There used to be a dress code at SouthWest Edgecombe High School (SWEHS).

As students entered school each day, it was more about worry than welcome. Worry about drugs and weapons — and the dress code.

Now, students come as they are and are greeted with love first.

Meet Lauren Lampron, the principal who changed all of that and more.

The students nicknamed her L Money — because she is cool, admitting with a laugh that she asked them for the nickname. She even has a personalized handshake.

This is a high school where each of the 807 students is seen and known as the person they are and can be.

So it makes sense that the principal is too.

The day we visited SWEHS, someone spray painted the N-word on the football field. Lampron moved into high gear to have it removed before students could see it.

The next day, she held a circle with the football team, administrators, the school resource officer, and coaches. They talked about what it felt like to have their safe space violated, what it meant from their individual vantage points, and how to move forward.

Lampron said, “The players spoke beautiful words of encouragement and purpose. They did a ‘breakdown,’ putting their hands in and breaking down on ‘family’ on the count of three.”

“We are going to anchor in talking about our hurts and making it safe to share our truth with mercy,” she said.

And for another day, the school she works so hard to make feel welcome to all continued to feel welcome to all.

Dropping the dress code

When Lampron started at SWEHS, she looked at suspension data and noticed how many suspensions were attributed to violations of the dress code — a dress code, she noted, that was informed by white, middle-class values.

She conducted an equity audit of herself as she greeted students in the morning.

She tallied who she said good morning to and who she greeted with a correction. “The kids who looked like me got all of me. But I heard myself saying over and over to the kids who didn’t look like me, ‘my expectation is that you take your hoodie off in this building.'”

She realized the dress code created opposition from the very beginning of each day. “It felt to them like we don’t understand them, we don’t see them, we don’t value them,” she said.

Lampron wanted to build a school community that welcomed the whole child.

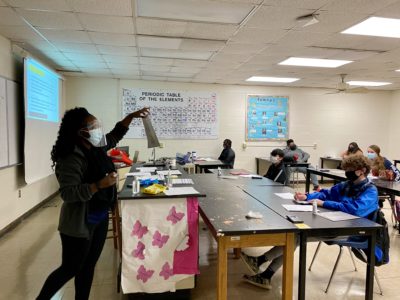

She showed the data to her teachers and then she conducted an equity audit of how teachers greeted their students as they entered the classroom.

It was clear why her Black and Brown students didn’t feel welcome.

The students asked Lampron, “Why do you care if I wear a hoodie? Are you scared of me when I wear one?”

“Why are hats OK and hoods aren’t?” Lampron asked herself.

She made a deal with the staff. No dress codes for students or staff. If teachers can teach wearing whatever they want, then students can learn wearing whatever they want, she reasoned.

Lampron believes educators have to honor and meet students where they are to have a shot a guiding them where they are going. Her number one goal for herself is to get kids in the door of the school.

To have the conversations about building resumes, how to show up at interviews, and the importance of soft skills, she said you have to first have a relationship with the student, and that only happens if they are in school.

“These students,” she said, “are anchored in a high school body with high school social media and high school norms. They want to look fresh. And I just need to see their eyes.”

Now she tells the students, “My charge is to keep you safe here — physically, emotionally, and mentally.”

That gets them in door to learn.

SWEHS had a school performance grade of C in 2022, its highest grade since 2015, and it met expected growth.

The outcomes of students have to matter more than the intentions of educators

Lampron was an English teacher. She will tell you she doesn’t do math.

But she understands what kids need to succeed. So consider this a lesson in math.

Lampron will also tell you that new principals are told not to change anything for the first six months they are on the job. “Walk around. Get to know the people,” she remembers people saying to her.

She couldn’t do that given all of the barriers she saw for her students to an equitable education.

So hers is also a lesson in leadership and life.

Lampron didn’t like what she saw when she looked at which students in her school were taking and passing Math 1.

Why is Math 1 such a big deal? “Once they get through Math 1, they know how to do the work,” she said. More importantly, four units of college preparatory mathematics are required for college admission, so access to Math 1 is access to college.

Lampron dug deeper, and she realized there was a problem with the master schedule. With the best of intentions, Foundations of Math was being offered to ninth-graders in first semester to ready them for Math 1.

The problem was that if they failed, there wasn’t a math class for them to take second semester. So during the first semester of 10th grade, they would repeat Foundations of Math. Redux in 11th grade.

You see the problem.

These students were in a loop that foreclosed college as an option because of how math was scheduled.

Lampron then diagnosed gaps in student knowledge. For example, Math 1 requires mastery of quadratic equations, and to get there, students have to understand operations of integers.

Lampron moved to close that gap. High school teachers, she said, don’t think they have time to teach operations of integers. “I dare not,” she said, “because we agree that to get to a quadratic function, they need to know how to do this.”

She then partnered with eighth grade teachers for the first time. Her team looked at each incoming freshman’s EVAAS scores. But knowing “kids are more than numbers,” they asked eighth grade teachers whether each student should be in Foundations, retake Math 1, be in Honors, or be placed in Math 2.

They hand-scheduled every incoming ninth-grader.

Now, even if a ninth-grader fails Foundations, the student still takes Math 1 in second semester of ninth grade. If they pass Math 1, they are also given credit for Foundations of Math.

Lampron then took a look at what was happening with students with an exceptional children (EC) designation.

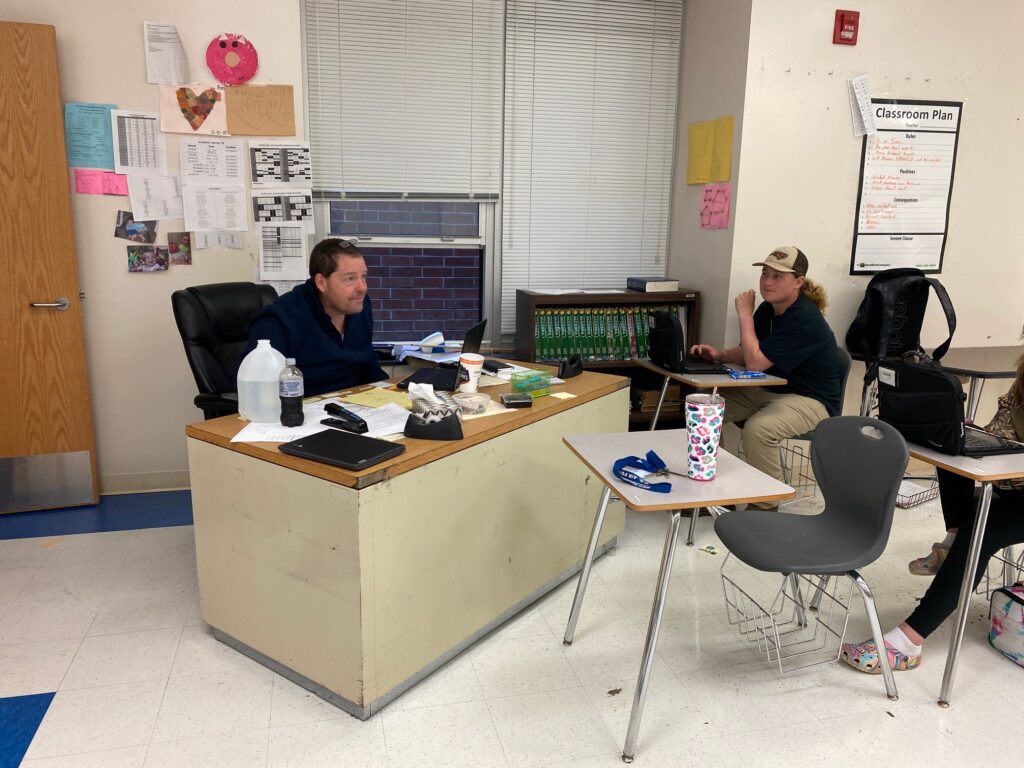

Meet Charles Griffith, who Lampron said is among the best math teachers in the district. She moved him from teaching math to 96 students to serving EC students in classes of 12. She calls it a game changer.

“Those 12 kids are the ones who need him the most,” said Lampron.

A student in his class tells me Griffith knows how to work magic with them, and in fact, last semester, Griffith had a 100% pass rate for all of his students.

Another student tells me he had a lot of bad grades before being in class with Griffith. “Now I am doing great,” he reports. What’s the difference, I ask. “He will actually walk you through a lot of stuff. I can understand him. He takes it slower, but you learn faster,” the student said.

In the first semester of ninth grade, Foundations of Math is offered to these students as an inclusion class. “Griffith is in it with them,” Lampron said.

Then, in the second semester, these students take science in the first block, a learning strategies course in the second block (important for two reasons: It’s the period before math and also the same semester they will take the EOC), Math 1 in third block, and an elective in fourth block.

The planning period for math teachers is fourth block so every student has a second chance to get their math in day-to-day.

Older grades of students never have math in first block so that if they are late once they start driving they never miss math just because they are tardy.

When Lampron got to SWEHS, the schedule had been static for five years. Every year she has been there, the schedule has changed.

“Kids are completely different. Their needs are completely different. We need to design with the children in mind,” she said.

Her team also hand-schedules all students with a 504 or IEP, and all students identified as ESL, LEP, or EC.

“Handing out schedules to me is a labor of love,” she said. “I intimately know you and love you as a ninth-grader, and I’ve never seen you before. But I know your academic testing history. I know your projections. I know the level of support you need.”

All of this required getting the buy-in of the math teachers who do the teaching and the counselors who do the scheduling.

And parents.

“Parents,” Lampron said, “have so often been left out of the conversation.”

Now they know their student’s schedule has been designed with their child in mind, so they trust the process.

In educator speak, Lampron aligned the coherence maps (which show connections between math standards) with the course sequence and master schedule, and provided supports for EC students and the opportunity for tutorials.

This is what adaptive change looks like, said Lampron. In 2022, SWEHS met expected growth in both Math 1 and Math 3.

The importance of student athletes

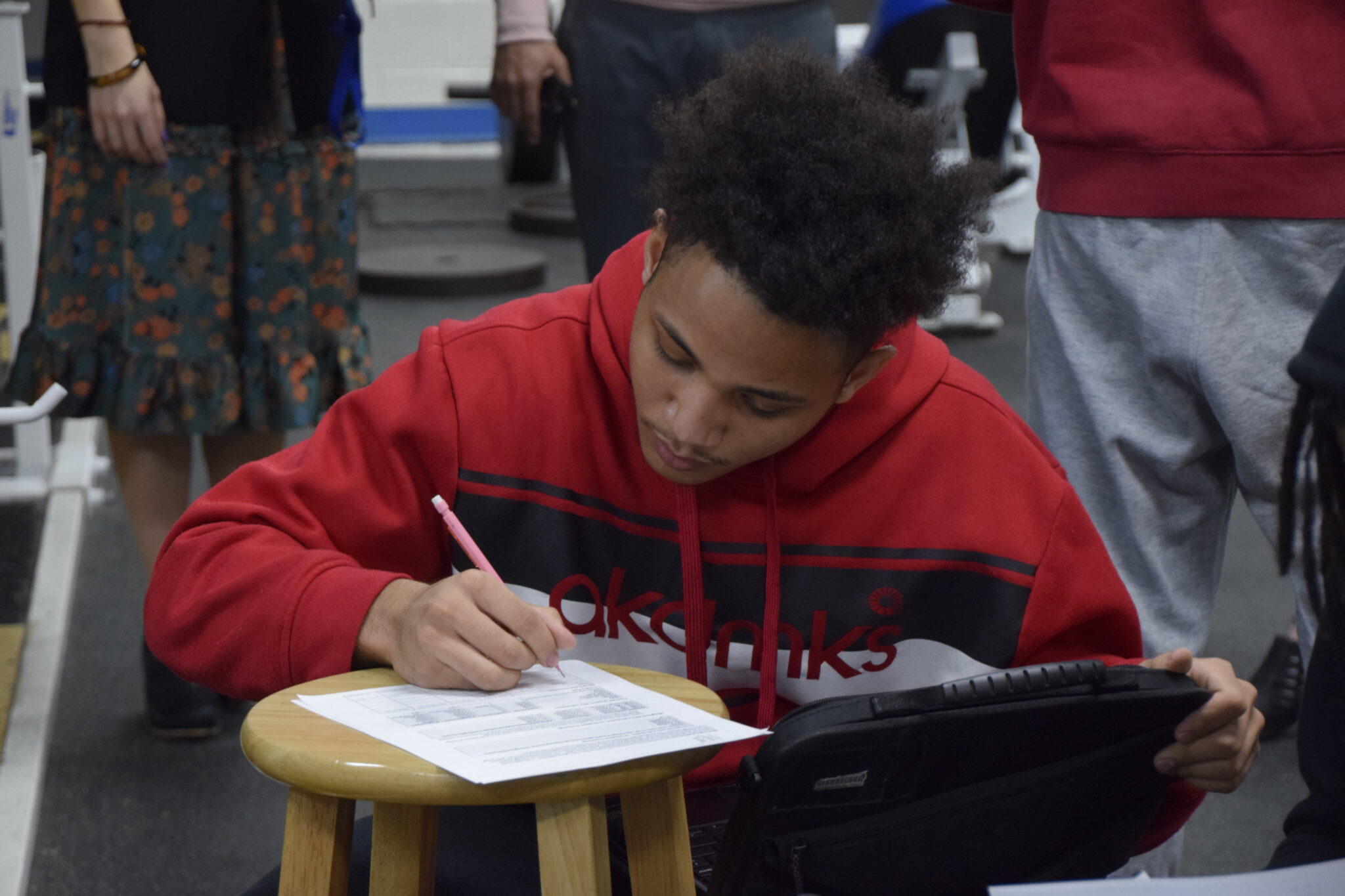

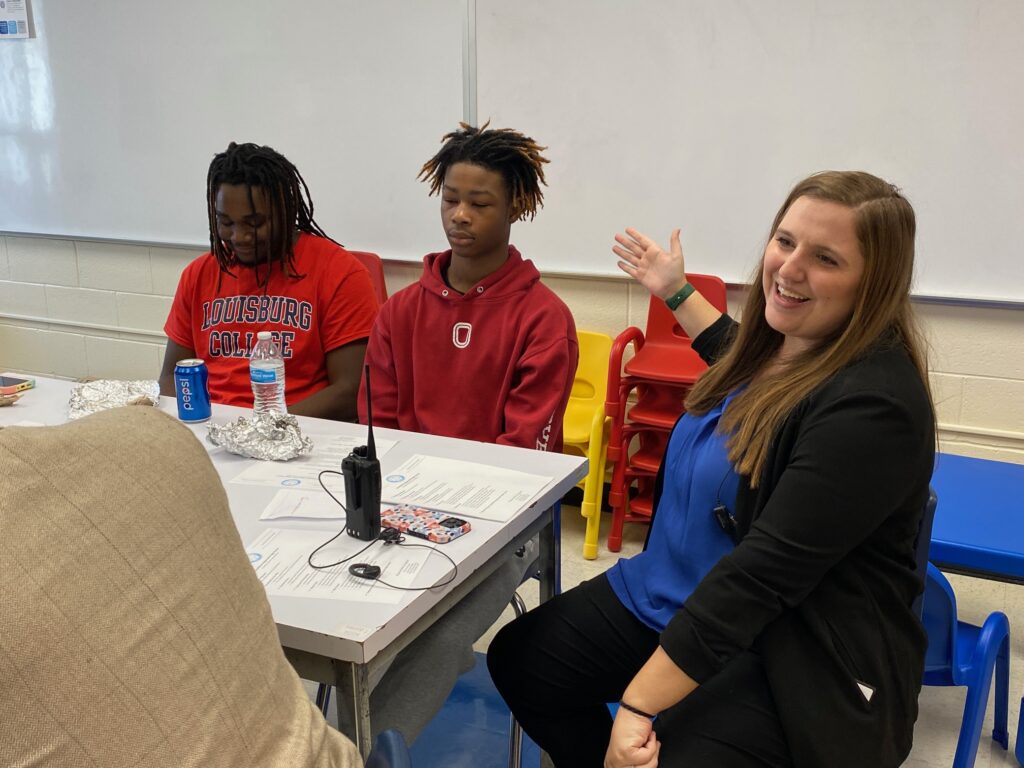

Meet THE Keyshawn Powell, as he is introduced to us by school leaders.

A senior, Powell has a 3.9 GPA and is #8 in his class. He is in the National Honor Society and Beta Club, and he is an Academic All-American. President of the Student Government Association, he just signed to Louisburg College, where he will play football and major in business.

There have been four signing days at SWEHS in the last two weeks — students accepting offers to go to a college to play sports with a scholarship.

“Because we are about the work,” Lampron said.

During POWER — a time during the school day when students Plan, Organize, Work, Eat, Relax — we watched the varsity football coach audit transcripts with student athletes.

Students are taught the value of taking weighted courses.

They are taught the difference between an 88 and a 90, a 3.0 or a 4.0, and how to discern where they can make up extra points as needed.

They look for mistakes in their transcripts and learn how to get them fixed.

The grade point averages of student athletes are posted in the hallways.

One student shared that since auditing his transcript he had moved up from a 1.8 GPA to a 2.4. Last spring, he had a 4.0. Math had been a pain point, but now he is taking Math 3 Honors.

“How many head varsity football coaches know the GPA of their individual players?” asked Lampron.

During that same block of POWER, the baseball team was outside in batting practice because practice was expected to be cancelled that afternoon due to rain.

Student athletes, dressed up in their uniforms, visit elementary and middle schools and are presented and seen as community leaders.

The role of Transcend

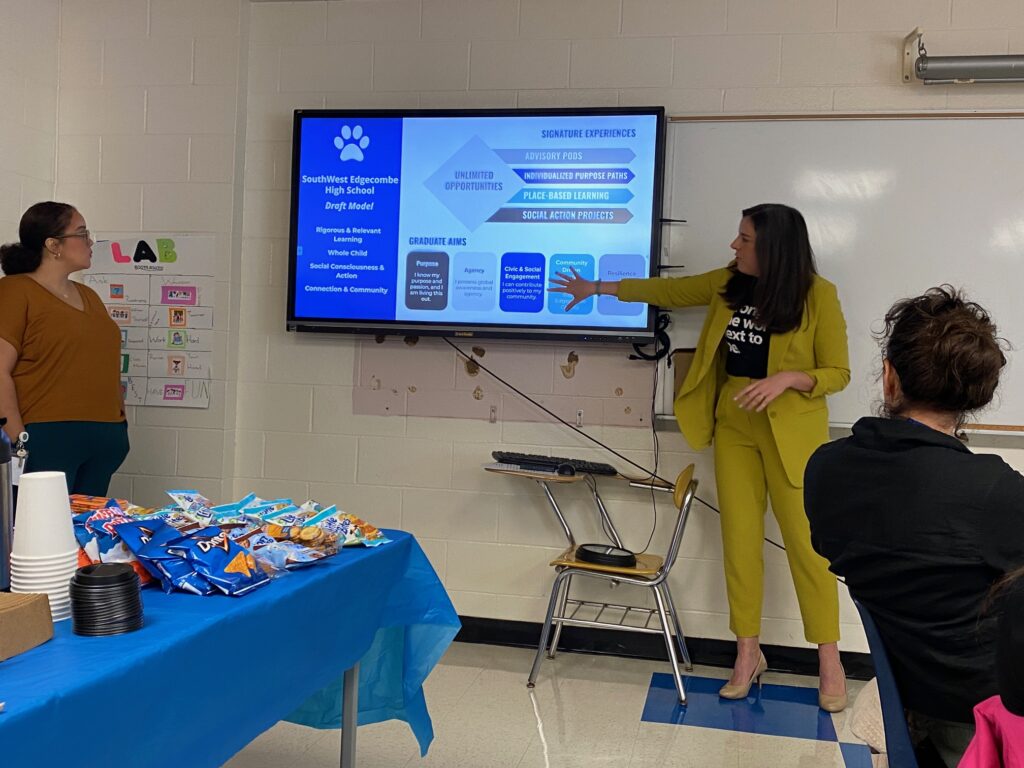

Transcend is a national organization that supports schools and communities “to create and spread extraordinary, equitable learning environments.”

Here is what that work looks like at SWEHS.

The first step is putting together a design team of educators to work with the consultants from Transcend.

Community engagement happens next, including interviews, focus groups, and surveys. For example, at SWEHS, surveys revealed that while 63% of students believe their learning is customized for them, only 39% of students believe the learning is relevant.

Insights from the community engagement are then analyzed and developed, identifying both tensions and where leaps are needed.

Inspiration is drawn from other schools who have tackled similar challenges.

Design sprints are conducted to begin to envision a draft model for school transformation. With feedback from the community on the draft, details are developed before the model is piloted. The pilot informs sustainable school transformation over the long-haul.

At SWEHS, the model includes promoting rigorous and relevant learning for the whole child and supporting social consciousness and action while building connections and community.

Signature experiences for students include advisory pods, the development of individualized purpose pathways, place-based learning, and social action projects.

These opportunities are aligned with the district’s graduate aims, which include:

1. Graduates will know their purpose and passion, and be living this out;

2. Graduates will possess global awareness and agency;

3. Graduates will be making positive contributions to their community;

4. Graduates will create or seize opportunities to return to — or stay — in Edgecombe County; and

5. Graduates will be resilient in the face of challenges.

On learning and leadership

Keyshawn Powell lobbied Lampron to bring students back to school during COVID-19. He wanted school to be better and more enjoyable.

“Let’s learn,” he said to her.

SWEHS was one of the first schools back because of his leadership. And hers.

“She’s the type of principal I want to be under,” he said.

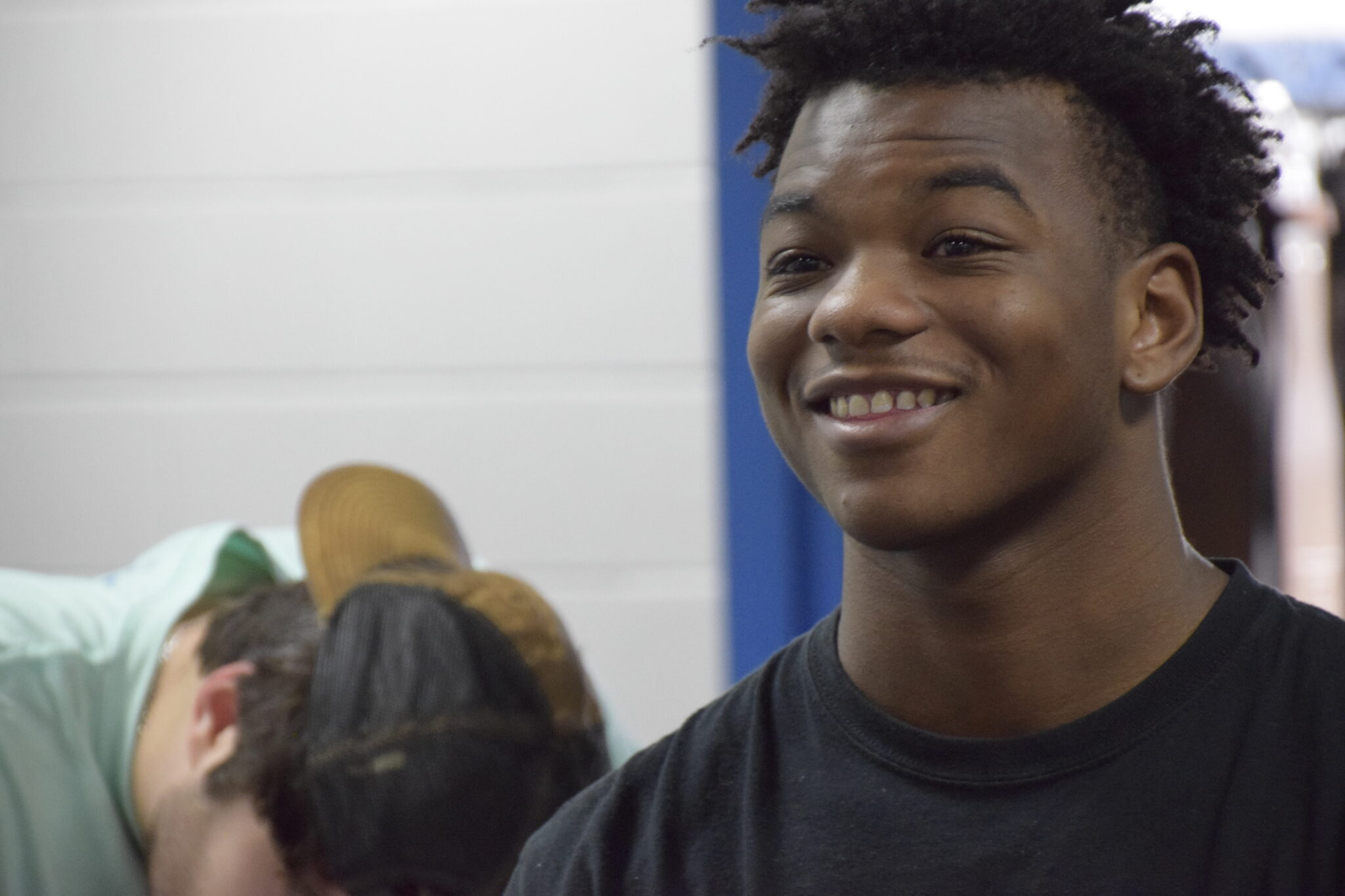

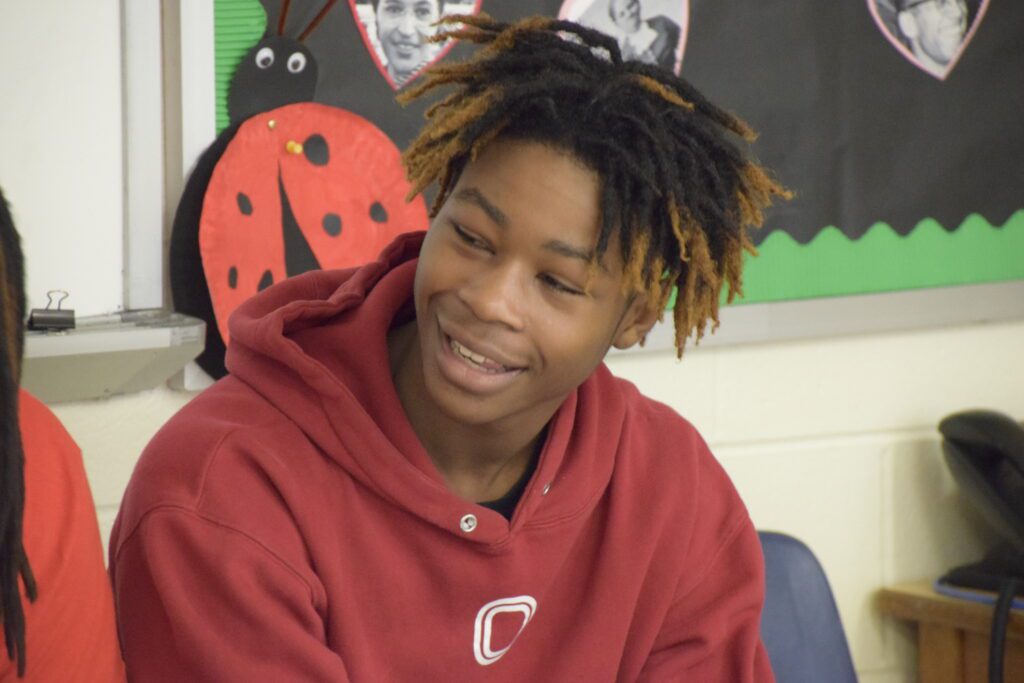

The day we visited SWEHS, we met with this student panel.

Ricky Smith, all the way on the right on the panel, is a freshman. In his early conversations with Lampron, they talked about the transition into high school, meeting new people, growing into the person you want to be, and preparing for college.

Smith went home and reflected on the conversation. He said he took it to heart.

He thought, “I’m gonna go out there and work.”

Lampron moved him into all Honors classes.

They kept talking, and Lampron helped Smith see the difference between being good, great, and the greatest of all time (GOAT).

Smith said he realized the GOAT is where he really wants to be in life, pushing physically and mentally.

“I’ve been doing great,” he said.

Lampron is teaching her students how to play the game of life, how to navigate in the real world.

“They need the opportunity,” she said, “to get angry, calm down, be self-resilient, be self-reliant, and most importantly ask for help.”

Her number one skill for graduates is to know how you find the helpers. To be successful in life, she believes, they will need to be able to find the helpers at college, in a job, and in their relationships.

As Lampron and I were talking, her phone is lighting up with texts. All of her students — all 807 — have her cell phone number. They are letting her know why they are late or why they won’t be in school because it is her expectation that they will let her know.

“This is how you do the work,” she said.

To do what she believes is in the best interests of her kids, Lampron at different points in time has had to be willing to take on parents and teachers and counselors and central office.

She had to broker a truce with leaders in the community, including leaders of gangs.

The SRO told me she has been able to get buy-in because people can see L Money loves her kids.

She is brave above all for her students. And that is not in the job description of principal.

“Dr. Lampron is the real deal. She embodies the transformational leadership needed to lead a school today, balanced with a level of curiosity, empathy, dedication, and work that kids deserve. She is truly all in for students, and I am not surprised at the broad impact, inspiration and impact she brings to her role.”

— Dr. Monique Perry-Graves, Executive Director, Teach for America North Carolina

Editor’s note: Shout out to Haley Owens, principal in residence at SWEHS, who planned our visit. Thank you!

Shout out also to the Oak Foundation, who supports our work to understand learning differences, and is willing to learn alongside of us.