You are hearing lots of stories about all the ways districts are trying to make the internet available to their students. But your questions to us make it clear that many of the stories are short on details about exactly how the districts are implementing various solutions. This is about how one district made Wi-Fi available in school parking lots — tech specs and all.

“No child left offline” might be the phrase I remember most when COVID-19 is over and done — a quick play on “no child left behind” by FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel.

As states try to figure out the state and federal policy changes and the dollars needed to make broadband accessible everywhere and get children online, schools and districts need a solution — and they need a solution now.

Students need devices, access to the internet, and enough training to be able to be in touch with a teacher, understand how to use the various learning platforms, and do the work.

Heath Belcher, the assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction of Lincoln County Schools, says districts are focused on access to the internet because it is “what is not changing.” Which devices to use, which funding streams will pay for them, the various learning platforms, how to train students, parents, and teachers — all of that is a lot more uncertain.

Access to the internet is a place to start.

Some districts are providing hot spots, which requires cell service. Some districts are deploying buses equipped with Wi-Fi, which requires a safe place to park the bus in near enough proximity to students. Because of how the county is populated and the topography, neither would work in Lincoln County.

Located to the northwest of Mecklenburg County, Lincoln County isn’t even considered rural, but for sure parts of it are, especially western Lincoln County. About 86,000 people call Lincoln County home, according to the Census Bureau, and about 11,400 of them are students in Lincoln County Schools.

The Census Bureau reports that 86.5% of households have a computer, and 79% have a broadband internet subscription. According to a recent survey by the school system, about 2,000 of the students responding said they had some kind of internet access issue.

It’s not just students that don’t have access to the internet. As I drove into the county and toward West Lincoln High School, I passed by Union Elementary. The parking lot was packed. When I asked what was going on, I learned that teachers are coming to school to access the internet.

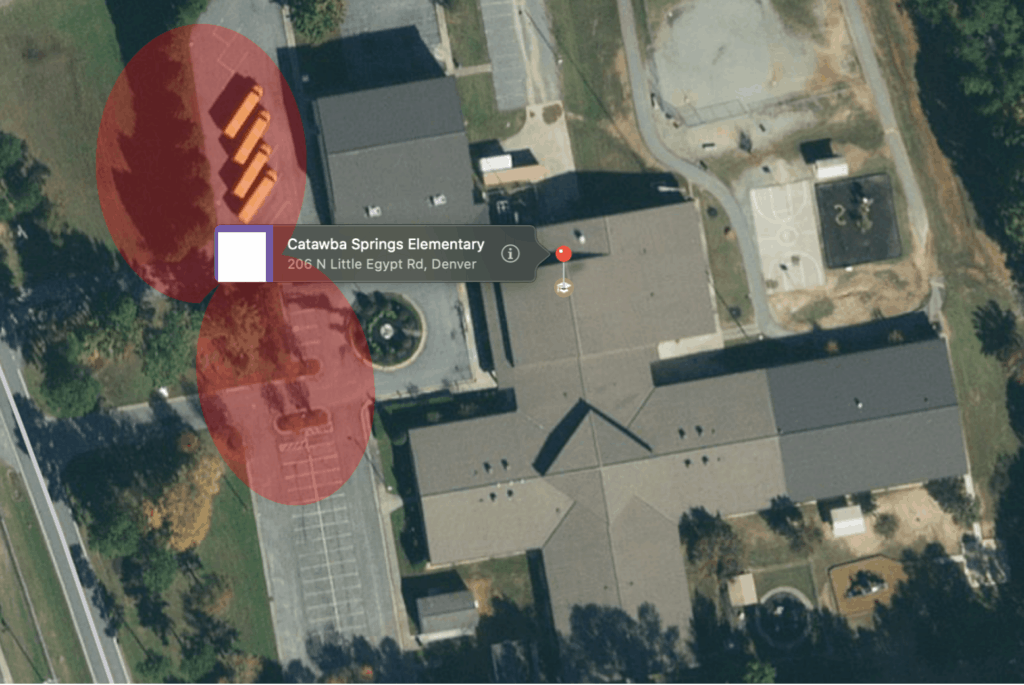

As the realities of COVID-19 set in, Lincoln County Schools decided to provide Wi-Fi in the parking lots of all 23 schools.

Fast. Like in just over two weeks. Bringing online two to three schools each day.

For each school, the district provides a map showing the exact location of Wi-Fi coverage. Here’s a link to all of the maps.

This step, says Belcher, began to address three essential questions. It addresses equity, removing at least some of the barriers to learning. It addresses student engagement, and in addition to access to remote learning, creates opportunities for students to be in relationship with teachers and other students. And it addresses what the district calls “expansion,” which means it also helps parents and the community.

The infrastructure needed right now — and for the future

Steven Hoyle is the director of technology for Lincoln County Schools. “There are a lot of districts trying to figure out how to provide some internet access to students,” he said.

“We call it infrastructure for a reason. It’s just like the highway. This is infrastructure we can build on for the future.”

— Steven Hoyle

Internet comes to the district via MCNC‘s statewide infrastructure. Then, Hoyle says, they distribute the internet from the hub of the network out across the county to all of the schools using fiber optic through a service contract with AT&T. Each school then operates its own wired and wireless networks.

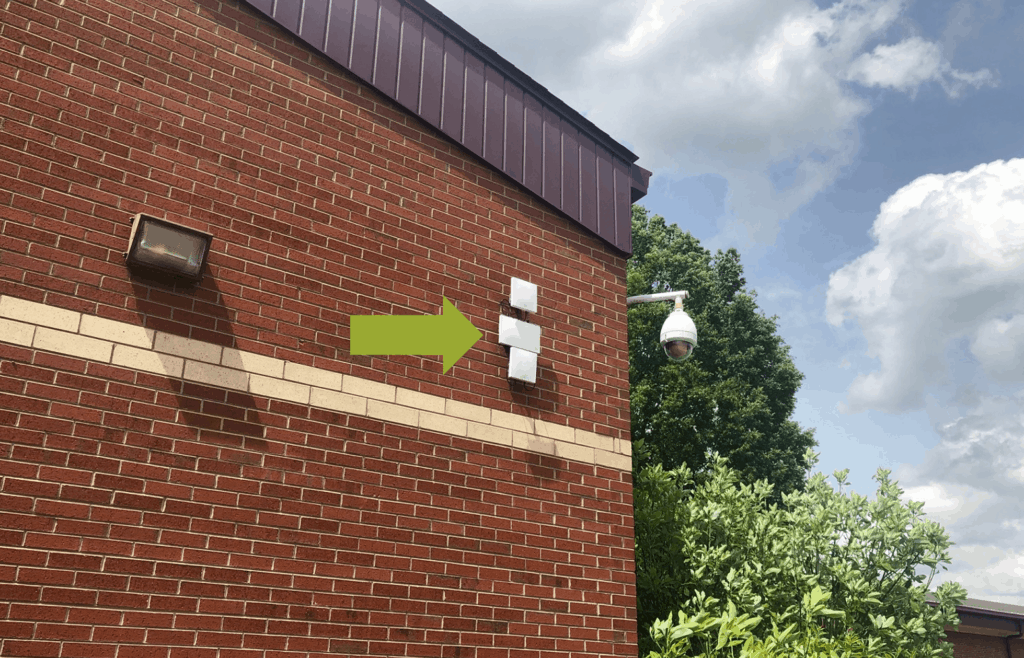

The school district purchased a wireless access point and mounted it on the exterior of a building at each school. Each wireless access point has special antennas designed for wide coverage.

Lincoln County Schools is using Cisco Meraki MR 84 wireless access points. I found one online for $1,624.99. Depending on the seller, the license type, and the antenna(s), the price ranges from $1,500-$2,300.

These types of access points are known for being good in tough, high-density environments (think sports stadiums). You can custom modify the antennas for each site.

Lincoln County Schools contracted with a local partner to put in the necessary cable and physically install the access points on the buildings. Each installation cost $350-$450.

The school system’s tech team then configured the access points, determining frequencies, congestion settings, and ensuring compliance with FCC guidelines (for instance, it has to be set to not interfere with the neighbor’s Wi-Fi).

Hoyle was very intentional about picking where to install the wireless access points. At West Lincoln High School, for example, it is on the outside of the gym for four reasons: public access in the parking lot, public access during athletic events, access for the buses, and because this area needs more surveillance.

Lincoln County Schools parking lot Wi-Fi is available from 6 a.m. – 9 p.m., seven days a week.

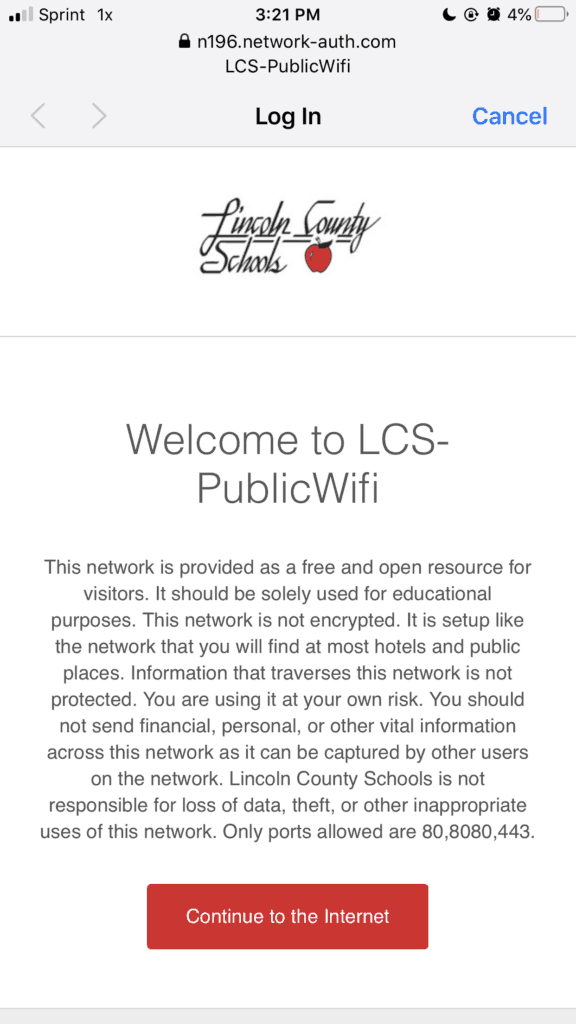

It’s an open network — just like you’d find at a hotel or Starbucks — and you have to check one of those acceptable use forms to get access to the internet.

Hoyle says, it’s “filtered internet,” which just means it’s filtering content deemed dangerous for students. He says they isolate the internet traffic from the school’s network so that it can’t be used as an access point for hackers. He says his team can see how people are using the Wi-Fi, throttling access to certain sites if needed (like sites with video).

He says each access point roughly serves 50-60 devices for general web surfing. It’s a finite resource, Hoyle notes. “The more you add to it, the slower it gets.”

The district used federal E-rate reimbursement funds to cover the costs.

Infrastructure is part of the ‘digital literacy journey’

The school district is not 1:1, meaning they don’t have a device for every child, even when they are in school.

Lory Morrow, the superintendent, calls the work to increase the digital footprint a “digital literacy journey with the community.”

Hoyle says COVID-19 makes it clear that we need to have a conversation as a state about whether devices and tech infrastructure should continue to be treated as capital expenses funded by local counties or whether its time for the state to acknowledge that access to a device, internet, and training for each student is an operational expense in providing a sound, basic education.