Editor’s Note: The following piece is in response to the 2021 Dallas Herring lecture, sponsored by N.C. State University and the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research. Click here for more on the lecture from Gregory Haile, president of Broward College in Florida.

After a zip code analysis revealed that we had the lowest enrollments from the zip codes closest to our institution, Piedmont Community College staff walked the streets of those neighborhoods like evangelists on a mission. Knocking on doors. Handing out college swag. Chatting up neighbors sitting on porches. Asking children what they wanted to be when they grew up. Gathering contact information. Responding to a range of comments and questions from the curious, but unconvinced.

Here’s a bit of what we heard:

“Thought you all just did GEDs.”

“Went over once and told me I had to take a bunch of tests and do a bunch of financial paperwork. I took all the papers they gave me, but never did go back.”

“Told me that the class I wanted wouldn’t start until January, but it was September when I went by there.”

“Don’t have that kind of money.”

“Not one person was friendly to me.”

“Didn’t like school all that much when I had to go. College will probably be more of the same.”

“I already have a job.”

“College is for other people, not me. I’m too old.”

On and on it went. Our neighbors. Students who could literally walk to our campus were not interested in attending our college.

They had not seen our social media success stories. They had not visited our website that touted our scholarships. They were not impressed with our shiny new labs and newly named buildings. They did not believe we cared or that they would benefit from attending our institution.

We were stunned by that feedback. And then we had to accept the truth of it. It is impossible to get potential students to walk through an open door they do not believe exists.

Our very physical proximity to so many who would benefit considerably from our offerings too often finds us taking their enrollment for granted, with field of dreams magical thinking — if we build it, they will come. And yet this group was solidly among those who were not interested.

The remarks from Gregory Haile, president of Broward College, are spot on. Not only are innovative solutions required to truly fulfill our underlying mission to be engines of social and economic mobility, but we must also examine our processes and be more deliberate in the execution of equity-minded enrollment management efforts.

Key takeaways

Haile’s remarks were replete with examples of how differing aspects of proximity impact college going. Whether the challenge is physical, social, or financial proximity, we have a responsibility to assist students in overcoming them to fulfill our mission.

Take note of who is missing.

There is a great deal of conversation around how to create more equitable educational outcomes in higher education. One of the strategies for doing so is to disaggregate institutional data at every level to build interventions that are targeted by audience. I’m reminded of the importance of viewing that data through the lens of the communities we serve, taking note of which groups are underrepresented. Our student body and employees should reflect the racial makeup of the communities we serve, with clear, measurable targets to close the gaps. Haile reminds us that, “Those whom we do NOT serve are impacted by our absence.”

Signal early and often about college going.

For many decades, higher education has enjoyed the perception of being a common good, the place where the individual has “the opportunity to rise to their greatest potential.” Rising income inequalities and soaring costs in higher education have led far too many potential students to question the validity of this blueprint for success.

To challenge this narrative, we must deliberately and vocally signal early and often about the expectation of college going across the population. Through genuine partnerships with secondary schools and with leaders in distressed communities, we are uniquely positioned to persuade potential students of the long-term value of pursuing higher education. Ignoring this changing attitude towards college going, however, may cause our eventual extinction as more students come to the faulty conclusion Haile noted that, “College is not for the likes of us.”

Financial concerns stymie enrollment.

With the lowest price point of all segments within higher education, community colleges are the most affordable, and yet students still struggle to pay our tuition and fees. In North Carolina, college-bound students must complete a College Foundation of North Carolina (CFNC) application, Residency Determination Service (RDS) application and Free Application for Federal Financial Student Aid (FAFSA) application to be admitted and then to qualify for financial aid and often for scholarships as well.

Insight about how students perceive these processes were highlighted in a recent Chronicle of Higher Education student roundtable. One student wisely observed that, “Most colleges think a parent is filling out /those forms/, when very often it is the student, which is a setup for doing it incorrectly.”

Ensuring availability of one-on-one assistance with students while they are in high school is an important strategy to limit transition loss in the educational pipeline. Equally important is ensuring availability of financial aid advisors at convenient times to help nontraditional students navigate multiple systems. This will reduce financial proximity challenges on the front end.

Reaching beyond college boundaries

In rural communities, there are limited resources available for the multitude of needs we face. Smaller populations lead to fewer tax dollars for shared services. From limited public transportation to lack of affordable broadband access and food insecurity, our ruralness hides underlying issues of poverty and low levels of educational attainment. The only way for community colleges to deliver on our educational promises is by strategically partnering with industry, community-based organizations, churches, governmental agencies, and universities.

Accelerated degree completion

One exciting example of such partnerships is that of our accelerated degree completion program in partnership with Caswell County Schools. Four years ago, the superintendent and I were both new in our roles. We lamented the low level of educational attainment and brainstormed ideas for improving it. I shared with her the promising Person Early College for Innovation and Learning (PECIL) housed on our Person County campus. We talked about the financial requirements associated with setting up a separate formal early college and determined that in a county with only one high school, requesting funding for administration of another boutique model was unlikely to be funded.

Then, we realized that through careful marketing and advertising, we could achieve the same outcomes as an early college but with limited additional resources. Thus the idea of an accelerated degree completion program was born. Counselors and advisors from our respective organizations mapped out a pathway of classes that enabled students to simultaneously earn their associate degrees while earning their high school diplomas. And it would not cost the student a dime. The superintendent found money for their share of book costs, along with summer transportation and food costs. Piedmont Community College (PCC) secured additional funding for a full-time career coach and marketing materials for the county to help promote and advise students into the program.

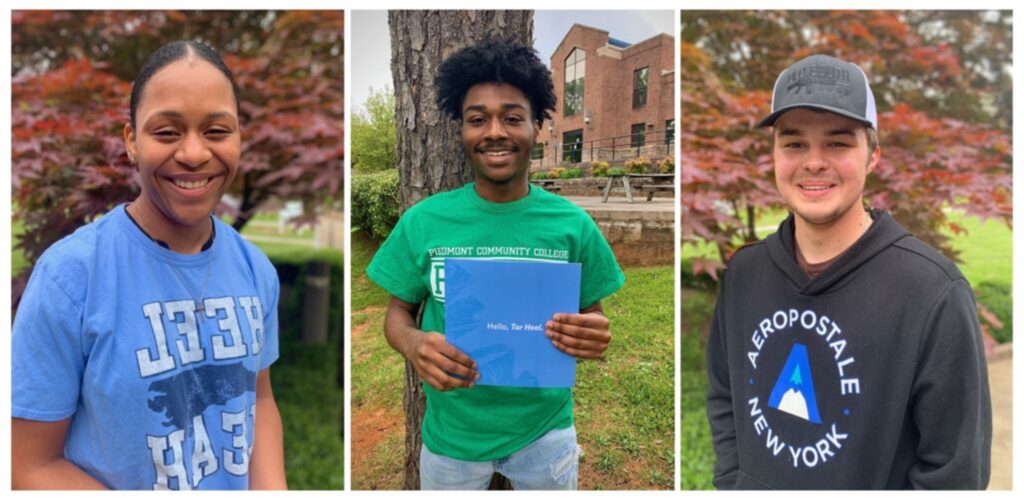

Fast forward four years later. During the 2021 Bartlett-Yancey High School graduation, three students received their high school diplomas and their associate degrees. As they changed out of their high school robes into PCC robes, I shared with the cheering audience a few of the outcomes of this partnership:

- This academic year, students in PCC’s service area completed 2,371 college level courses under the College and Career Promise (CCP) option.

- These students have saved themselves and their families an estimated $60,000 dollars in educational debt (PCC annual tuition and fees versus attendance at a private university for four years) on their way to earning bachelor’s degrees.

The pipeline for the program will yield more than a dozen university-bound and highly skilled graduates in 2022, with anticipated increases for years to come. This partnership not only increases the level of educational attainment, but by advertising it widely and creating a level of prestige, we are countering the notion that college is not for us.

Engaging youth early

President Haile shared that he was not made aware of the concept of college until the sixth grade from another sixth grader who likely had the advantage of implicit college-going expectations from parents with college degrees.

In recognition of having a community with only 16% having obtained a bachelor’s degree, planting seeds of encouragement needed to begin earlier than high school when students are eligible to begin taking classes at PCC. We also wanted to lean into our agriculture tradition and create a better pipeline into those programs as viable career options.

We reached out to a low-performing elementary school to brainstorm how we might improve those outcomes, thereby improving the likelihood of these same students becoming future candidates for the accelerated degree completion program. From these conversations, the “Breakthrough Learning in Agriculture Science and Technology (BLAST)” program was born.

Students in grades 3 – 5 who participate get hands-on experience with foundational skills in agriculture and life sciences infused with literacy skills — reading, writing, speaking, and listening. They will also get exposure to careers in agriculture and learn how our community is working to expand opportunities for our youth to lead in agriculture right here at home.

This afterschool program was designed in partnership with Caswell County Schools, Piedmont Community College, and Shannon Wiley, a 4-H specialist at NC A&T State University, along with NC State Extension Services. It is facilitated by leaders of PCC’s agribusiness technology program and their students.

We are tracking student entry reading test scores and will compare them at the end of the year to see if there are improvements compared to nonparticipants. Our goal is to subsequently expand this program across other elementary schools in Caswell and improve the rate of college going amongst students. We also use this opportunity to provide special outreach to parents to encourage them to begin their own college journey as well.

Innovative partnerships have lasting impact

During the pandemic, the lack of affordable high speed broadband access surfaced more acutely as a critical missing community asset in our rural setting. PCC utilized CARES Act dollars to provide computers to students and employees who pivoted to remote learning and work, and mobile hotspots to ensure access.

We live in a community with such poor broadband coverage that many of the hotspots were returned to us, unused, because the remoteness of our students’ homes could not be penetrated even with a mobile hotspot.

Undaunted, college employees quickly moved to help students in other ways. We added hotspots that could be accessed from our parking lots on both campuses. We gathered businesses and CBOs who were willing to allow similar parking lot access for our students, creating a network of parking lot learning spaces from fast food restaurants to local churches.

This type of action addressed immediate needs. Our work with the Center for Educational and Agricultural Development (CEAD) addresses multiple generational challenges in a remote area. In a series of listening events throughout the county, there were several interrelated needs identified: a lack of formal training programs in agriculture, a lack of farmer access to larger markets, poor health outcomes, a lack of access to healthy food, limited options for safe physical activity, and low interest in new generation farmers.

The college, in partnership with Caswell Economic Development, Caswell County, Extension Services, and many others, began research and planning of what is now called CEAD. This 80-acre combination economic and workforce development project will be anchored by an educational building, farm incubator plots, a food distribution hub, and greenhouses. Within the educational building, not only will we prepare students for careers in agriculture, having added this degree two years ago, but we will prepare entry-level health providers, with that space doubling as a health department-run clinic open to the community.

The incubator plots will be available after an application period and will be operated in conjunction with PCC’s agriculture program. Our agriculture program, like the majority of our degree offerings, have built-in required work-based learning that ensures students have made local agricultural connections, increasing their post-graduation network.

The CEAD project has just completed the design phase, but we already have a food distribution partner from the Maryland area, 4p. They have begun working with local farmers to distribute their products to their customers throughout the South, producing economic benefits before CEAD is operational. Go here to learn more about this project.

Transforming communities through equitable access

Without innovation in our space as community college professionals, we will not be the drivers of social and economic mobility that is hard-wired into our DNA. Examples shared represent the top layer of opportunities that exist to be creative in addressing student challenges related to every aspect of proximity.

I am convinced that with leadership like President Haile as a model, alongside so many other dedicated colleagues, that together we can transform our communities through equitable access to higher education.