Four years ago, Dr. Carmen Graf was the very first principal who applied to be a member of Schools That Lead’s Networked Improvement Community. When she saw the application email, she remembers thinking, “This sounds like a support that would help me reach school improvement goals.”

Carmen loved her school. She worked with great teachers, terrific kids, and families — but far too many students were behind academically. She wanted to join with others across the state to figure out what exactly was going on and take action.

Get clear about the problem

As part of the Schools That Lead Network, Carmen learned that she had to slow down to get clear about the problems her students were having. For an action-oriented principal with a sense of urgency, this is counter-intuitive. Rather than seeking solutions and rolling out new initiatives, Carmen and her team of teacher-leaders studied the problems at hand: they learned about the research that tells us which kids are off-track for on-time graduation by looking at specific thresholds for early warning indicators in attendance, behavior, and course performance.

Understand the current outcomes and set a measurable aim for improvement

Together, they determined how many children in their care were experiencing which specific challenges. They looked carefully at the data and asked where their highest leverage work should be. They learned that many of the students who were struggling academically were missing significant amounts of school, so they focused first on increasing attendance.

“We know from historical data that when kids come to school we have the biggest opportunity to impact them,” Carmen said. “A teacher cannot give high quality instruction when the student is not there. From a practical perspective, it is easy to measure and teachers see the importance of having kids at school.”

Learn by testing small and measuring

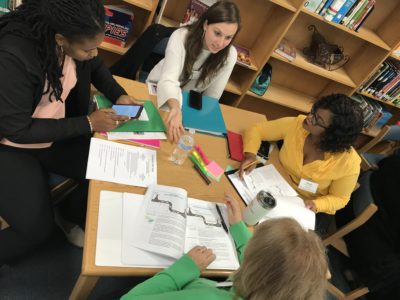

At first, Carmen invested in her improvement team of four: herself; her instructional facilitator, Jerica Wyant; and two classroom teachers, Juliet Vanderburg and Laura Perez. She allowed time for learning before asking her teachers to lead. They learned how to try small ideas with a few students, measure outcomes over time, and determine what worked for whom and under what conditions. Working with network colleagues across the state, they asked difficult questions, challenged each other’s assumptions, shared learning, and celebrated improvements.

Once they had built confidence and had data that showed improvement, Juliet and Laura led the schoolwide focus on attendance. Carmen remembers stepping back to let her teachers lead. “The most strategic thing we did is that our teacher leaders were the deliverers of the information and the process,” she said. “It was safe. They worked through it together. It was student-centered and teacher-led.”

In January, Jerica, Juliet, and Laura shared the process of testing a small idea to improve attendance with the whole faculty. Ninety-five percent of the classroom teachers opted in.

“Laura and Juliet rocked it out,” Jerica said. “They knew what they were doing. They shared their own improvement ideas and data. They knew exactly how it should go. It was a well-oiled machine because they spoke from experience and had seen success with their own students and we had worked as a team to make the structures accessible and meaningful.”

Only scale what works in this context

Just because an idea worked in one place doesn’t mean it will work in another, so the East Garner teachers at every grade level started by trying an idea with a small set of students to see if it improved attendance for kids who were absent a lot. Focusing on parent contact, they studied carefully to learn whether texts or phone calls were more effective, what kind of messages got parents’ attention, and if time of day mattered. After sharing their data with one another, teachers made adjustments and continued collecting data.

In just a matter of weeks, 44% of the students who had been the focus of the improvement idea had significant improvement in attendance. Fourteen percent of the students moved from 50% attendance or less to 90% attendance or more. A student who has been missing half of classroom instruction who suddenly attends 90% of the time or more will undoubtedly have better academic outcomes.

Advancing a culture of improvement

The improvement in attendance rates is impressive, but what Carmen talks about is the change in the culture of the school. By learning a new problem-solving approach, investing in the people in the building, and learning together, East Garner Elementary is advancing a culture of improvement.

Jerica described the process: “The teachers knew from the beginning that it was their decision. They could choose the idea. They could choose the student(s). They had the power to adapt, adopt, or abandon the idea after three weeks based on the outcomes. I think this last meeting with our teachers, we took it up a notch in our level of professional conversation. What does our data say? Was this effective? Did it lead to improvement? What do these numbers tell us? We didn’t monopolize this conversation … the teachers decided. We just facilitated it. When we do this again and again, it will be routine and just the way we do things. We have scaffolded the process and the learning and the language and the approach — so now we know how to make professional improvement decisions based on data. This work deepened our understanding of what collective efficacy means because we did it. We got clear about a problem in our school, we tested some ideas, and we got improved outcomes. Together! These are the practices and routines we understand now to grow our own and our staff’s efficacy.”

And Carmen knows when they have another big challenge to tackle, her team will be ready.

Recommended reading