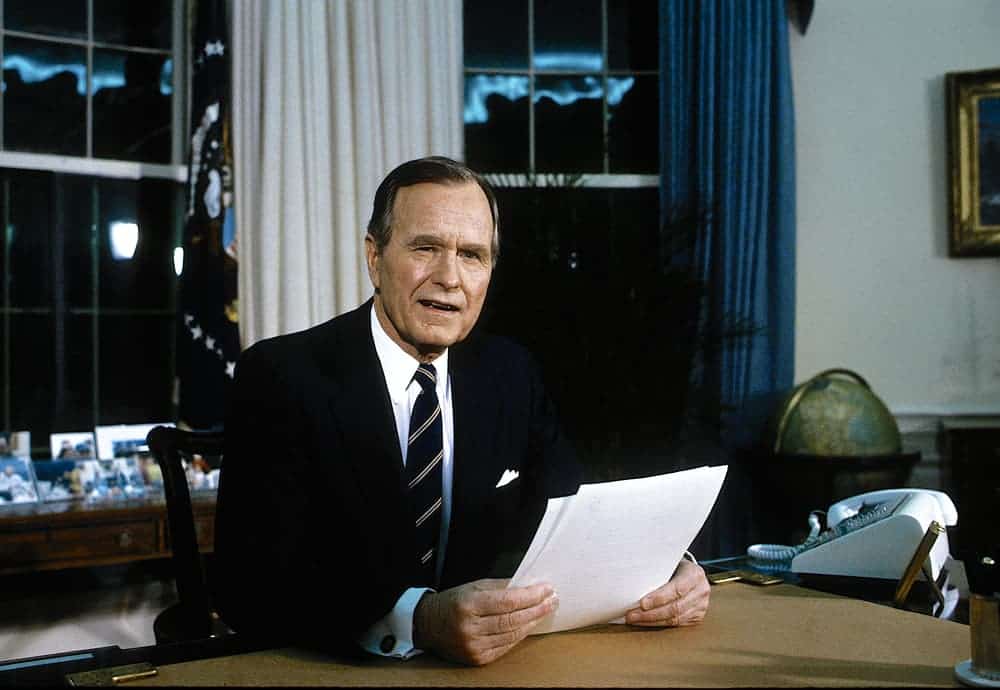

It was a gathering of political leadership hardly imaginable today. Thirty years ago, then-President George H.W. Bush spent two days at the University of Virginia with 49 governors, Democrats and Republicans, to hash out public education goals for the states and nation.

The Charlottesville Education Summit called, among a list of broad goals, for adopting standards to make young Americans competitive with students around the world, elevating the academic performance of at-risk students, and boosting the readiness of children to start school. The summit propelled the standards-and-testing movement that still influences education policy.

To mark the 30th anniversary of the Sept. 27-28, 1989, summit, the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization, published analyses and interviews, including a Q-and-A with former North Carolina Gov. Jim Hunt, in The 74, a national non-profit online education news service. (It’s original name was The 74 Million, for the population of Americans 18 years and younger.)

In two essays, Ross Wiener, director of Aspen’s Education and Society Program, acknowledges the “many legitimate critiques’’ of standards-based reform and says the “recalibration of the role of tests’’ deserves attention. He points out that more than two-thirds of black fourth graders and three-fourths of black eighth graders had inadequate NAEP scores in 1992, but by 2017 half of black students were scoring at basic proficiency or above.

“The goals of the Charlottesville summit were intentionally lofty — too lofty, some critics contend — but it was these big goals set by state leaders that enabled many students of color to no longer be condemned to the dungeons of low expectations where for too long the floor was the ceiling,” Wiener writes. “These achievements underscore that when political leaders commit to action in American education, real progress occurs … But what is most striking is how current debates propose tinkering with the status quo when this is patently inadequate to prepare for the future.”

Wiener urges state leaders to lay a “new foundation.” In his interview, Hunt says the nation needs “a new call to arms.”

At the 1989 summit, Republican Jim Martin represented North Carolina as its governor. Hunt, a Democrat, returned for his second two-term tenure after winning the 1992 governor’s race — and proceeded to pursue the summit’s goals. While public concerns have arisen over test proliferation, he remains an advocate of assessments through testing.

“Assessment is also extremely important,” Hunt says, “and I am concerned about the movement to opt out of testing or reduce the assessments that provide critical feedback to state leaders, the business community, parents, schools and teachers about how our children are growing and achieving … In addition to increased resources, we need to focus on high standards and how to accurately measure learning so that we know how we are doing. We must use that information to focus on how we specifically, tangibly, are going to help lower-income students.”

Over the decades since the summit, the demographic landscape and political profile of North Carolina — and the nation — have shifted dramatically. Polarization of the electorate, the parties, and governors’ postures toward public schools makes it highly unlikely that Democrats and Republicans would assemble as they did in Charlottesville.

And, even before his flout-the-norms presidency led to an impeachment inquiry, President Trump hardly would serve as a convener of an education summit. In his inaugural address, Trump spoke a single sentence on schools, describing his view of “an education system flush with cash but which leaves our young and beautiful students deprived of all knowledge.” The most recent Trump administration education budget proposal would have cut more than $7 billion, including funds targeted to teacher professional development. It proposes $60 million more for charter schools, and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos wants federal subsidies for students in private schools.

In contrast to such current GOP efforts to open exit ramps out of traditional public schools, President Bush, a Republican, drew on the summit in devoting a large section of his 1990 State of the Union address to outlining education goals for the decade ahead. The presidents that followed — Democrat Bill Clinton, Republican George W. Bush, and Democrat Barack Obama — candidly recognized evidence of inadequate schooling by deploying funding and exercising leadership to seek solutions — some worked, some not so much.

“The consensus that informed the 1989 Charlottesville Education Summit and animated education policy for the past 30 years does not currently exist,” Wiener writes. Revisiting that moment in the history of education and politics gives rise to a mixture of dispiritedness and hope: How long will it take for America, and North Carolina, to summon anew the confidence and urgency to propel public education into the mid-21st Century?

Here are additional reports and reflection on the Charlottesville Summit from The Washington Post, The Hill, and Education Week.