After a year of controversy and a legal battle over what company North Carolina would use to test its early readers, Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson announced recently that next year, districts will be able to choose which K-3 assessment platform they use.

Having missed months of face-to-face instruction because of coronavirus restrictions, students are heading into summer and an uncertain school year in the fall. How districts track students’ reading progress will inform how teachers make up for slips in learning. Research predicts that learning losses will be greater in black and Latinx children and children living in poverty.

Why does assessment matter for student learning, and what will district choice mean for the classroom?

Choice can be empowering for local districts, said Kristin Gehsmann, department chair of literacy studies, English education, and history education at East Carolina University. But districts, she said, have important factors to consider to make sure the assessments are supporting classroom instruction.

“What’s really important here is alignment between what you want students to know, understand, or be able to do, and then you have to make sure the assessment actually measures those things,” Gehsmann said.

The state usually provides only the assessment portion of these programs. In order to improve reading instruction, experts say, more specific diagnostic tools are also needed — as well as interventions and guidance for teachers to know what to do with assessment data.

Districts use a combination of local, state, and federal dollars to purchase these curricular materials and interventions. Some tools are more expensive than others and are up to districts with varying resources to buy, said Lynne Vernon-Feagans, a Frank Porter Graham Institute researcher who studies literacy and issues facing children living in poverty.

After a year of changing programs, training teachers, and being uncertain the state requirement would stick, Greene County Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller said he welcomes the flexibility.

“I think given where we are with everything that’s happened and with all the uncertainty moving forward, I think the best thing that the State Board and the superintendent could do is create a menu of options that are allowable and let the districts make that choice,” Miller said.

He said the district would stick with what it’s using now if possible and, if not, would consider the costs and training requirements of available options.

“Our folks were used to using one program specifically for several years until last year,” Miller said. “Then it changed, and there were a lot of training demands put on teachers for that, and we don’t want to have a repeat… of that on top of all the other things that are being expected of teachers right now.”

Graham Wilson, spokesperson for the superintendent, said a draft policy would allow districts to choose any platform that has been approved by the State Board in the last three years as a local alternative assessment for third grade reading proficiency. Here is that list for the 2019-20 school year.

Wilson said the information from different assessments will be aggregated by using lexile levels — a framework that matches students’ reading level to certain texts and that he said platforms must measure to make that list.

K-2 reading diagnostic results are factored into EVAAS (Education Value-Added Assessment System) growth measures, which are used to measure teacher effectiveness and school performance. Tom Tomberlin, the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) director of district human capital, said the decisions for how schools measure growth are made with an advisory council of superintendents and accountability directors.

“It is really done with stakeholder involvement to make sure we get it right,” Tomberlin said.

How we got here: The last year of controversy summarized

Those two programs Miller mentioned above are owned by two companies: Amplify, which DPI had contracted with for several years to test readers as part of its 2012 Read to Achieve legislation, and Istation, which won the contract in 2019 after state law required DPI to go through a new procurement process.

Amplify protested that decision, claiming the process was unfair and that Johnson tried to influence the decision of the evaluation team assembled to choose a platform.

Department of Information Technology (DIT) General Counsel Jonathan Shaw, who oversaw the case that resulted from the protest, recommended May 27 that the protest be dismissed after Johnson canceled the contract at the center of the case in April. DIT Secretary and Chief Information Officer Tracy Doaks adopted Shaw’s recommended order on June 4.

Johnson said the reason for canceling the three-year Istation contract came from a desire to have a tool in place for the fall. At an April State Board meeting, Johnson said he was working with DIT to start another procurement process.

But at May’s board meeting, Johnson announced that next year districts would choose their own platforms, and a statewide tool probably would be needed in years ahead. He released the following statement last week when DIT officially dismissed Amplify’s protest.

“We are pleased with DIT’s decision today to dismiss Amplify’s protest,” the statement reads. “DPI, under the close guidance of DIT, ultimately conducted a fair, unbiased procurement to identify the best reading diagnostic tool for North Carolina. We are grateful that the year of controversy triggered by the disruption and deception of bad actors seeking political advantage is behind us. And, we are excited that local school systems will select the reading assessment tool they prefer for next school year as we confront the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis together.”

Why do diagnostic assessments matter for students?

Mariah Morris, 2019 Burroughs Wellcome Fund North Carolina Teacher of the Year, who has taught various elementary grades including kindergarten and second, said her instructional approaches for each child were based on assessment results. Her interventions depended on how specific those results were.

If a student could read fluently but wasn’t comprehending the text, she might be in a small group working on answering inferencing questions. A student at the same comprehension level could need something completely different. Morris would see this student scored low on phonemic awareness and phonics — how certain letters make certain sounds. She can make her way through text by the words she’s memorized, but can’t decode a word she hasn’t seen before. So this student would be in a small group receiving an intervention working on phonics and phonemic awareness.

“To me that was the really big part of assessment, was how to build instruction and then how to target my interventions so that we could identify students with higher needs,” Morris said.

Vernon-Feagans said some platforms provide more guidance than others on how teachers can adapt instruction to students’ results.

“Assessment plays a really good role as long as assessment helps teachers be able to perform better instruction with their students,” she said.

In order for districts to choose which assessment is best for them, they should ensure the assessment aligns with learning standards, Gehsmann said. She said letting districts decide gives up some control over this alignment. When information is used for shaping instruction, as well as for accountability, she said the assessments need to be reliable — or consistent — and valid: “Does the test actually test what it’s intended to?”

The state should analyze its approved assessments for these properties, she said.

“Assessments that are used for school and district accountability, and those used to make high-stakes decisions about children’s instructional programs, including whether they are promoted to the next grade or retained, must be held to the highest standards of quality,” Gehsmann said in an email. “This includes psychometric properties such as reliability and validity for the populations being assessed. They must also be systematically examined for bias.”

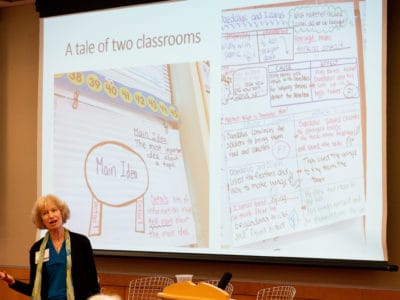

Both Gehsmann and Vernon-Feagans said the assessment platforms the state has used in the past to meet the state’s Read to Achieve requirement don’t provide enough information for teachers to help readers having difficulty. They described these assessments as universal screeners instead of truly “diagnostic” assessments.

Read to Achieve, which has directed more than $150 million to improve stagnant student reading outcomes, requires the State Board to provide districts “with valid, reliable, formative, and diagnostic reading assessments” to test K-3 students.

A Friday Institute for Educational Innovation study in 2018 found the program to have no impact on reading proficiency. In 2018-19, 57% of third graders scored proficiently on end-of-grade reading tests. Proficiency rates varied widely by district.

In 2019, the State Board adopted a strategic plan in a new effort to improve reading scores. Gehsmann served on a task force that was created as part of that plan. The State Board Literacy Task Force was tasked with creating recommendations on improving K-3 reading instruction across the state.

One of those recommendations, adopted by the board last week, directly addresses assessment and adds the “screener” terminology:

“Identify, fund, and implement a valid and reliable literacy screener or diagnostic that aligns with the current science of reading and administer to all K-3 students and to fourth and fifth graders who are below grade level in reading.”

In an ideal world, Gehsmann and Vernon-Feagans said, schools would use a K-3 screener for all students, then use additional diagnostic tools to examine struggling readers’ needs further.

“[A universal screener] clearly does identify those kids who are at-risk, but it often is not detailed enough to really help teachers understand what is going to help that individual child,” Vernon-Feagans said.

Vernon-Feagans said the diagnostic tools that do determine appropriate interventions for struggling readers are often expensive, and school districts have a range of resources to afford them. She said additional diagnostic tools usually are used for children who are at-risk for special education, but that there is a much wider group of students who could benefit from these tools.

“They try and do that for kids who are at-risk for special ed and so forth, but there are just so many more kids that, I hate to say, but they just don’t get good instruction and so they don’t learn how to read.”

Morris said the process of teaching children to read looks very different depending on the income level of the school’s community. She said teachers in a low-wealth school often spend most of their time and energy doing intensive interventions with small groups. Meanwhile, students who are at or above grade-level are doing self-led work. Her experience in a wealthier area was completely different: Students were more likely to be on grade level, and she could spend her energy on providing quality instruction to the entire class.

“It really affects the type of education our students are getting,” Morris said. “… I think that’s a deep equity problem with how we have set up our classrooms and relied on our classroom teachers to do all of these interventions.”

As important as curricula, assessment, and intervention programs are, Morris said, her top concern is the need for more personnel in classrooms, such as reading coaches.

“We know the science of reading can help students from all different backgrounds read proficiently, and we know that’s a weakness in our classrooms, but we’re not going to get there unless we have personnel devoted to help implement it in the schools,” she said.

Editor’s Note: Patrick Miller serves on EducationNC’s Board of Directors.