Experts in children’s health are worried about the COVID-19 ordeal’s potential effects on young brains. Especially in the earliest years of children’s lives, research has shown that traumatic experiences greatly affect how children relate to others, process emotions, and respond to stress.

These behaviors and skills are called different things in different contexts — mental health, social/emotional health, social/emotional learning. They are also measured differently in varied settings like doctor’s offices, child care centers, and elementary schools. A new report from the NC Early Childhood Foundation suggests that the state develop “population-level” measures for children’s social/emotional health, to inform decisions on the supports that children need.

Although different sectors may collect information on individual children, there are no streamlined processes or aggregated measures to see trends across populations of children.

“Without that state level data or county level data, the policymakers or the folks who can actually allocate resources for the state will not be able to tell where the needs are and won’t be able to allocate resources accordingly,” said Mary Mathew, the organization’s collaboration and policy leader.

Mathew said this is new work, not just for the state, but across the country. The report makes recommendations for measuring health of children from infancy through 8 years old.

Here are some key takeaways:

Measuring not just children’s health, but systems that affect it

“We didn’t want the emphasis to be on blaming kids and families for their children’s social/emotional health when we know that that is really a function of the systems that support children and families,” Mathew said.

That’s why the report is split into two categories: measurements of the systems affecting social/emotional health of children and families, and measurements of the skills and processes related to children’s social/emotional health.

“We’ll have the biggest impact if we can actually change the systems that are supporting social/emotional health, so we need to include measures of the systems,” Mathew said.

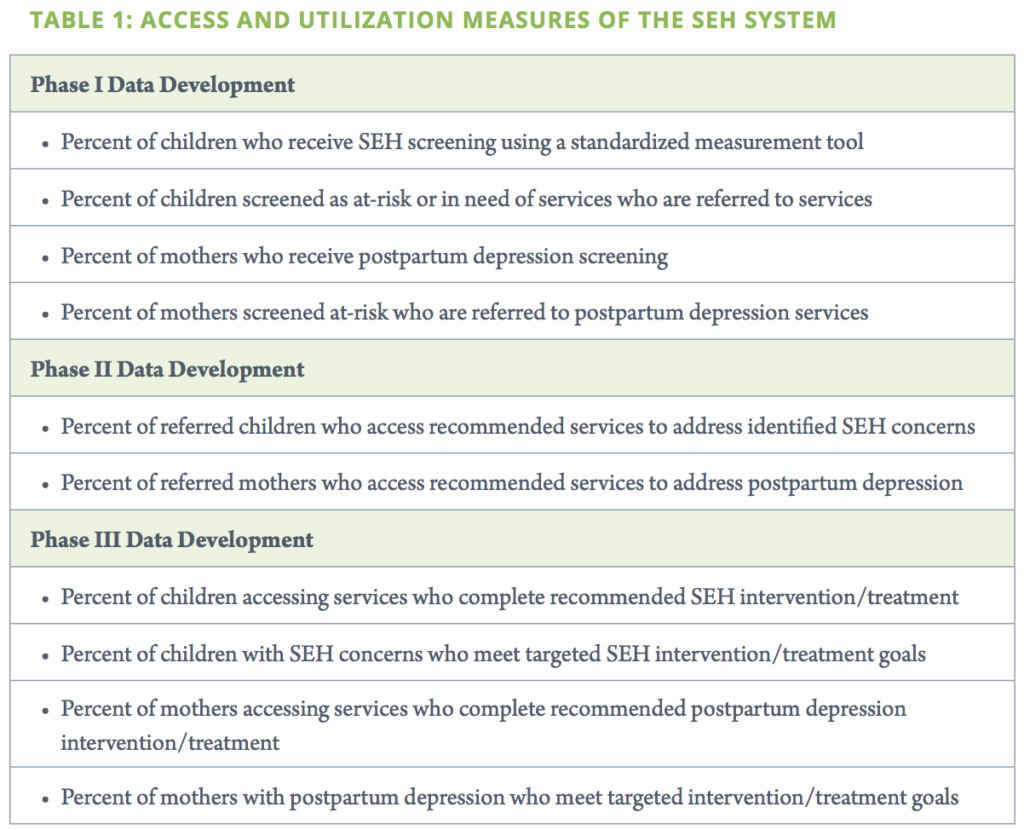

The report starts with recommending measurement of children’s and families’ access to the “social/emotional health system,” looking at screening, referrals, and interventions for children with concerns. The specific data points the report recommends tracking are below, and often include a two-generational approach, looking not just at children’s access to social/emotional services, but at mothers’ access to postpartum depression services.

“You can’t really understand children’s social/emotional health without also understanding a little bit about how the parents are doing because parents are such a critical relationship in that child’s life, and they’re going to directly impact how their child develops their social/emotional health skills,” Mathew said.

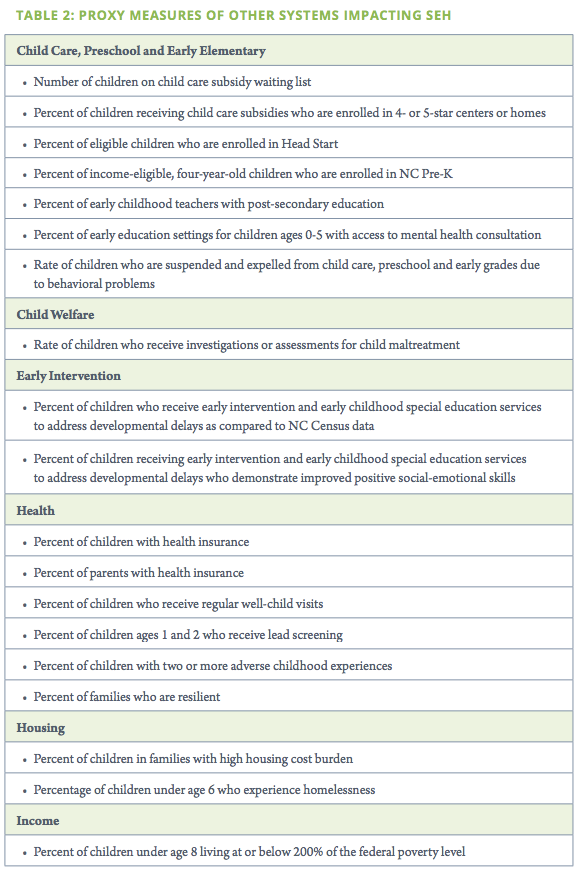

Still in that first “systems” category, the following are “proxy measures” of other systems affecting children’s social/emotional health, such as children’s and families’ access to early education, health, and housing.

Now for directly measuring children’s health

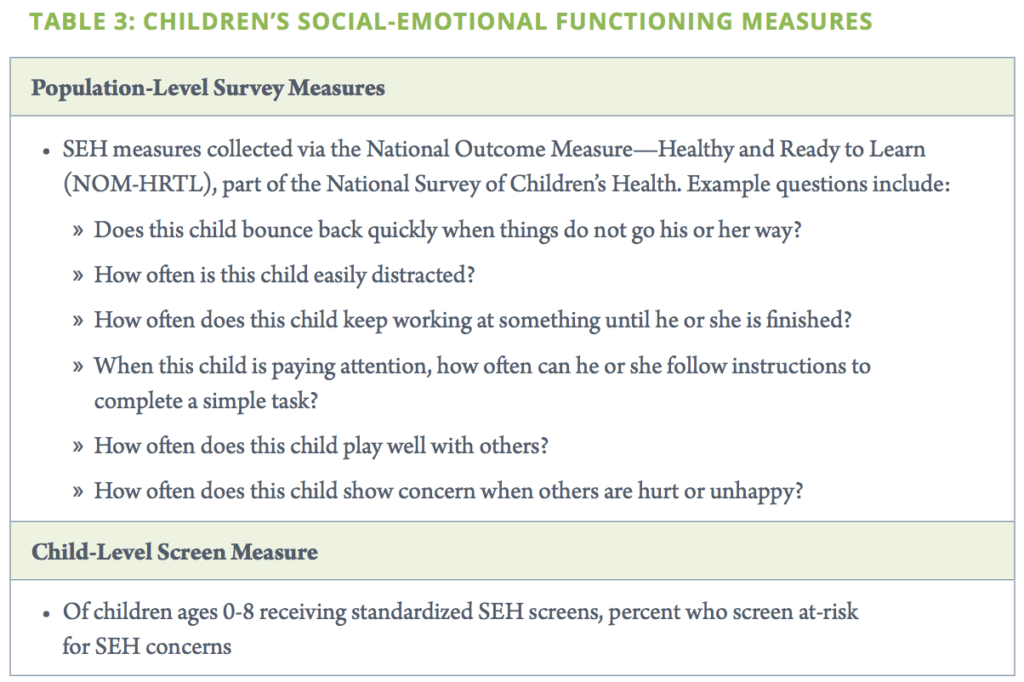

The report recommends collecting information on children’s social/emotional functioning in two ways: through population-level surveys, and through aggregating child-level screens.

For the population-level survey, the report points to the National Outcome Measure — Healthy and Ready to Learn (NOM-HRTL), which is part of the National Survey of Children’s Health.

A Child Trends study in April of the measure described it as unique because it is parent-reported and designed for population-level estimates rather than child-level decision-making.

“Once refined, state-level estimates can be generated regularly, allowing state policymakers to use HRTL data to understand the status of young children in their community,” it said.

The study also found the measure is “a pilot measure and requires additional validity work (e.g., predicting later academic skills) before its full promise can be realized.”

For aggregating data from child-level screening, the report recommends considering the feasibility and cost of aggregating varied information across sectors, and piloting the use of more validated screening in places that don’t already screen. The most common setting for child-level screening is at primary care doctor’s offices, Mathew said. She said the state should start there but implement screening tools across systems that children and families navigate.

The report specifically mentions that the social/emotional questions from the state’s Kindergarten Entry Assessment should not be aggregated. The Department of Public Instruction is rolling out changes to that assessment, now called the NC Early Learning Inventory, including integration into the Teaching Strategies Gold platform.

“Further investigation is required to determine if aggregate reporting is an

appropriate use of Teaching Strategies Gold (TS Gold) data,” the report says.

Ability to disaggregate measures by race

The report calls on state leaders to use measures that can be disaggregated by race and ethnicity “so that we could be ensuring equity in how the resources are allocated,” Mathew said.

Ensuring that children of color are represented fairly is a thread throughout the report, which suggests that an equity lens be applied to the processes and questions that are used to gather information about children. Mathew said racial bias not only can affect how the person assessing the child records information, but is often baked into the questions themselves.

“It’s … a certain kind of validity or measuring the thing that it’s intended to measure that a lot of screens don’t have yet because they’ve been primarily normed on white kids,” Mathew said.

The report says its findings are meant to inform The NC Early Childhood Action Plan and NCECF’s ongoing Pathways to Grade-Level Reading initiative. The report is also aligned with a cross-sector effort led by NC Child and focused on improving social/emotional health systems for children and families — called NC Initiative for Young Children’s Social-Emotional Health.