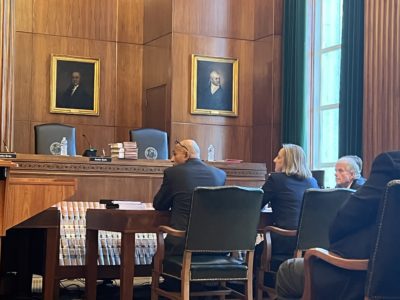

In the oral arguments on Feb. 22, 2024, in the ongoing Leandro litigation, the question before the N.C. Supreme Court was narrow.

The discussion, however, was far-ranging and broad.

The justices and attorneys revisited fundamental parts of the 1997 and 2004 Leandro opinions along with the extensive proceedings from Judge Howard E. Manning’s courtroom. This is all in addition to the issue at hand: whether the trial court had subject matter jurisdiction to issue the April 17, 2023, order holding the state responsible for the deficit in funding for the State’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan.

Leading up to hearing, the Supreme Court has issued a series of opinions, beginning in 1997, holding that students have a constitutional right to a sound, basic education and that the State is obligated to “guard and maintain that right.”

In the 2022 Leandro IV decision, the Supreme Court affirmed findings of a statewide constitutional violation and the appropriateness of the remedy of the Comprehensive Remedial Plan developed by the State and Plaintiff parties. It also held that the trial court had the authority to enforce the plan, including directing state officials to direct surplus funds to make up for the deficit in the budget passed by the General Assembly. The Supreme Court remanded the case to the trial court to recalculate the funding deficit based upon the most recent State budget. The legislative Defendant Intervenors appealed the order issued by the trial court, arguing that the trial court lacked subject matter jurisdiction for its April 17, 2023, order.

Here is an explanation of the different parties to the case.

The oral arguments

In the oral arguments, Matthew Tilley, on behalf of the legislative Defendant Intervenors, argued that the Plaintiff school boards did not have standing for a statewide remedy as the violations were related to district-specific conditions such that they could not possibly represent the interests of school boards not included in the lawsuit.

Justice Trey Allen took it a step further, questioning whether school boards had standing to represent students. Referring back to the 2004 Leandro II opinion, attorneys for the Plaintiffs and the State emphatically replied that the Supreme Court had determined that the school boards could represent students. The State went on to note that while the State had been the one to raise this question, they have relied on this holding for twenty years.

In another part of the wide-ranging discussions, Justice Allen, along with Justice Richard Dietz, questioned whether the state was responsible for actions at the local level. Another basic tenet of the Leandro holdings, Plaintiff attorney Melanie Dubis replied, “The Court very clearly stated [in 2004 Leandro II] that the State cannot abdicate its constitutional responsibility by blaming the local education authorities. That is very clear.”

The Court went in another direction with a line of questions by Justice Richard Dietz.

Justice Dietz posited: “There’s a group of students who’ve never heard of Leandro, who have no idea this case exists or anything about it, but they’re not getting a sound, basic education in their school. They get together with their parents, they get a lawyer, they get experts to explain what needs to be done to fix their school so they can get a sound, basic education. And they go to court and they file a lawsuit. What’s going to happen to that lawsuit? I just want to know. What will those parents be told by a trial judge? ‘Sorry your rights have already been decided’?”

Justice Dietz continued, “Or can there continue to be many, many more Leandro suits?” If there were more lawsuits, he expressed the concern that there would be conflicting orders. He later searched for a resolution: “So why couldn’t we do the same thing with procedural rules about a lawsuit, create a multi-district litigation process or create a streamlined class action system?”

As courts will do, they entertained various hypotheticals of the reach of the Leandro litigation. Justice Allison Riggs and Justice Anita Earls asked the Defendant Intervenors attorney Matthew Tilley: if every school district joined in a lawsuit in order to meet plaintiff standing, would the judiciary have the authority to enforce spending? When pressed, Tilley said that the court would have authority under the 2022 Leandro IV decision — the decision he sought to reverse.

Plaintiff attorney Melanie Dubis raised the hypothetical of what a Hoke County only remedy would look like. “We have schools of public education across the State in our university system. Does the State dictate that the first 114 graduates have to teach in Hoke County [to address the 114 classrooms without a certified teacher]? Do you provide scholarships across the State to high school students, but they only get the scholarships if they commit to teach in Hoke County?”

Dubis continued: “It seems like we’re not achieving what Leandro instructed that we need to achieve here, which is to get to one comprehensive solution…. We would expect that the other counties who have classrooms not staffed by certified teachers will file their lawsuits…. How do we deal with that? Whoever gets the courthouse first?”

Solicitor General Ryan Park, representing the Executive Branch of the State, seemed to search for some possible concessions. If having student representatives as plaintiffs is a true concern, Ryan said, “we can move forward with that as the rule of law and on remand, and I’m sure that Plaintiff’s counsel can cure that defect.” He concluded his comments, “We welcome the General Assembly’s continued participation in this lawsuit. We welcome this Court’s guidance on how we can proceed here to vindicate the constitutional rights of the people’s children.”

Subject matter jurisdiction

At the heart of this hearing is subject matter jurisdiction: the authority of the court to hear evidence, make findings, and rule on issues before it. Justice Phil Berger, Jr., who wrote the dissent in the 2022 Leandro IV decision, focused his questions on a prior court opinion that holds that a court may address subject matter jurisdiction at any time. He highlighted High v. Pearce, a 1941 North Carolina Supreme Court opinion, that held “Where there is no jurisdiction of the subject matter the whole proceeding is void ab initio and may be treated as a nullity anywhere, at any time, and for any purpose.” The opinion was not included in the briefs submitted by any of the parties. When asked by Justice Berger, the State’s attorney Paul Ryan agreed that it was still good law.

What do the oral arguments suggest about where the North Carolina Supreme Court may land?

We heard from five of the seven justices in the oral arguments: Chief Justice Paul Newby and Justice Tamara Barringer did not ask any questions or make comments. They did join Justice Berger’s dissent in the 2022 Leandro IV decision.

Some on the Supreme Court seem poised to overrule Leandro IV and the question may be whether the majority of the court wants to apply a surgical scalpel to the opinion or eviscerate the Leandro rulings, digging deep into fundamental constitutional principles.

Justice Dietz seemed to be suggesting a middle ground: some sort of remand to address concerns and cure defects. If this doesn’t make its way into the majority opinion, Justice Dietz may write a concurring (or dissenting) opinion suggesting a way forward with constitutional litigation.

Partisan courts in 1997 and 2004 were able to come together to create unanimous Supreme Court opinions.

The constitutional rights of children may be at stake in this case, but for many the politics of the Supreme Court are on trial as well.

Correction: This article was updated to reflect the correct title for Solicitor General Ryan Park.