|

|

The good news came the day after Sophelia McMannen’s birthday. After 20 years as an educator, she was offered a principal position at Vaughan Elementary School in Warren County.

She made the jump to teaching when two years of working in the business office of a medical center didn’t pan out. At this new school nearby her old district and with a similar student population, she felt ready to take this new leap.

Then she immediately worried.

“Will my district hold me?” she wondered.

Because of a clause in her contract at her previous district, she wasn’t able to start her new position for two months while her previous school searched for her replacement.

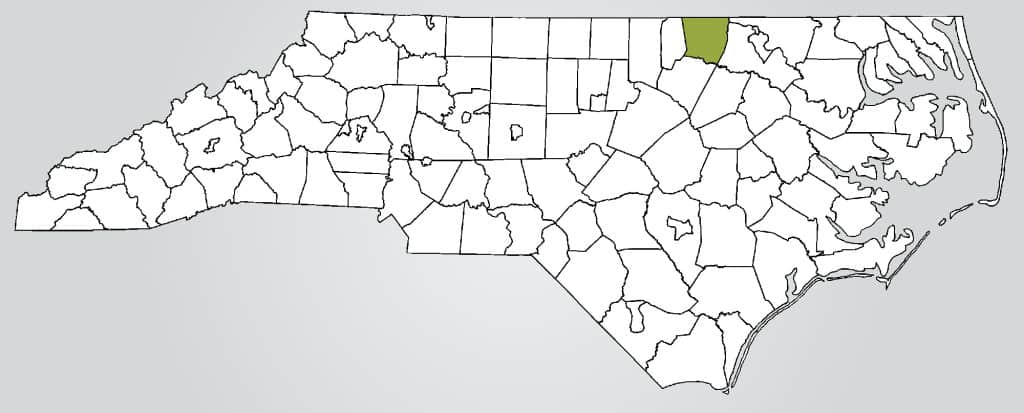

Students and staff at Vaughan Elementary, a small, rural, Title 1 school in northeastern North Carolina, would have to kick off a new school year without a principal — just one example of how the teacher shortage is playing out on the ground.

When Dr. Keedra Whitaker, chief human resources officer for Warren County Schools, heard the news that the school would have to wait for its new leader, she thought back to when she was a principal.

“Once you’ve been a teacher or an administrator, you never lose that lens,” she said.

The school needed to send information to staff, have initial staff meetings, and even plan the open house.

So she got to work. Alongside Chelsa Jennings, the district’s chief academic officer who has been with the district for 27 years, the two made a schedule and a checklist.

Several other central office staff members eventually joined them, and they took turns in pairs performing day-to-day duties at the school until McMannen could take over. Essentially, Vaughan Elementary had a rotation of leaders who over two months and working in pairs took on the role of principal.

“Students need consistency,” Whitaker said.

“It was key to actually creating that continuity,” Jennings added, “to ensure that we provided the school with some stability and consistency throughout our transitions, along with the parents and the community.”

This extra work certainly wasn’t easy, and this school year already came with its fair share of challenges. Educators are navigating the third year affected by the pandemic, and like many districts across the state and country, Warren County Schools is facing a staffing shortage.

The substitute pool has shrunk since the beginning of the pandemic, Whitaker explained, and staff shortages and quarantines have already caused schools to revert to remote learning.

The central office employees haven’t been the only ones taking on multiple jobs — instructional coaches have started teaching, and teachers have given up their planning periods to lead other classrooms.

“When you do have those challenges in any school, the instructional integrity of your school is at risk,” Jennings said. “So you do everything you can to accommodate those areas while our HR department is trying to fill those vacancies.”

And in the meantime, incoming principal McMannen had her feet in two schools at once. While she would come to Vaughan about once a week to start setting up, she spent most of her time at her high school back in her old district.

“So I literally started (at Vaughan) on a Friday,” she said, “and that Tuesday, I gave the ACT (at my old school).”

Despite the obstacles, McMannen was finally greeted on her first full day at Vaughan earlier this month with a Chick-fil-A breakfast and flowers — from her previous school and her husband.

Now that she knows just what kind of team is supporting her in this new district, she’s focused on getting caught up and making sure her students — her “babies” — don’t fall behind.

“Teachers,” she said, “I always say we — and I say we because I’m always gonna be a teacher at heart — you always have to think outside of the box.”

But the shortages are pressing. McMannen said she’s even tried calling universities to see if they can spare any student teachers to fill some vacancies.

“Until teachers can get the support — it’s not even just about money — but the support that they need, you aren’t going to have people that are going to enter the field to teach,” McMannen said. “And I’m praying that it doesn’t, but I feel like it’s going to get worse.”

Behind the Story

EdNC Director of Communications Sergio Osnaya-Prieto contributed reporting to this story.