On a cold, gray day in November of 2013, I walked with my younger brother down a quaint street in Wilmington, Delaware. Regarding all things tech, my brother is the nerd of nerds, and on this day he was describing all of the ways he could think of to incorporate 3D printing into my classroom.

In that moment I kind of brushed him off, but something he said stuck with me. He mentioned that he had heard about MakerBot working with DonorsChoose.org to get 3D printers into classrooms. I generally seek the leading edge of things being tried in the classroom, so I was intrigued, but in that moment I had little capacity to act on the idea.

Several months after our chat, the idea of bringing 3D printing to my school was still rolling around in my brainpan, so I decided to check it out. By my calculations I had nothing to lose by putting up a DonorsChoose.org campaign. If successful, I’d have a shiny, new printer headed to my classroom. If unsuccessful, I would have raised money for some other teachers.

On March 28, 2014, I created Making the Body, my first DonorsChoose.org project. The project’s stated fundraising goal was $2,637. Once launched, the first $1,000 came in easily, and it was mostly contributed by family and friends. As the first wave of donations slowed to a trickle, I made a push to my professional network that netted another $800 or so. Then I was stuck, really, I had no idea where the last $800 was going to come from.

So the campaign sat, lonely and untouched, for close to two months. With three weeks left in our allotted fundraising period, I had all but given up hope for scratching together the remaining funds. Then I got a notification. Two-hundred dollars had just been contributed by a person that I did not know, then another $25, and another $50. Donations started rolling in from across the country; given by people I didn’t know, but that had been compelled to pitch in. The remaining balance for my project came in over the course of a couple days right as our timeline was drawing to a close.

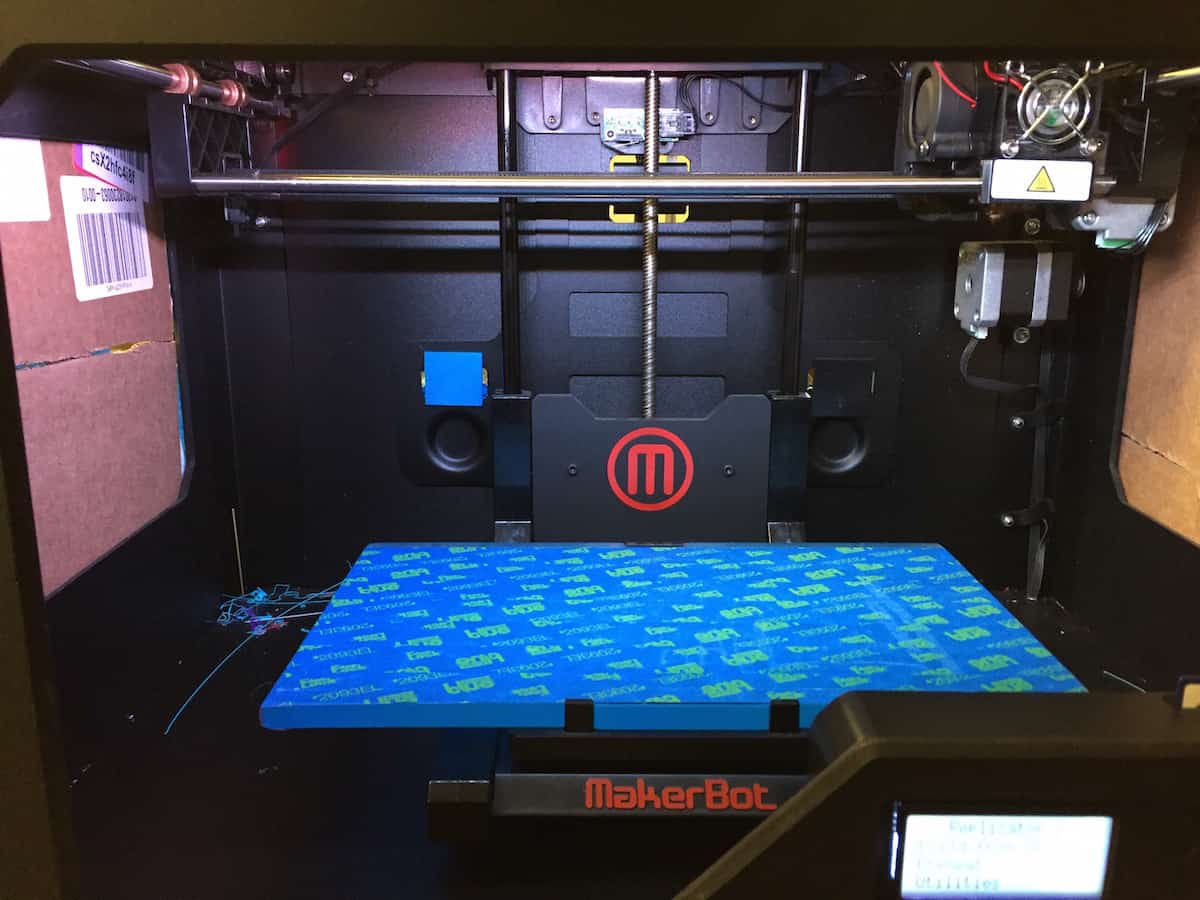

In August 2014, a giant box bearing my name arrived at the school.

I’d seen a couple of projects done in other classes, but I wasn’t particularly compelled by any of them. In my search for inspiration I ran across e-NABLING the Future, an organization that links 3D designers with people that have 3D printers in an effort to provide prosthetic hands for children in need.

I thought, “My students 3D printing and building prosthetic hands for kids who are missing some or all of their fingers? Win!” Never mind the fact that I had never used a 3D printer, my students had never heard of a 3D printer, and we would be responsible for producing actual prosthetics hands for kids with real needs. What could go wrong?

I reached out to e-NABLING the Future and within a couple of weeks they had matched my class with three children: one in Ohio, one in California, and one in North Carolina. On the first day of the project I gave each of the teams a file introducing them to the kid that they would be building a hand for.

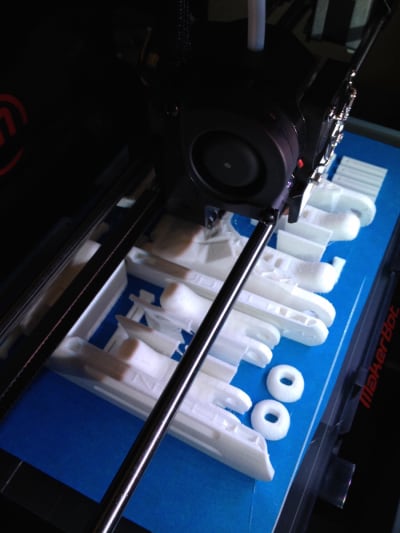

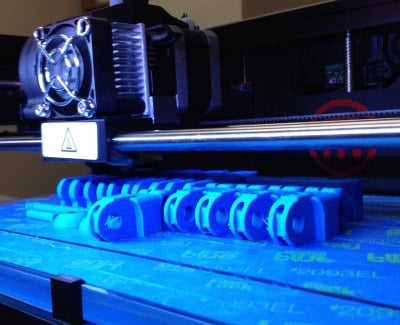

Immediately they were hooked, leaping head first into crafting carefully worded emails to families, learning how to use 3D printing software, and wrestling with the quirks of our printer.

I’d love to say that all went smoothly, but there were many lessons in perseverance and problem solving along the way. Through the project my students felt the crushing disappointment of walking in to find that the printer had inexplicably stopped after completing 19 hours of a 20-hour build; together we contacted families to explain that delivery of their hand would be delayed because our printer had broken; and I learned to let students feel the weight of the responsibility that comes through projects that actually impact the lives of other people.

After two months, five news reporter visits, and countless media articles, we finally shipped four prosthetic hands off to their eager recipients.The fifth hand had been built for a boy that lived just a few miles down the road. He and his family had the opportunity to visit the class to see his hand in process, and they were able to come to the school to take personal delivery of the finished product.

On that day, I watched with swelling pride as two senior girls presented a young boy with a prosthetic hand that would change his life. In that moment there were few dry eyes in the room. One of the girls would tell me later, “Mr. Kite, when I am old and have forgotten everything, I hope I remember this project.”

I could wax poetic about the myriad lessons I learned from this project, but none are more important than this: make learning real for your students. The admonition to help students connect their learning to their world has become trite, but that doesn’t make it untrue.

By saddling students with the responsibility of producing a product that had a concrete impact on the life of another person, I removed their escape hatch. The students were well aware that their failure to complete the project would mean that a child would not receive a hand. Obviously, it is impossible to make every classroom project this consequential, but the lesson is universally applicable.

Students who understand that the product they are producing is to be seen and interacted with by people beyond the walls of the classroom automatically work harder, produce better products, and more fully internalize the content.

Like most of you, I’d heard all of that before, but I didn’t really get it until I watched a young boy strap on a bright red hand.