Every week, we are asking the two candidates for state superintendent of public instruction a question culled from teacher responses to a survey, along with a few additions of our own. This week, we departed from our scheduled questions. Here is what we asked and how we asked it.

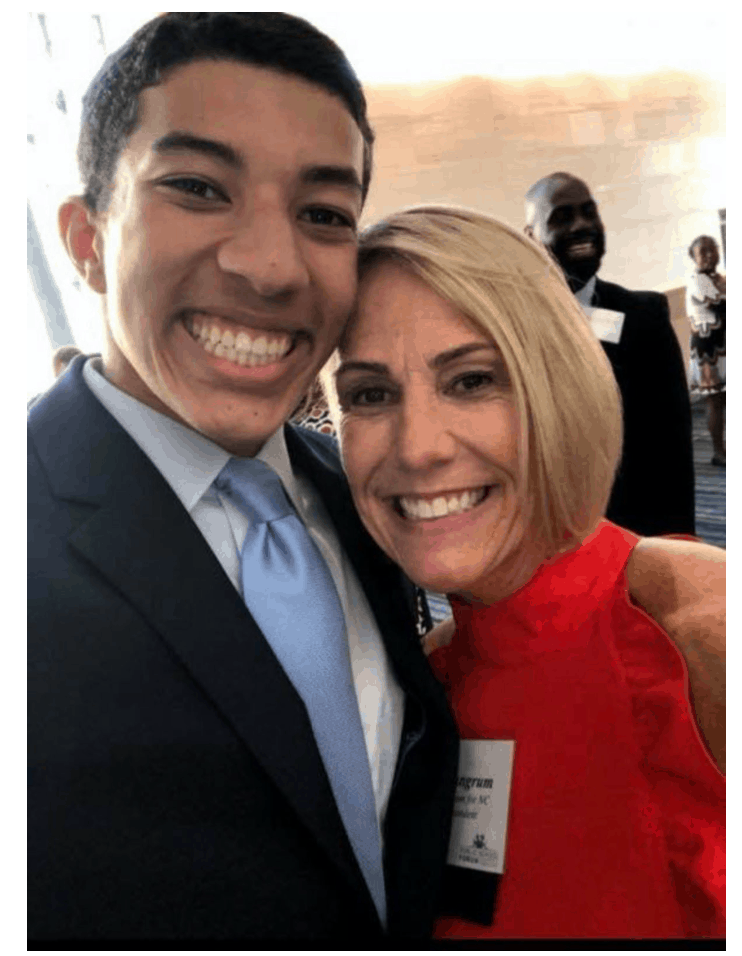

Over the weekend, EdNC interviewed Greear Webb, a Morehead-Cain Scholar at UNC and student organizer, at the #RaleighDemandsJustice event.

Here are four of Webb’s quotes:

“When it comes to anti-racism policies, whether that be in the education realm, the policing realm, the housing realm, young people have ideas.”

“Treat us as students with influence, and as youth with power.”

“Right now, we’ve got a problem with humans not seeing other humans as humans, and that treatment is definitely frustrating.”

“I just ask that America and North Carolina understand and give credence to the anger that those in the black community are dealing with and are facing.”

Here is the question we asked the candidates:

Q: What role do you envision for students if you are superintendent?

Republican candidate Catherine Truitt

During the primary campaign season, we candidates attended A LOT of events. My absolute favorite was a student town hall organized by EdNC and hosted by Edgecombe County Early College. Over 120 students from across four high schools showed up to engage with the candidates on issues that mattered to them. We rotated among a dozen tables, each with 12 students and a question for the candidate. One question addressed the issue of the needs of rural schools and included this statement: We need someone who sees every decision in terms of how it impacts kids in rural counties and who makes decisions with us instead of for us.

I could not have said it better. Education is an endeavor that is about people —adults and students — but when it comes to education policy, students are often an afterthought.

My educational philosophy is rooted in the belief that everyone has a natural right to maximize their human potential, and that the state has a constitutional duty to provide a sound, basic education to everyone. Unfortunately, it is undeniable that a student’s zip code is largely determinative of their future socio-economic status. In other words, if you are born poor, you will stay poor. We have a lot of work to do.

My leadership approach is built around the premise that every decision we make about education in North Carolina must begin with one simple question: Is this what’s best for our students?

I’ve worked in the trenches in a variety of settings: urban, rural, suburban, and high poverty districts. I’ve experienced firsthand the destructive effects of excessive centralization, and a failure to listen or to observe the unintended consequences of well-meaning policies. I have remained in contact with many former high school students, and I follow their lives with interest. They are my extended family.

Greear is absolutely right in his suggestion that there is a tendency in education to assume that because we have done something a certain way for dozens of years, it must be the best way to operate. My entire career has been energized by a sense of innovation and a desire to re-engineer the fundamental way that we think about education. Each generation is different than the one that preceded it, and we need input from current students to help redesign the system to meet their needs.

So how do we ensure that students are at the center of every decision we make?

- As the leader of the Department of Public Instruction, the state superintendent should promote a culture at DPI that is laser-focused on making student-centric decisions, and that values people who have the courage to speak out when we lose sight of what’s important.

- As State Superintendent, I would like to create formal routines that help me remain connected to students in methodical ways. I would balance in-depth contact from student internships (like the one Greear participated in) with a quarterly calendar of school visits by region that include a student round table designed to collect student input from across the state. Every effort should be made to include local legislators at these discussions to ensure that they are also receiving the benefit of student input. Feedback should then be shared out during the Superintendent’s Monthly Report portion of the State Board of Education meetings.

- The state superintendent should always recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to anything in education. By respecting local need and circumstances, it is far more likely that policy outputs from Raleigh will actually serve the needs of students they are meant to advance.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed great disparities across our state in terms of districts’ readiness to deliver high quality online instruction. Now, another fault line is revealed by the protests over racial inequality and injustice that are occurring daily in many communities large and small across our state. In both of these areas we need to look more to students to highlight problems as well as solutions. Who better than students who lived through this year’s pandemic and digital learning to highlight both what went right and what went wrong? Who better than students who walk the halls of our schools every day to point out the racial inequalities and disparities that exist in our schools and to suggest real, meaningful ways to address those?

In these areas, and in many others, ongoing, meaningful dialogue with students will help our educational system deliver better outcomes and make our state a better place for ALL people.

We are on the cusp of great change in public education both nationally and in our state. The times call for an empathetic, technologically savvy Superintendent with a history of engaging proactively and authentically with everyone to solve challenges. With the right leadership, these changes will occur by asking students to walk alongside us rather than keeping them at arm’s length.

Democratic candidate Jen Mangrum

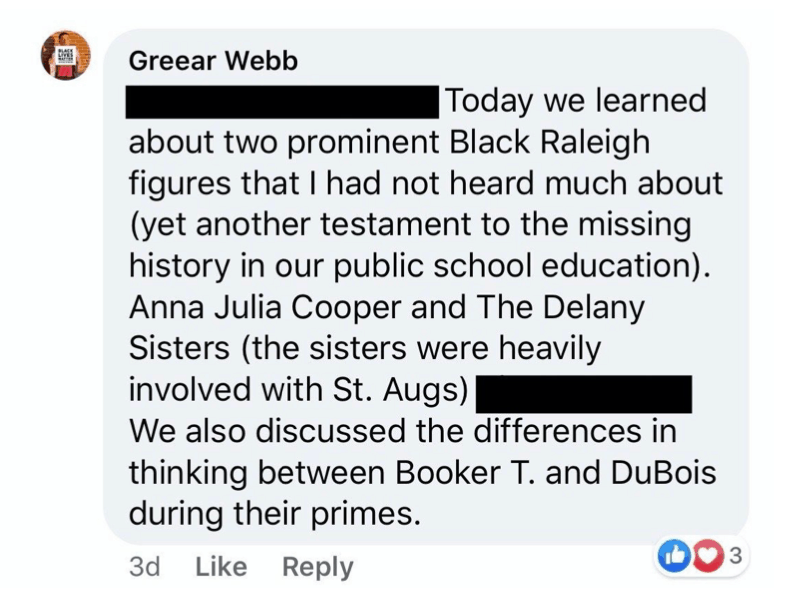

I’ve had the true pleasure of meeting Greear Webb and I keep up with him periodically on social media. Not too long ago, Greear created a post about taking a class at UNC entitled African American History Since 1865. Greear had been excited to learn about Anna Julia Cooper and the Delaney Sisters, prominent black women who were significant players in Raleigh’s history. However, Greear wrote, “yet another testament to our missing history in public education.”

Greear is right.

Our students in North Carolina don’t learn about the important black people in history who impacted our state. Why? The ugly truth, as Winston Churchill once said, is that “history is written by the victors.”

Since the forced arrival of black slaves in 1619, black humans have been deemed inferior. They have been legislated as property, denied land ownership, confined to labor and low wage jobs, segregated with Jim Crow, taught in separate and unequal schools, denied access and opportunity, and even now, murdered without remorse. Our black brothers, sisters and siblings, have always been considered less than by large numbers of white people.

So how do we right that wrong?

According to another one of Greear’s posts where he quotes Professor Robert Porter, “A REAL education should change you. Too many white Americans seem so threatened by change, and by extension, true education.”

The complex, long standing problem of racism needs to be addressed on multiple fronts, but both Greear and Professor Porter know that there is at least one prominent space for making change — public education. That’s where I come in.

For over a decade, I have taught Elementary Social Studies Methods for my university students who are learning to be elementary school teachers. For a variety of reasons, elementary school teachers rarely teach social studies. According to Dr. Daniel Willingham of UVA, less than 5% of instructional time in third grade is spent learning social studies. No wonder only 39% of Americans can name the three branches of government! (Annenberg Public Policy Center) And, when elementary school teachers do teach social studies, they often ignore or are afraid to confront complex issues and instead perpetuate the false narratives they learned themselves in history classes decades ago. These false narratives may include notions like Rosa Parks was a tired woman, not an activist for change, or that the colonists and Native Americans were great pals who enjoyed having a meal together. Partly because of this, middle and high school students enter classrooms not having been exposed to significant minority voices and experiences throughout history.

Unfortunately, this is the educational context I experience firsthand and I agree with Reverend William Barber when he says we should be “rectifying the curriculum.”

So to the question, “What role do you envision for students if you are superintendent?”

I envision our students as engaged partners in their education who know that learning is more than memorizing content and checking off competencies one by one. I agree with Lisa Delpit, a Harvard scholar who researches literacy and instructional practices for black students. She describes successful instruction as constant, rigorous, integrated across disciplines, connected to students’ lived cultures, and designed for critical thinking and problem solving that is useful beyond the classroom. Unfortunately, her research reveals that this type of instruction isn’t provided for every child and we must do better for our black and brown children who are school dependent.

Delpit makes me reflect back on my own time as a third grade classroom teacher and the opportunities I had to teach social studies standards. In one unit, my students researched the roles of adults and children in the 1800s. They created a quilt as part of their assessment and each square represented one of their findings. They raffled the quilt at a school spring fling and used the proceeds for myelin research. You see, they had a reason to learn and a real audience. Matt Murphy, one of their peers, was diagnosed with Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), which is the disease in the famous movie Lorenzo’s Oil. This disease preys on seven and eight year old boys’ and causes their myelin to degenerate. My students wanted to save his life. Throughout that unit, they analyzed primary sources, read books about the time period, wrote a story about the process and participated in the design and production of the quilt.

It was my responsibility as an educator to discover what my students cared about, guide them to use their skills and knowledge, and partner with them to bring about positive change in our community. Ultimately, my students and I didn’t save Matt’s life but we learned a lot over those few weeks about ALD, real life America during the 1800s, and a whole lot about ourselves.

I imagine Greear Webb had similar experiences during his K-12 journey in North Carolina’s public schools. I believe that Greear partnered with his teachers and peers to learn, grow, and make positive change in their community together. As he posted on May 31, “So grateful for my education and mentors for allowing me to see the power of using my voice and speaking up confidently for what’s right.” Now, because of that partnership and engagement, North Carolina will reap the rewards of a young citizen who is partnering with other young folks to combat racism and make us a better North Carolina. Thank you, Greear.