Public school advocacy organizations and their allies contend that North Carolina is no longer a desirable destination for teachers. They claim that Republican policies, both those related to public education and otherwise, have sullied our state’s reputation in the eyes of the nation’s educators. Nevertheless, data show that North Carolina continues to welcome many more out-of-state teachers than it loses to other states. Even so, lawmakers should consider additional policies that make it easier to ensure that North Carolina public schools can recruit and retain the best teachers in the nation.

Cross-state mobility of teachers

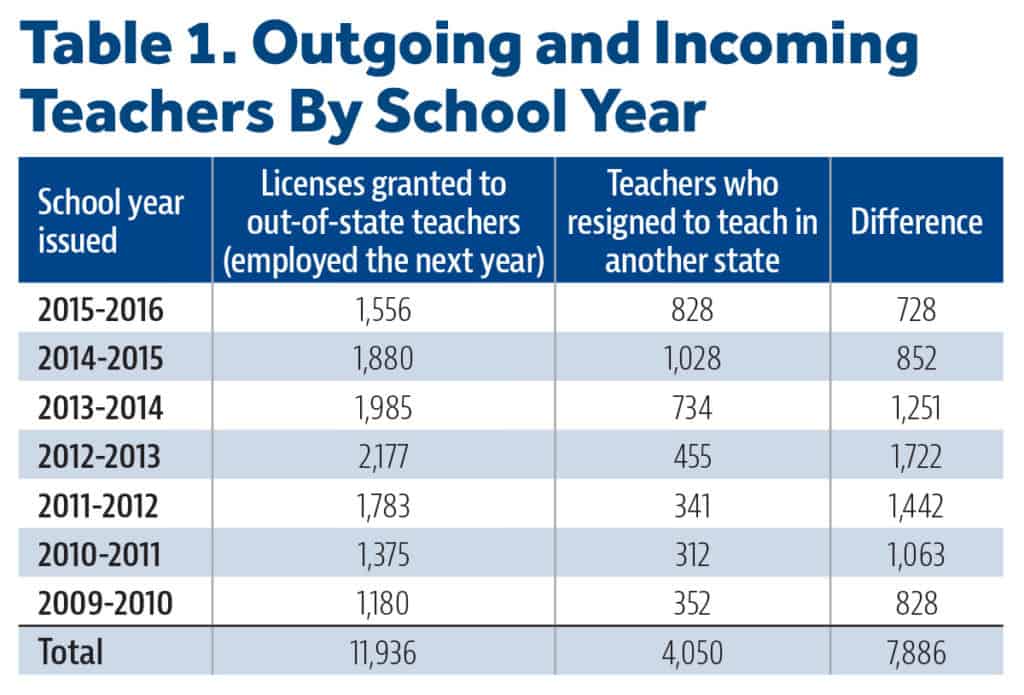

According to North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI) data, the number of out-of-state teachers awarded their initial North Carolina teaching license and employed in a public school continues to outnumber North Carolina teachers who resigned to teach in another state. In fact, North Carolina has licensed more out-of-state teachers than it has lost every year since 2009-10. (See Table 1).

During the 2015-16 school year, North Carolina licensed (via interstate reciprocity agreements) and subsequently employed 1,556 out-of-state teachers.1,2,3 At the same time, 828 public school teachers resigned to teach in other states. All told, the state imported 728 more teachers than it exported last year.

During the 2015-16 school year, North Carolina licensed (via interstate reciprocity agreements) and subsequently employed 1,556 out-of-state teachers.1,2,3 At the same time, 828 public school teachers resigned to teach in other states. All told, the state imported 728 more teachers than it exported last year.

This follows several years of licensing more out-of-state teachers than losing them to other states. Between 2010 and 2016, 11,936 out-of-state teachers received North Carolina teaching licenses and were employed as classroom teachers in North Carolina public schools the following school year. During the same period, 4,050 teachers left North Carolina to teach in another state. The net gain for the state was nearly 8,000 teachers.

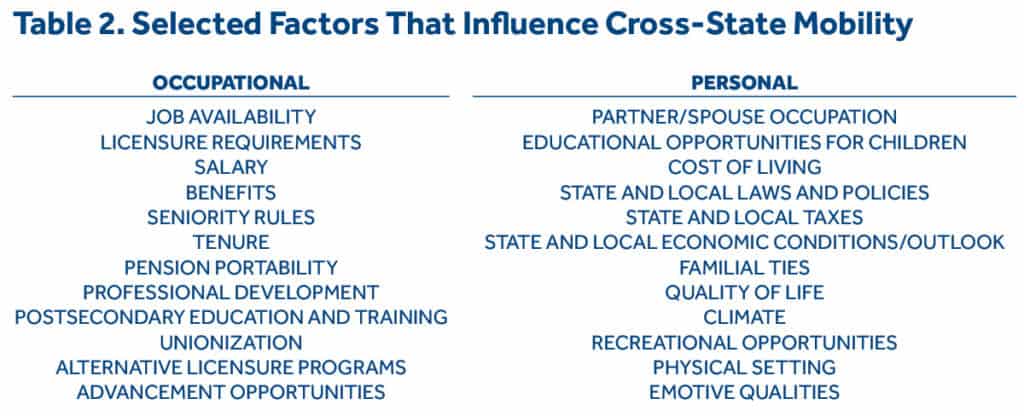

It is not obvious why the number of out-of-state teachers initially licensed and employed in North Carolina dropped for the third straight year. Moreover, as currently designed, the state survey on teacher attrition does not indicate why the number of teachers leaving to teach in other states decreased slightly after four consecutive years of increases. There are a multitude of reasons why a teacher may decide to relocate to another state, and researchers have only begun to identify the combination of factors that play the biggest roles in those decisions (See Table 2).4

It is not obvious why the number of out-of-state teachers initially licensed and employed in North Carolina dropped for the third straight year. Moreover, as currently designed, the state survey on teacher attrition does not indicate why the number of teachers leaving to teach in other states decreased slightly after four consecutive years of increases. There are a multitude of reasons why a teacher may decide to relocate to another state, and researchers have only begun to identify the combination of factors that play the biggest roles in those decisions (See Table 2).4

In their study of teacher mobility between Oregon and Washington, for example, Dan Goldhaber and his colleagues pointed out, “Cross-state mobility is likely to vary over time due to factors that influence the number of teachers being hired (such as population trends and state budget issues), and changes to state policies that affect the cost of cross-state mobility (e.g., pension policies).”5 In North Carolina, the teacher labor market and personnel policies are important, albeit incomplete, parts of the story.

In their study of teacher mobility between Oregon and Washington, for example, Dan Goldhaber and his colleagues pointed out, “Cross-state mobility is likely to vary over time due to factors that influence the number of teachers being hired (such as population trends and state budget issues), and changes to state policies that affect the cost of cross-state mobility (e.g., pension policies).”5 In North Carolina, the teacher labor market and personnel policies are important, albeit incomplete, parts of the story.

Factors that influence the number of teachers being hired, that is, the intrastate circumstances that govern the interstate teacher job market, likely increased the number of out-of-state teachers entering the North Carolina workforce during the Great Recession. For example, much of the increase between the 2009-10 and 2012-13 school years may have been due to both intra- and interstate population shifts and state budgetary conditions.

Theoretically, unemployed teachers in one state may have been more willing to accept a teaching position in states, such as North Carolina, where vacancies were comparatively more plentiful due to population increases and sound budgeting. As economic conditions improved further and revenues to local and state tax revenues rebounded, teachers may have been more likely to find satisfactory opportunities within their home state. Regardless, the number of North Carolina licenses granted to out-of-state teachers appears to be returning to pre-recession levels.

Among state policies that affect the cost of cross-state mobility, however, three education policy areas — licensure procedures, seniority rules, and pension structures — appear to have notable effects on cross-state mobility decisions.6

It has been widely acknowledged that teacher licensure rules play a major role in educators’ decision to teach in another state.7 All states maintain certain baseline rules and regulations for licensure that are consistent with federal requirements. But state legislatures and governing boards may add formal requirements on out-of-state teacher candidates, mostly in the form of additional licensure exams or differential passing scores on those exams.8North Carolina is one of those states.

In fact, North Carolina does not have 100 percent licensure reciprocity with any other state, meaning that obtaining a license in another state does not automatically grant full licensure in North Carolina.9 The prospect of fulfilling those requirements may be enough of a deterrent to out-of-state teachers considering relocating to North Carolina, particularly if they are entertaining offers from districts in multiple states. That said, the National Council on Teacher Quality commends North Carolina for not specifying any additional coursework requirements to determine eligibility for either traditional or alternate route teachers.10

Seniority rules are less of a concern in North Carolina, in part, because teachers are not subject to collective bargaining agreements that require the use of seniority to determine layoff or transfer decisions. State law currently requires school districts to consider structural considerations (duplicative, inefficient, and unnecessary functions) and organizational considerations (needs of the local school administrative unit and program or school enrollment) when required to reduce the teacher workforce.11 Overall, there is little about North Carolina’s seniority rules that would deter a teacher from crossing state lines to enter the state’s teacher workforce.

The same cannot be said of pension portability. In a report published by the National Council on Teacher Quality and EducationCounsel, North Carolina’s pension system received low marks for transparency and flexibility in the state retirement system.12 Only seven states — Alaska, Florida, Ohio, Michigan, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Utah — have portable pension options. Teachers may be more willing to move to states where pensions are portable and flexible, although researchers have yet to quantify the degree to which pensions play a role in those decisions.

Recommendations

Empirical studies alone cannot capture the various personal and professional reasons why teachers decide to leave or relocate to North Carolina. And no two teachers will base their decisions on identical criteria because no two individuals have the same experiences, values, preferences, and goals. If they did, teacher recruitment and retention would be a cinch.

As such, lawmakers have the formidable task of creating and maintaining conditions that make teaching and living in North Carolina as broadly appealing as possible. That is why the North Carolina General Assembly should initiate a multi-year effort to lower tax and regulatory burdens and implement recruitment and retention strategies, including the following:

- Establish a scholarship program to incentivize outstanding college students to pursue a career in special education or science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. There is a nationwide demand for qualified candidates to fill teaching positions in those areas. A deficit of teachers in high-demand disciplines — specifically math, science, and special education — is not something that our state could afford.13

- Offer a sizable salary supplement, alternative salary schedule, or bonus payment to special education and STEM teachers, as well as those who demonstrate excellence in classroom instruction, community service, and scholarship.

- Create opportunities for outstanding teachers to assume new and expanded leadership roles in their schools and districts.

- Add and strengthen programs that expedite the licensure of out-of-state teachers and professionals who do not possess an education degree but wish to enter the teaching profession.

- Offer portable pension options, such as a defined contribution plan or a defined benefit plan with portability features, e.g., a cash balance plan.

- Use Teacher Working Conditions Survey data to inform improvements in working conditions.

Obviously, neither the state government nor school districts can compel public school teachers to remain in North Carolina. In cases where the teacher has not lived up to his or her expectations, we would not want them to. Yet, if North Carolina is losing a multitude of good teachers to other states, then we should carefully reexamine our teacher retention efforts and implement policies and practices that make teaching in North Carolina as satisfying and rewarding as possible. The changes outlined above are appropriate places to start.

Note: The full report is available here.

Endnotes

1. This table does not include visiting international faculty, teachers who received a license but delayed entry into the public school workforce, teachers who obtained a license by means other than an interstate reciprocity agreement, and those who entered a teacher education program at a North Carolina institution upon entering the state and subsequently applied for a North Carolina teaching license. I’d like to extend a sincere thanks to the folks at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (N.C. DPI) Financial and Business Services division for their responsiveness and assistance.

2. N.C. DPI, “Report on Teachers Leaving the Profession” and “State of the Teaching Profession in North Carolina,” 2009-10 through 2015-16, http://www.ncpublicschools.org/educatoreffectiveness/surveys/leaving/.

3. It is important to note that these figures only count those who attain employment. Many others receive state certification and delay their entry into North Carolina’s teacher workforce.

4. As Goldhaber et al point out, “Mobility in the teaching profession is of considerable policy interest, but there is little empirical evidence on the degree to which public school teachers cross state borders.” Goldhaber, Dan, Cyrus Grout, Kristian L. Holden, and Nate Brown, “Crossing the Border? Exploring the Cross-State Mobility of the Teacher Workforce,” Educational Researcher, 44(8), 2015, p. 429.

5. Goldhaber, Dan, Cyrus Grout, Kristian L. Holden, and Nate Brown, “Crossing the Border? Exploring the Cross-State Mobility of the Teacher Workforce,” CALDER Working Paper No. 143, September 2015.

6. Goldhaber, Dan, Cyrus Grout, Kristian L. Holden, and Nate Brown, “Cross-State Mobility of the Teacher Workforce: A Descriptive Portrait,” CEDR Working Paper 2015-5. University of Washington, 2015. See also Goldhaber, Dan, Cyrus Grout, Kristian L. Holden, “Why make it hard for teachers to cross state borders? Phi Delta Kappan 98(5), 2017.

7. See, for example, Arbury, Chelsea, Gerardo Bonilla, Thomas Durfee, Megan Johnson, and Robin Lehninger, “The ABCs of Regulation: The Effects of Occupational Licensing and Migration Among Teachers,” University of Minnesota, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, January 17, 2015; Kleiner, Morris M., “Border Battles: The Influence of Occupational Licensing on Interstate Migration,” Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 22(4): 4-6, 2015; Kim, Dongwoo, Cory Koedel, Shawn Ni, and Michael Podgursky, “Labor Market Frictions and Production Efficiency in Public Schools,” University of Missouri, Department of Economics, Working Paper 16-04, May 2016; Coggshall, Jane G. and Susan K. Sexton, “Teachers on the Move: A Look at Teacher Interstate Mobility Policy and Practice,” Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research, 2008.

8. In North Carolina, teachers with 0-2 years of teaching experience must have completed either a teacher education course or approved alternative program and bachelor’s degree from a regionally accredited college or university. In addition, middle grades (6-9), secondary (9-12), and K-12 license area teachers must earn a minimum score on the Praxis II tests. Elementary education and exceptional children teachers must earn a passing score on the Pearson Testing for North Carolina: Foundations of Reading and General Curriculum test. Teachers who are fully licensed in another state, have three or more years of teaching experience, and either meet approved licensure exam requirements or have National Board Certification receive a license. Teachers who are fully licensed in another state AND who meet NC State Board of Education approved licensure exam requirements OR have National Board Certification are issued the Professional Educator’s Continuing License. See N.C. DPI, “Educator Licensure,” http://www.dpi.state.nc.us/licensure/beginning/.

9. According to N.C. DPI, “North Carolina does NOT have 100% reciprocity with any state. All jurisdictions that participate in the NASDTEC Interstate Agreement may choose to have additional requirements for educators who are coming from another jurisdiction. These additional requirements are known as “Jurisdiction Specific Requirements” (JSRs). Most times these additional requirements vary upon the educator’s years of experience. Some jurisdictions, however, consider themselves “full-reciprocity” and do not have any additional requirements.” N.C. DPI, “Frequently Asked Questions,” http://www.ncpublicschools.org/licensure/faq/.

10. National Council on Teacher Quality, “2015 State Teacher Policy Yearbook: North Carolina,” December 2015, p. 50.

11. North Carolina General Statute 115C-325 (e) (2), http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByChapter/Chapter_115C.html.

12. Doherty, Kathryn M., Sandi Jacobs, and Martin F. Lueken, “Lifting the Pension Fog: What Teachers and Taxpayers Need to Know About the Teacher Pension Crisis,” National Council on Teacher Quality, February 2017. See also Doherty, Kathryn M., Sandi Jacobs and Martin F. Lueken, “Doing the Math on Teacher Pensions: How to Protect Teachers and Taxpayers,” National Council on Teacher Quality, January 2015.

13. Henry, Gary T., Kevin C. Bastian, Adrienne A. Smith, “Scholarships to Recruit the “Best and Brightest” Into Teaching,” Educational Researcher 41 (3), 2012