|

|

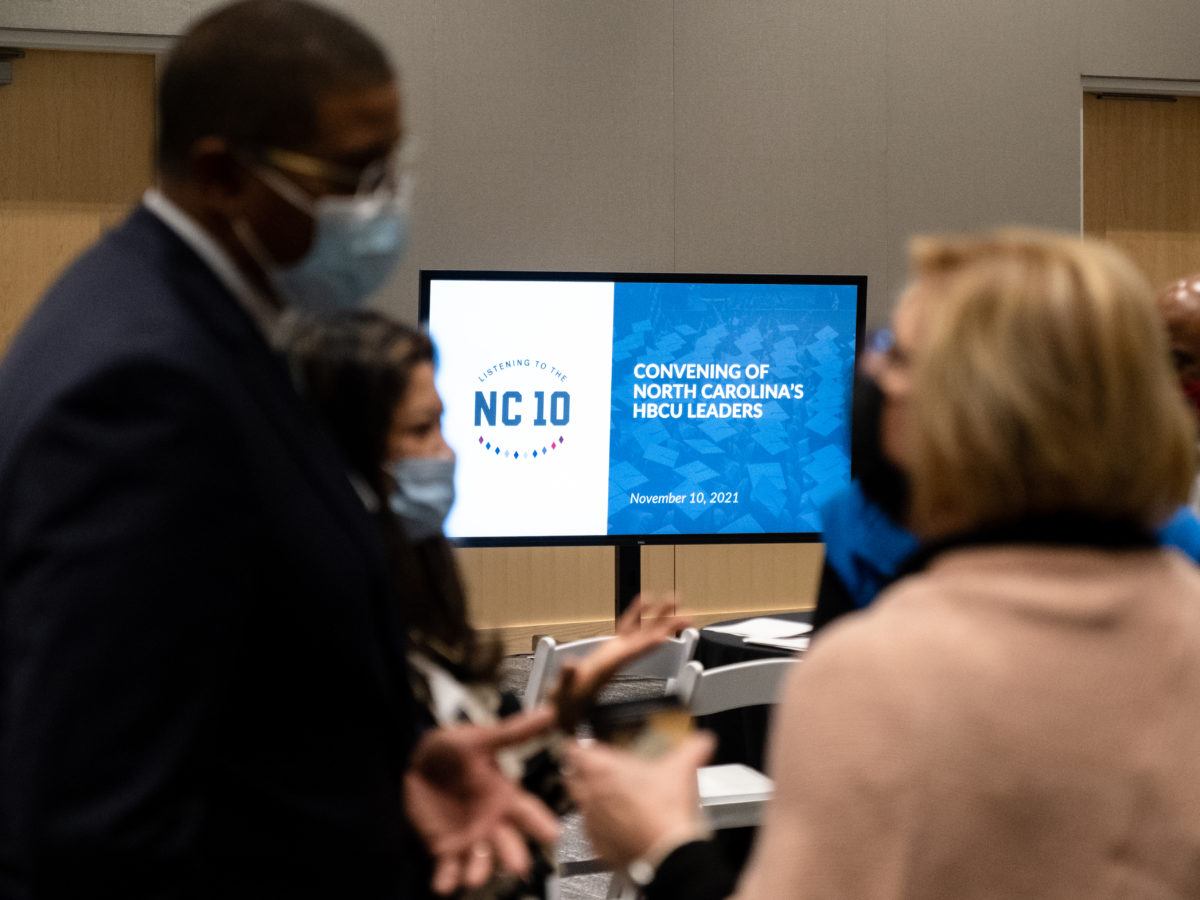

“We have never convened to do business,” said Minnie Forte-Brown on Aug. 31, at the first convening of North Carolina’s 10 historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) held at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte. Forte-Brown serves as senior advisor to the NC10 initiative.

The NC10 include:

- Shaw University in Raleigh (1865).

- St. Augustine’s University in Raleigh (1867).

- Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte (1867).

- Fayetteville State University (1867).

- Bennett College in Greensboro (1873).

- Livingstone College in Salisbury (1879).

- North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro (1891), the largest HBCU in the United States.

- Elizabeth City State University (1891).

- Winston-Salem State University (1892).

- North Carolina Central University in Durham (1910).

While the NC10 share a common heritage, the public and private institutions are small and large, rural and urban, independently established and land grant.

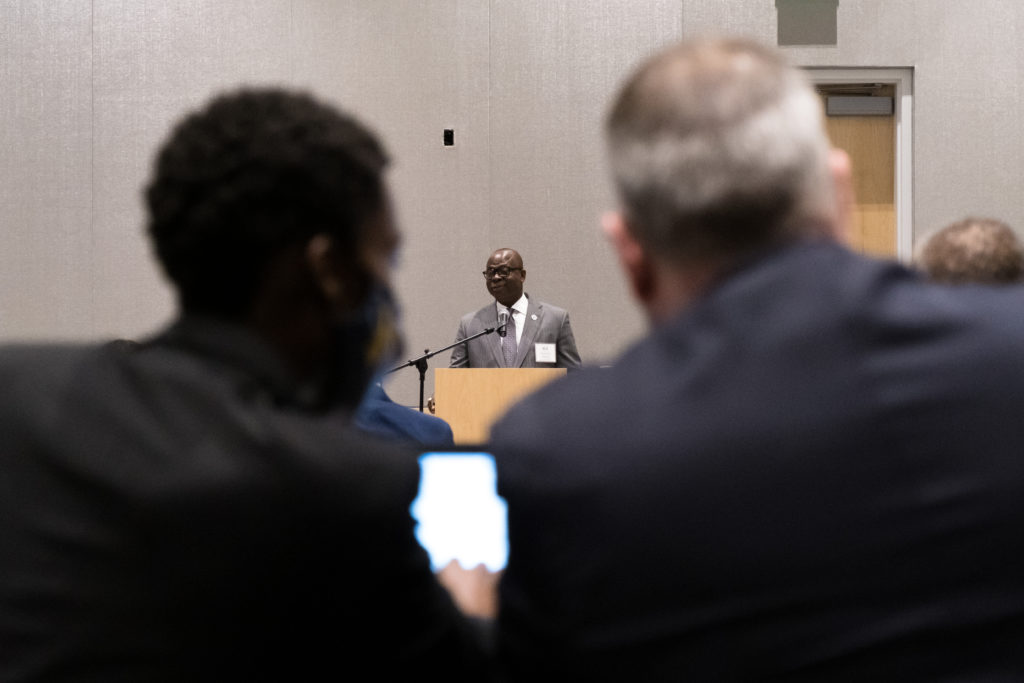

“Guess what I’ve been able to say in my recruiting of these companies?” asked Gov. Roy Cooper at the second convening of the NC10, held on Nov. 10, at N.C. Central University in Durham. “North Carolina has more four-year HBCUs than any other state.”

As North Carolina focuses on educational attainment, economic development, social mobility, and teacher diversity, the Center for Racial Equity in Education (CREED) envisioned an initiative to engage the HBCUs individually and collectively, listen to them, and assess the challenges and opportunities going forward.

The Hunt Institute, myFutureNC, and EducationNC also participated in the initial phase of the initiative.

The history of the NC10

The story of higher education in North Carolina cannot be accurately told without including its 10 HBCUs, yet they have received a fraction of the attention — and funding — compared to their predominantly white counterparts. The story of HBCUs in North Carolina is one of self determination and Black agency.

This report, “Fertile Ground: The Stories of North Carolina’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” documents the history of each of the 10 through present day.

“The colleges and universities that make up the NC10 are not institutions that just serve their students and alums.

They enrich their communities, providing deep histories, vital economic impacts, and bright futures.

Increased investment and attention to these schools will benefit the State of North Carolina and every one of its citizens.”

— Fertile Ground

Findings and recommendations from the campus visits

From April to August, the initiative conducted on-site campus visits to all 10 HBCUs.

Ten points of interest emerged from the visits: institutional assets, windows of opportunity, faculty and staff, governing structure, infrastructure, student population and experiences, evaluation and metrics, COVID-19, funding, and structural racism.

To improve educational attainment and increase the institutional prominence of HBCUs, the recommendations, issued by CREED, include the following:

- NC10 | Develop a shared agenda based on commonly held strengths and areas of need.

- NC10 | Formalize a collaborative network among all 10 institutions for mutual benefit.

- NC10 | Adopt best practices for increasing attainment.

- Policymakers | Replicate federal efforts to support HBCUs at the state level.

- Policymakers | Pass legislation that modernizes HBCU infrastructure and enacts restorative funding.

- Policymakers | Establish a North Carolina Office of HBCUs.

- Stakeholders | Tell the full stories of the North Carolina HBCUs.

- Stakeholders | Financially support a North Carolina HBCU.

- Stakeholders | Make the economic case for supporting North Carolina HBCUs.

- Philanthropists | Grant North Carolina HBCUs unrestricted gifts.

- Philanthropists | Form a philanthropic giving network focused on North Carolina HBCUs.

“It’s the totality of our HBCUs that contributes to a vibrant North Carolina and everybody has something different to contribute.

Each HBCU has a strength and distinction.”

— Listening to the NC10

Convening the NC10

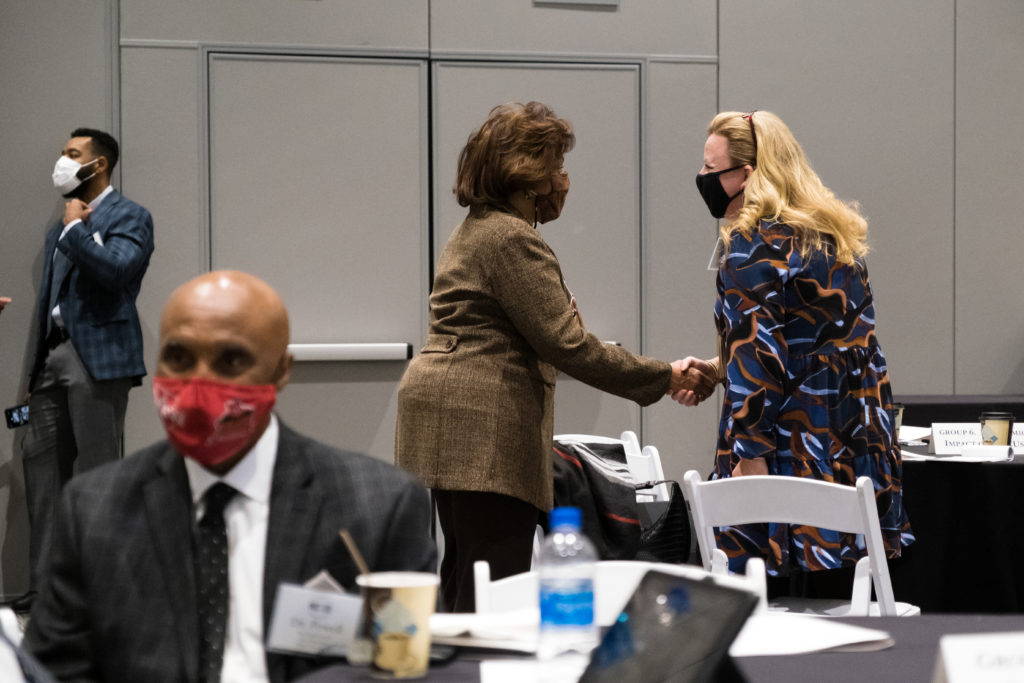

To date, two convenings of the NC10 have been held: the first in August and the second in November. Both included representatives from all 10 HBCUs.

At the first convening, the initiative previewed key findings from the NC10 listening tour and myFutureNC discussed the role of the HBCUs in reaching the state’s 2030 attainment goal.

Rep. Alma Adams, representing the 12th district of North Carolina in the U.S. House and co-chair of the bipartisan HBCU caucus, and Adam Harris, staff writer for The Atlantic and author of “The State Must Provide,” provided remarks about the past, present, and future of HBCUs.

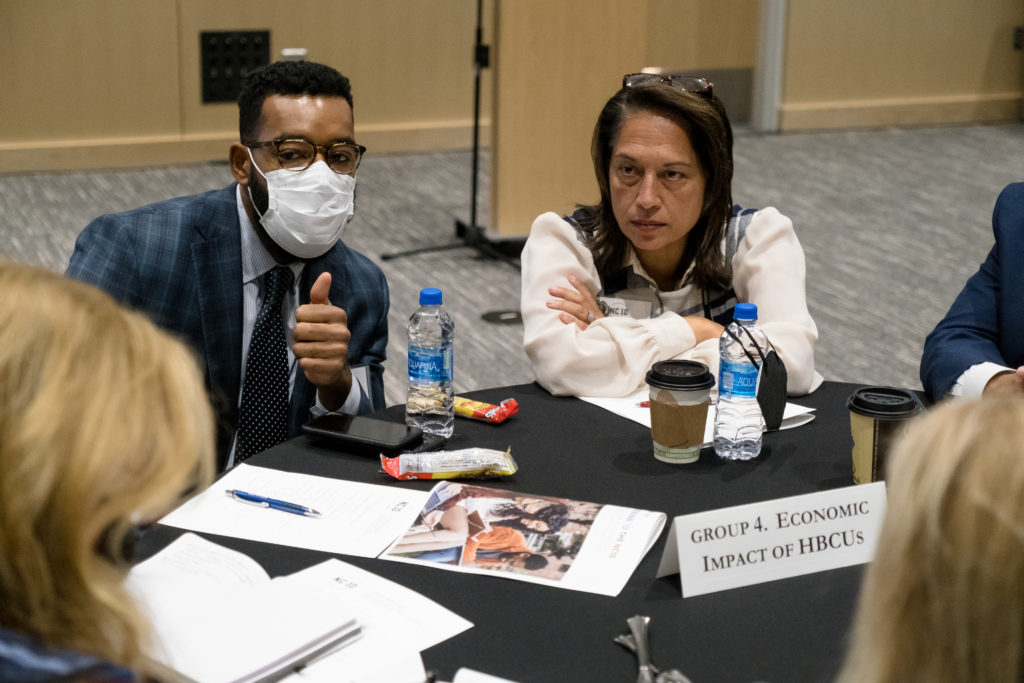

The second convening included philanthropists and policymakers with time spent in working groups.

“We are brainstorming, collaborating, and strategizing to effectively communicate the academic, communal, social, and economic impact of the public and private HBCUs in North Carolina,” said a tweet from the office of external affairs for N.C. A&T University.

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

Cornell Watson/EducationNC

This work is just beginning.

A federal and state policy scan by the Hunt Institute published Wednesday provides an overview on the history, successes, and challenges of the 10 HBCUs in North Carolina. In particular, the brief utilizes data and research to highlight the success of HBCUs in enrolling and graduating students who are often left at the margin, including low-income, transfer, and students of color, according to the Hunt Institute.

We look forward to continuing to listen and work in partnership with the NC10, identifying strategic opportunities to support HBCUs individually and collectively.

“We stand at a moment in time when we can take advantage of these opportunities,” said President Clay Armbrister at Johnson C. Smith University. “And a group like the NC10 can serve as a springboard to move items to an action.”

Editor’s Note: The John M Belk Endowment supports the work of EdNC and the NC 10.