The Monday morning after Florence hit, the Onslow County Schools office was closed—as were the schools and many businesses around town. Still, first thing after daybreak, maintenance personnel poured into the office’s parking lot, got in trucks, and left to check on the district’s schools.

“It was just the most amazing thing to see,” said Director of Community Affairs Brent Anderson, who had also come into the office that morning and, until then, was there alone working with no power and no lights. He watched out the window as the parade unfolded. “Here were these guys, who had just gone through the storm, and they were in their trucks and they were going out to check on the schools to make sure everything was okay.”

Everything was not okay.

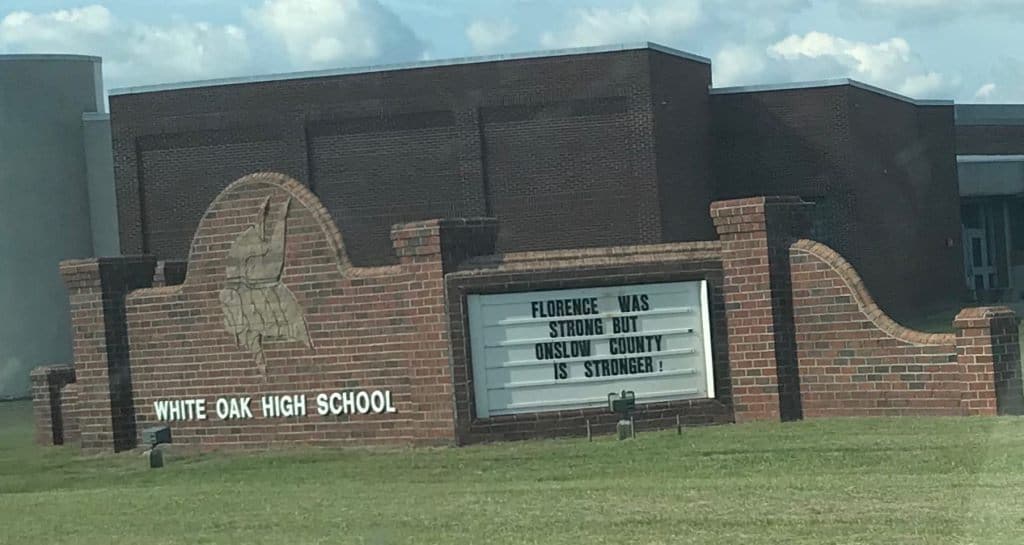

From a human impact, at least 200 students have been displaced from their homes, as well as another 100 teachers. Property-wise, three schools—Southwest High School, White Oak High School, and Northwoods Park Middle School—were most severely hit. In each of those three cases, the buildings’ flat roofs were compromised, allowing in water. Buildup of water in the gymnasiums and elsewhere eventually overflowed into the halls and classrooms. In all, 10 of the district’s schools saw significant damage that may cost an estimated $125 million to restore facilities to pre-hurricane conditions.

“It’s like a triage,” Superintendent Rick Stout said. “We’re going from school to school to school to try to get some of these buildings back in shape in terms of air quality … And what we’re trying to do now is evaluate and make sure they’re safe before teachers come back in.”

The outpouring from the community wanting to help in that effort has been uplifting. They’ve had hundreds of residents volunteer to help with clean up. Of course, because of mold and other dangerous conditions, it is not possible to invite volunteers in at the time. Even administrators were not able to return to their schools until Monday, and they have been asked to wear protective gear and take extensive precautions as they enter classrooms and assess damage.

What they’ve found, in addition to roof damage, is problems with the Internet, damage to computers, bags full of textbooks that have been destroyed, and furniture rendered useless.

Whereas some county schools were ravaged by toxic flood waters entering and sitting in the buildings, the biggest problem in Onslow County was rain. Anderson, who has lived in Onslow County all his life and taught in the schools for many years, said this was the worst he had seen.

“This one came, we watched it. It was agonizing to watch it come,” he said. “It just stayed. The duration of the storm is something that we haven’t seen before. And that led to a lot of the damage that we had.”

While officials are eager to get teachers and students back to school, they are somewhat limited in options. For instance, some counties diverted students from their damaged schools to other, usable schools. However, in Onslow County, the massive growth in the area has resulted in already-overcrowded schools

“We grow on average about 300 students a year,” Anderson said. “Frankly, we’ve got no room at other schools to combine schools and have [students] there.”

Instead, the county is improvising and finding temporary solutions to get schools open as quickly as possible. Contractors are installing temporary roofs, which will only last about two years but will buy time while they figure out a permanent solution.

The schools are sectioning off and closing classrooms and, in some cases, entire wings of schools that are out of commission and making plans to hold those classes in any open room they can find. At some schools, like White Oak, the cafeterias saw major damage, and they are working out alternatives, such as having students eat in their classrooms.

“They’re doing an excellent job of figuring out where they can get the kids on their own sites,” Anderson said. “They’re going to use any available [space].”

While work continues to get the schools ready, teachers have taken it upon themselves to reach out to their students. Some are sending resources and optional assignments for parents to pass onto their kids so that the kids do not fall too far behind or get too far out of the rhythm of school. Others are organizing gatherings to volunteer in the community or just to meet up at a park.

“They’re having get togethers for those kids that can get there,” Anderson said. “And they’re doing work—nothing formal, nothing required. It’s just an opportunity to get together and check in on them.”