Judge David Lee, who is presiding over the Leandro case, has been invited to testify in front of the Senate Education Committee during the short session. The invitation asks him “to share your perspective and recommendations on education policy.”

In the aftermath of the WestEd report detailing how the state can meet the mandates of the long-running case, there has been some discussion about who exactly was consulted in the making of the report.

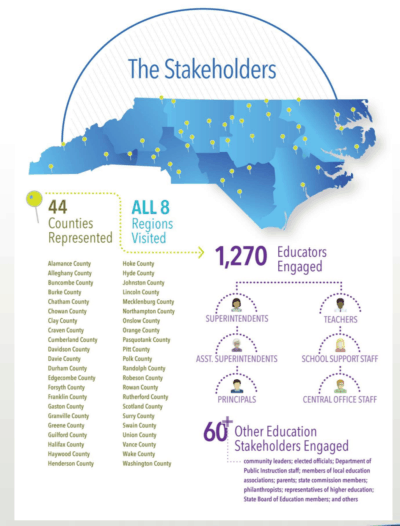

A wide range of stakeholders — 1,270 educators and 60+ other education stakeholders, according to a presentation from WestEd — got a chance to weigh in. But there is more confusion about what role the General Assembly played.

Susan Mundry, director of learning innovations at WestEd, named Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, chair of both the K-12 and K-12 appropriations committees, as a key person that was consulted by WestEd. But Horn takes issue with that.

“I have not had any ‘discussion’ of WestEd. Very early on, I had dinner with a couple of folks and we talked about WestEd possibly doing a report … but nothing specific,” he said. “I am interested, but nobody has really talked to me about it.”

In an email, Horn said that his discussion with WestEd was more an informal discussion. But he didn’t really consider that a “consultation.”

In an email, Mundry said that Horn met with her and her colleagues in June 2018 in his office. They met so she could “brief him on our work for the Court and inquire about relevant pending legislation and the committee he was leading to look at school finance.” She said that a WestEd staffer also had a short phone conversation with Horn, and that Glenn Kleiman of the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation had some “informal check ins” with Horn before the final report was submitted.

Horn said he doesn’t remember all those meetings.

“I am the first to admit that I do not remember many of the meetings that I have, but I have a LOT of meetings. I would think that I would recall this one. Yes, I did have an informal meeting with Glenn Kleiman (and I do mean informal). But I do not recall the meeting in my office or the phone call. But June of 2018 was a very long time ago! Besides, I probably thought the meeting was all about the Jt. Task Force on School Finance and did not connect the dots back then,” Horn said in an email.

Why is this important? State Board of Education Vice Chair Alan Duncan summed it up best at the most recent meeting of the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education.

“Judge Lee (the Leandro judge) made a number of comments about legislators being involved in this process and he asked actually questions of WestEd about how much time had been spent with the legislature as part of their work,” Duncan said. “There were some conferences but they were fairly limited to this point, and it’s an important point for Judge Lee I think that the legislature become involved in the process now that this work has been done.”

Speaking of the Governor’s Commission, it doesn’t include any lawmakers either.

Back to the WestEd report. Mundry said in an email that other than Horn, no other members of the legislature were consulted, though proposed education legislation in the legislature was tracked.

And Horn is on his way out of the General Assembly. He is running for state Superintendent of Public Instruction, and win or lose, he will be vacating his seat in the legislature. Even assuming he was consulted by WestEd, his absence means the one point of contact between the court and the General Assembly will soon be gone.

As Judge David Lee awaits a report from the Leandro parties laying out the plan to meet short-term goals related to Leandro, it’s clear that any solution that leaves out the General Assembly isn’t going to work for the court.

So, the question has been hanging out there: What’s done is done, but who is going to reach out to lawmakers now?

And then yesterday, Senator Deanna Ballard, R-Watauga, sent a letter to Judge Lee inviting him to come talk to the Senate Education Committee during the short session.

“For decades legislators have grappled with issues and policy options on how to best meet the challenge of providing the opportunity for a sound basic education for all of North Carolina’s children,” she wrote. “The good news is that everyone wants our children to get a quality education that’s delivered effectively and efficiently. Opinions differ as to which education policies are most effective and best for our diverse student population. I want to hear and be in a position to consider as many of those opinions as possible, because that’s what fosters better policy outcomes.”

She goes on to note that the Leandro case has been ongoing for a “quarter-century” under six governors, 13 legislatures, and under state control by both Republicans and Democrats. She says this “points to two key realities:”

“1) There are no easy answers to questions of which education policies deliver the best outcomes, and 2) a courtroom is not the optimal venue in which to resolve complex policy challenges that have existed since the very first authorization of spending public funds for K-12 education more than 150 years ago.”

Recommended reading