This is Part Two of our series on learning differences. In Part One, EdNC reporter Rupen Fofaria shares his learning differences story. In this installment, we take a broader look at what “learning differences” means.

There’s a boy in his reading class that doesn’t have his nose pressed in a book. His peers all have the spines of their textbooks split and are turning pages, some tracking words with their fingers. But this boy is sitting at his desk, headphones fastened tightly on his head, listening to the words read to him by a narrator.

He has a medical diagnosis called dyslexia that makes reading much harder for him than most. To receive the accommodation of audio books — an accommodation necessary to level the learning field for him — he has received a legal designation called a specific learning disability that set him up for an Individual Education Plan (IEP).

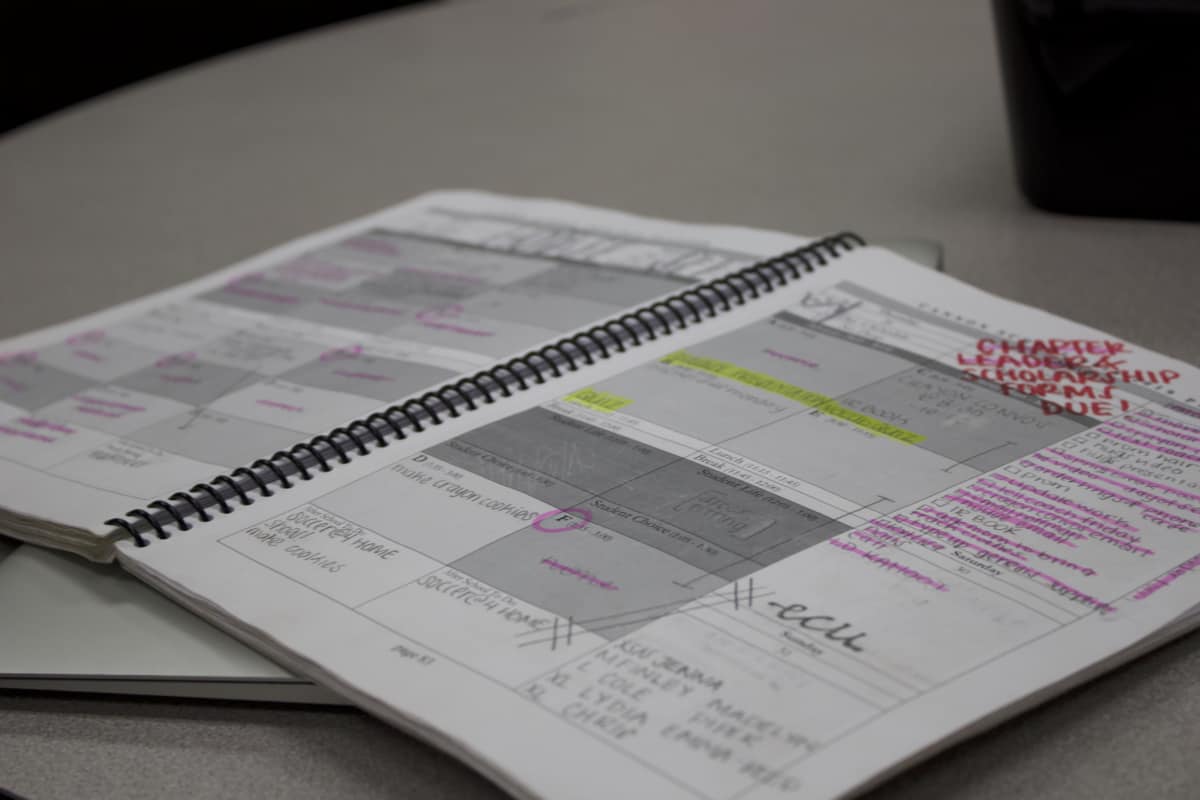

Nearby, there’s a girl who is scribbling away in a weekly planner, breaking down a number of tasks within the project her teacher just assigned. Around her, classmates are already waist-deep in the same project, doing research or starting to write thoughts. She doesn’t have a medical diagnosis, nor does she have a legal designation. Yet, she experiences a debilitating moment after large projects are assigned. Without the planner, guidance on how to break down the assignment, and tricks such as color coding and categorizing, she simply can’t get started.

The details of these stories may be different, and only one story stamped with a legislative seal of approval, but both students share the experience of feeling lost and confused at school when they are asked to perform in the same method and manner as their peers. Their brains just work differently.

These are learning differences. According to studies, roughly 1 in 5 students in America have them and are prone to academic, emotional, and social struggles as a result.

“Complete confusion is the way that I remember the world,” said David Flink, who identifies as dyslexic and ADHD, and founded a mentoring organization called Eye to Eye that pairs young students with older ones who share learning differences and have mastered tools that help.

“Actually, there were two worlds. There was the world that happened in school and there was the world that happened outside of school. The world that happened out of school made a lot sense to me because there were things that I could do — like do your chores, go play outside with your friends. They were things that many kids have the opportunity to do, and I could do and do well.

And then, I would go into school and there were things that were asked of me, and I just couldn’t do those things. And I couldn’t understand why. I would look around the classroom and the teacher would say something like, ‘Read these instructions and do this assignment.’ I just couldn’t do that. And I didn’t have a word or explanation for it.”

Abundance of terminology

Today, there are myriad umbrella terms for what Flink was experiencing. And sometimes, the bevy of terms can lead to confusion.

You’ve probably read about learning disabilities and their various subcategories like dyslexia or dysgraphia. Whereas learning disability is a legal term, specific conditions like dyslexia or dysgraphia — or attention issues like Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which isn’t legally a learning disability — are medical diagnoses. You might have also come across phrases like learner variability, learning sciences, or even learning differences.

The latter three are neither legal nor medical in genesis. Sometimes they are used for specific diagnoses, while sometimes they refer to the same or overlapping spectrum of conditions.

So, what is the proper terminology?

What’s most important, say those who dedicate their careers to studying student learners, is that we not confuse one term as a euphemism for another, and that we not get so bogged down in terminology that we lose sight of the greater picture.

“There are going to be readers out there, for sure, who are going to think that we really mean learning disabilities and we’re saying learning differences to be politically correct,” said Alex Dreier, an Instructional Design Lead at N.C. State’s Friday Institute for Educational Innovation. “They are two distinct things. This is not a politically correct way of referring to dyslexia.”

Dreier and his colleagues use the term “learning differences,” which encompasses specifically-diagnosed learning disabilities and attention disorders, but also includes areas of executive functioning, like task initiation and working memory to help the wider population of students who can succeed if only they are reached in a manner that is compatible with the way their brains work.

And reaching these kids, identifying them, and getting them help, Flink says, is much more important than the terminology used.

“I think it’s okay that we use broad terminology — but that it then connects to experiences,” Flink said. “Let’s not be afraid of the words. So whether you choose learning disability or learning difference, and one is more of a social construction and one is literally a term that we use for legal recourse at schools, it’s really easiest to understand this as brains are just hardwired in different ways. One in five people in America have a hardwiring that makes it difficult for them to do things like read and to work with numbers.”

Or get started on tasks. Or organize material. Or hear instruction verbally. Or process certain sounds, connect different ideas, or hold their attention in one place for very long.

Learning differences come in so many forms, but the way to understand them appears less to deal with having a correct name for it than in trying to relate to the experience a particular student is having.

“I think it’s really the job of each of us with our own labels and our own journeys to try to make these things real,” Flink said. “It just comes down to really simple words, really simple language, and grounding it with experience.”

In fact, not only does Flink refrain from focusing on diagnoses, he chooses not to use the word diagnosis.

“I call them identities,” he said. “I have a diagnosis of ADHD and dyslexia, but I identify as a person with dyslexia and ADHD. I think that allows me to communicate with people that don’t have that label what the world looks like for me.”

Focusing on the learner

The idea of focusing on the learner is especially important, because the underlying condition — the wiring of the brain — is hidden from sight. So, unless a student or an advocate speaks up, a child’s difficulty in task initiation can look like procrastination, and dyslexia or ADHD can look like lack of discipline, and working memory issues can look like lack of focus or effort.

“I think with a lot of kids and teachers who aren’t ever exposed to this sort of thing, it’s sort of the misattribution of behavior,” Dreier said. “So you have a symptom of something and you have to identify the root cause. It’s not the kid is bad, the kid is lazy, or the kid is unmotivated, or anything like that.

It’s maybe the kid doesn’t have the self-awareness to be able to know: here are the things that I need to be able to initiate this task or to be able get what I need in the classroom.”

For instance, a student may take much longer to read than their peers and still not be able to pick details out of a passage. You watched them sitting there, staring at the page, and you know they know how to read. It may seem like this student simply was not focused during reading time and should be more disciplined to stay on the reading task.

But to a student with dyslexia, it might take much greater concentration, leading to a slower pace and a higher rate of fatigue. Also, the words might feel like they are jumping around, and in some instances what they make out is nonsensical.

Imagine for a moment that you were watching yourself reading this right now. From seeing your hands hold the device and watching your eyes dart back and forth over the lines, you wouldn’t know what was happening in your head. Reading is being done; progress is being made. But what if the screen didn’t look like it does right now? What if it looked more like this? Simply by seeing yourself holding the device and squinting at the screen, how would you know what the reader is experiencing?

We can’t see all that is happening in the student’s mind, so unless it is communicated, failure to finish on time or comprehend passages could easily be mistaken for focus or behavioral problems.

“If you’re really trying to uncover why someone isn’t understanding math or why someone isn’t learning these other things, and you’re trying to do that without really understanding the learner, I think a lot of times we sell it short,” said Mary Ann Wolf, director of the Professional Learning and Leading Collaborative at the Friday Institute, “You say, ‘Oh, they just don’t get fractions.’ Well, that might be true for one kid, but a lot of kids have these other challenges.”

Trouble coping like the majority

“Ultimately, I think people find understanding when they just relate to other people,” said Flink.

And that’s what Wolf and her team at the Friday Institute try to do when they reach out to teachers or parents who engage with the 1 in 5 students who has a learning disability, but who themselves are part of the 4 in 5 that may not understand what a learning difference feels like.

“You say kids don’t have study skills or that they don’t get their homework done and they forget it. Even if you have a learning disability diagnosed, ADHD or whatever that might be, you still have a challenge of executive function,” Wolf said. “If you’re trying to make this real for people, almost every parent, every teacher, every administrator has that connection to when that’s hard for them and when that works well.”

Sometimes, experts say, making a learning difference relatable is helpful to gain understanding from a teacher or parent who hasn’t felt any of the cauldron of emotions an LD student has internalized. The parent or teacher may relate better by considering times they had trouble organizing major projects or remembering where they left their keys.

On the other hand, relational discussions may minimize the challenge of learning differences, prompting some to wonder why this is a big deal for the few if many deal with procrastination and many deal with organizational challenges. Why should we make accommodations for certain students?

“I think the difference is most of us figure out coping skills on our own,” Wolf said. “But there’s 1 in 5 who may need more support. And even the ones that figure it out on their own, [that] doesn’t mean they’re figuring it out in an effective way.”

Being receptive to the student who needs the help, then, is imperative. Yet, the possibility that calls for help might be mistaken for students looking for shortcuts exists. And it is unique to this type of incapacity or hindrance because the root cause is hidden from plain sight.

Indeed, some parents have counseled their children to keep their learning differences secret so as not to negatively prejudice them at school, in fear that a teacher will question the validity of their child’s needs or that other students might make fun.

“If your kid had a physical disability, let’s say he was in a wheelchair, you wouldn’t tell your kid, ‘Don’t tell anyone you’re in a wheelchair,’” Flink said. “He’s in a wheelchair, it’s obvious. So your kid’s going to need to ask for a ramp when they get to a building that has steps. That’s what they need to do to get into the building.

And if your kid has dyslexia, they’re going to need to ask for a ramp to get into that book. They’re going to need to do that. But the only way you can explain why the ramp into the book may be listening to it rather than reading with your eyes is if you say, ‘Hey, I’m dyslexic. I read better with my ears than with my eyes.’”

And with advances in neurosciences, there are a number of ramps that have been developed for students with learning differences. As we’ll explore deeper in future articles of this series, these can range from providing audio books and large print texts, to allowing verbal responses, to the use of a laptop, or allowing more frequent breaks or extended time to finish assignments and exams.

Without the ability to change their own brain wiring, these accommodations are necessary for students with learning differences to have an equal shot at academic and future success as their peers.

“The ramps that these kids need are not cheating,” Flink said. “I think that’s the biggest fear that teachers have. Like, is it okay that I encourage my dyslexic student to use audio books? Is that going to give them a disadvantage later on? So teaching the teachers where the resources are and that they are okay to use — that, alone, can be game-changing for teachers.”

But, as we will explore in our next series, perhaps the greatest resource available is the student’s own voice. America’s education system is relatively young, and, as it exists today, still very much a product of the Industrial Age. But everyone has their differences, so assembly-line instruction — though perhaps effective for many — will not adequately reach all. In recent years, there has been a greater push for more personalized learning. But no matter what response is utilized as a resource to meet each child’s need, there must first be a call for that response.

“I don’t think personalized learning is the silver bullet,” Flink said. “I don’t think there is a silver bullet. And, let’s say that personalized learning gets the kind of traction I think we’d all love … I still think you need to move in a direction of personalized learning while simultaneously move in a direction of education identity formation.

Kids need to know how they learn and think best in addition to a system that is responsive to that. So personalized learning is the responsive part, but kids need to also … articulate how they learn and think best so that a world in which schools can be responsive to that can function well.”

This is Part Two of our series on Learning Differences. To read Part One, click here. In Part Three, we will explore what learning differences look like in the lives of different students — some who are currently in school and some who have navigated their differences to successful lives.