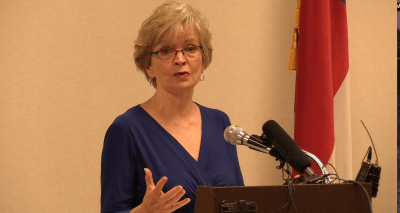

This past July, I was fortunate enough to travel to the countries of Singapore and Malaysia with 40 other North Carolina educators, as part of the Global Teachers program through The Center for International Understanding. It was the final chapter of my whirlwind term as North Carolina Teacher of the Year.

This was my first experience traveling abroad.

The vast majority of our time was spent in Singapore, immersing ourselves in the local culture and learning about their approach to education. Singapore touts one of the world’s highest ranking education systems and has become the prototype for so many other nations. Much is made about Singapore Math (the countries patented method for math instruction), and the country also excels in cognitive skill development, problem-solving skills, and the ability to think flexibly and creatively. Its students regularly perform at or near the top of the worldwide rankings on PISA, a respected international test of student knowledge in reading, math, and science (the U.S. typically doesn’t fare nearly as well).

While no nation gets it completely right, there is much to be learned from this tiny little Asian country off the southern tip of Malaysia. Its evolution from a small fishing village to a developed country with a thriving economy in less than 50 years was no accident. Rather it was the result of very careful planning and execution by the government, chiefly by the nation’s late visionary leader Prime Ministry Lee Kuan Yew.

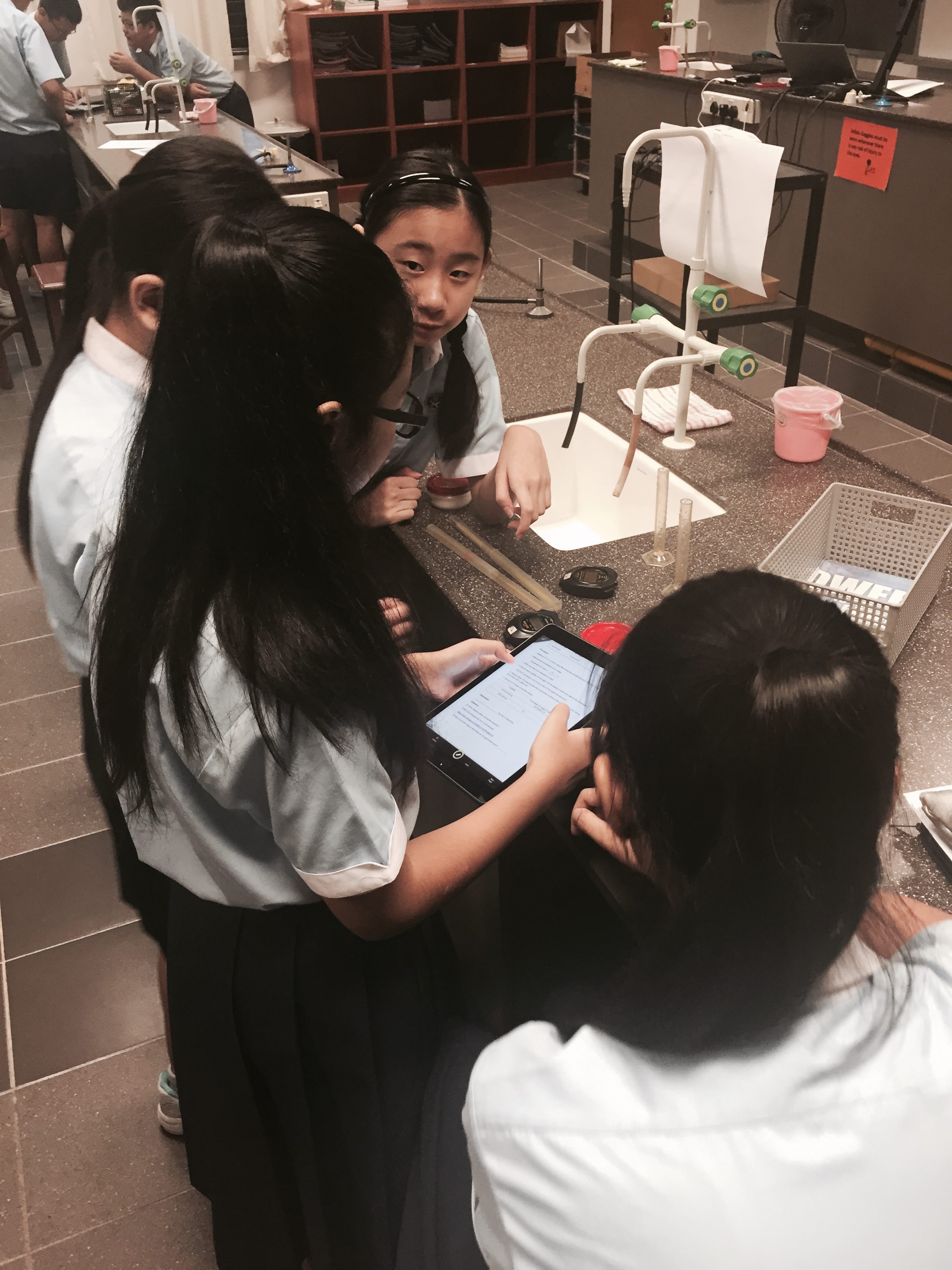

I spent the majority of my time in and out of classrooms at the various Future Schools – those recognized as “peaks of excellence” – meeting with faculty members, speaking with students, and getting tours of the facility.

As we entered the classrooms to observe instruction, students would greet us in unison by standing and saying, “Good morning teachers.”

It was a level of respect and admiration I had never felt before.

It was a cultural expectation to do so, but it still felt good. Teaching is a well-respected profession. Enrollment in teacher prep programs is highly competitive and candidates are intensely vetted. They are in charge of shaping the future after all and the level of expectation and support is felt. As a result, the position holds prestige and the pay is “not something people ever complain about.”

For any roles that a teacher would like to occupy beyond the classroom there is training and professional development offered by local universities which is subsidized by the Ministry of Education (MoE). Something as simple as becoming department chair may require training and that would be something sponsored by the school. You cannot even become an administrator unless you have successfully taught and been recruited for your talents – a stunning contrast to the way school leadership is conducted in the States.

Perhaps most pronounced was the overwhelming sense of consensus throughout the country on this very point –

education is essential for the nation’s prosperity.

It seemed that everyone, from the cab driver to a member of Parliament, was in agreement and in no need of persuasion. An educated populace prepared to meet the needs of the 21st century is the greatest natural resource the country can produce. This sentiment permeated the environment and was felt wherever we went. It was a source of pride for commoners and a point of emphasis for policymakers. If the economy needs engineers and other highly skilled workers, then the axis of education should shift accordingly. This is the mentality.

In these schools, I bore witness to some of the most progressive and innovative approaches to engaging students. From partnerships with technology companies to develop applications for the classroom, to systemwide initiatives to form clubs that get students to become passionate about STEM. My eyes were wide open to the possibilities. We met with the MoE and listened as they presented on the evolution of education in the still very young nation as well as talked about their progress toward goals.

Singapore has an education system with several pathways for students to either enter the university or the workforce. It is what is commonly viewed as a tracking system based on abilities and ambitions, beginning with primary school then typically offering some sort of trajectory with several ladders and bridges in between. All schools are not Future Schools. Most are referred to as “heartland” schools, which are more reflective of the general population. However, even here, there is an expectation of achievement and investment in learning.

At one point while visiting the Infocomm Development Authority (IDA) – an entity of the government dedicated to supporting telecommunications and information technology development – the presenter paused while displaying all the various tools utilized by the schools. “All these technologies come from the U.S.,” he said. “These are all American companies, so I don’t know why you’re here.” This got a chuckle out of many in the North Carolina delegation, but the message was clear.

We have the capacity in our very own country to do more, we just aren’t capitalizing on it.

What is abundantly clear is the country has a collective mission and a sense of shared prosperity. There’s an overwhelming sense that they’re going somewhere, a destination meticulously mapped 50 years ahead, and education is the driving force. Whatever their fate as a nation, it will be the byproduct of how well they prepare their workforce. There seems to be a clear understanding in the education sector of that for which the students are being prepared. This is not an aimless pursuit, but one with a very efficient target in mind when developing curriculum. Whatever the needs of the society, the education is designed to meet it.

I suppose it would be a false equivalency to compare the United States to Singapore. After all, we are much older, larger, and have a vastly different national history. Still, I took many lessons from Singapore. As a member of the MoE put it, “We are a small nation. So our mentality is to stay on the cutting edge or we may not exist.” This thought process differs greatly from that of the world’s only remaining superpower. It often appears as if we’ve become complacent in our position as a “first-class” nation. We operate like this status has been cemented for perpetuity. By contrast, Singapore is leading in so many ways because their survival necessitates it. Failure is not an option.

If this framework doesn’t fit so neatly over our nation, how about our state? What if we in North Carolina adopted the same philosophy as Singapore.

Would we continue to hover near the bottom in teacher salary and per pupil expenditure?

Would our enrollment in teacher prep programs be so rapidly decreasing?

Would our overall rate of educational spending continue to trend downward as our population grows?

To honestly answer “yes,” we must recognize the same profound truth that Singapore has, that our collective prosperity is dependent on our ability to provide a quality education to all. After witnessing such a powerful example, I worry that we may not be ready for this. Perhaps our own survival necessitates bold leadership that looks generations ahead and refuses to accept anything but the best as an option.

Comparing the Republic of Singapore to North Carolina:

Singapore has 227 square miles. North Carolina has 53,819 square miles.

The population of Singapore is 5.5 million. The population of North Carolina is 9.9 million.

The gross domestic product of Singapore is $452.6 billion. The GDP of North Carolina is $491.5 billion.