According to the consent order signed by Judge David Lee, a plan of action for the provision of the constitutional Leandro rights must ensure a system of education that includes:

“a system of teacher development and recruitment that ensures each classroom is staffed with a high-quality teacher who is supported with early and ongoing professional learning and provided competitive pay”

and “a system of principal development and recruitment that ensures each school is led by a high-quality principal who is supported with early and ongoing professional learning and provided competitive pay.”

This is the first piece in a week-long series that will examine each of the components of the Leandro consent order through the lens of schools and communities in North Carolina. Follow along with the entire series here.

Clayton High School is a big school, and it’s getting bigger. When Principal Bennett Jones started at the school in 2016, it was just over 1,600 students. Now, it’s swelled to 2,000, and they’re all packed in a school that’s more than 100 years old.

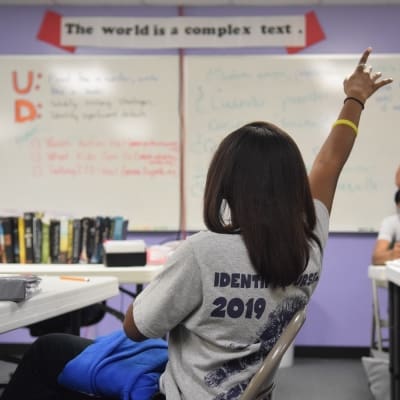

The school tries to cater to all its students: white, black, Latinx — some whose parents and grandparents went to the same school, and some who just moved to the country. It’s got advanced placement classes, career and college promise, career technical education, and even life-skills classrooms. But more and more what Jones was noticing was that the traditional school setting and the traditional school day wasn’t for everybody.

“What I’ve tried to do … is help to move from the traditional scope of school to what is the 21st century vision of school,” he said.

In keeping with that philosophy, two years ago, he launched something called the Comet Academy. The Clayton High School students are known as the Clayton Comets, but the academy was for those students with very specific needs.

It was essentially an afternoon school that ran from 2:30 to 6:30. If students had other things they had to do in the course of the ordinary school day, they could come and get their education done during the later afternoon block and eschew the traditional schedule. The school within a school was a success — but there was a hiccup.

“This year, funding got cut for that, so we couldn’t provide transportation,” Jones said. “So we were left with a gaping hole.”

This is a problem for a number of students, many of whom work and are even major income providers for their family. Not to mention the students who don’t adjust well to a traditional school setting either behaviorally, socially, or academically.

So this year, Clayton High came up with C2PLUS (Comets Plus). It stands for Commitment to Personalized Learning, Understanding & Success.

It cuts up the school day into two blocks, one from 7:15 in the morning to 10:30, and one from 10:45 in the morning until 2:00 in the afternoon. Since it’s within the normal school day, Jones was able to get by without having to pay extra teachers. Students can come in and work in small group settings while also getting instruction on social and emotional learning.

“This is a design for when students are not being successful in the traditional day,” Jones said. “If it’s not working in the traditional day, then why are we continuing to just fail kids?”

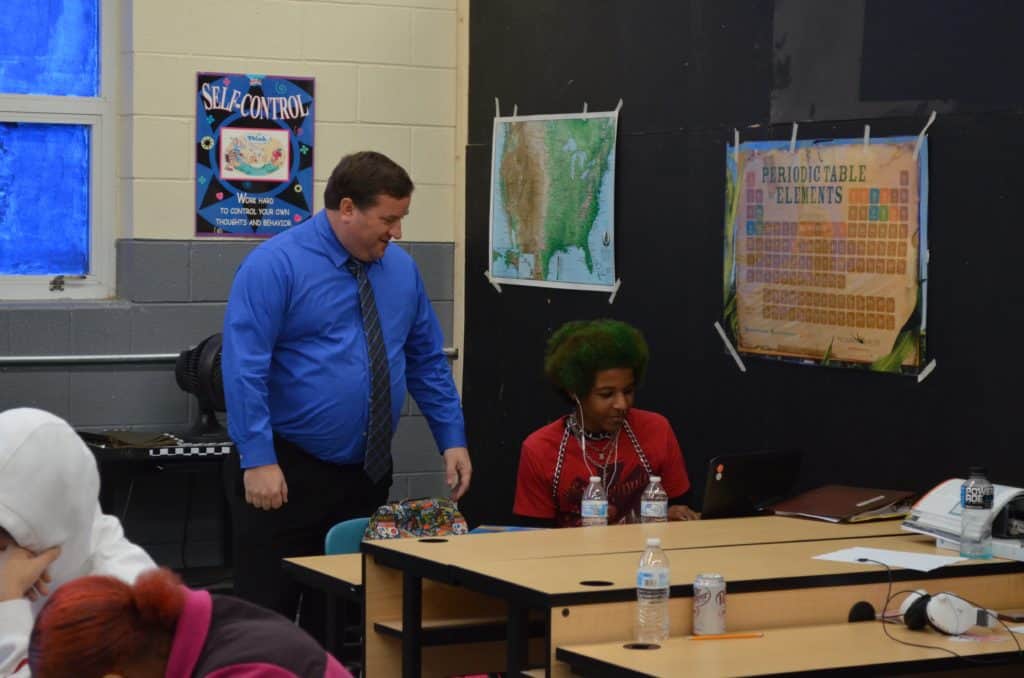

Students can work one on one with teachers. To get instruction in subjects the teacher isn’t familiar with, content experts use a multitude of strategies, including recording their lessons, FaceTime, and even Google Chats.

Jones explained that it forced teachers to rethink how they teach. Their instruction becomes more akin to tutoring, but it also gives Jones the opportunity to put effective teachers in front of more students.

“How can we take that effective teacher and put that student working with that effective teacher even if they’re not in the classroom?” Jones asked. “To me, it maximizes our effective teachers. It maximizes their impact across more students who would traditionally sit in their classroom.”

The students who come for the morning session eat lunch at the end and then can either ride the bus home or go to work. The bus then brings in the students for the afternoon session.

Right now, the program is done only by referral, but Jones hopes that one day it will become a choice for any student who thinks it better fits his or her needs.

Jones said that Comets Plus is an extension of something the school has been doing for longer: Comet Time. It’s a block of time during the day where students can sign up to be involved in clubs or other extracurricular activities, but they can also get remediation and support. This is another way Jones said he is able to put effective teachers in front of more students.

“When you talk about highly-qualified teachers, at the high school level it’s really been a mind shift for a lot of high school teachers to move away from teaching content to teaching kids,” he said. “That’s really what I think Leandro’s talking about when you’re talking about teachers that are high-quality teachers. You want high-quality teachers who are effective at disseminating information to where students can understand it.”

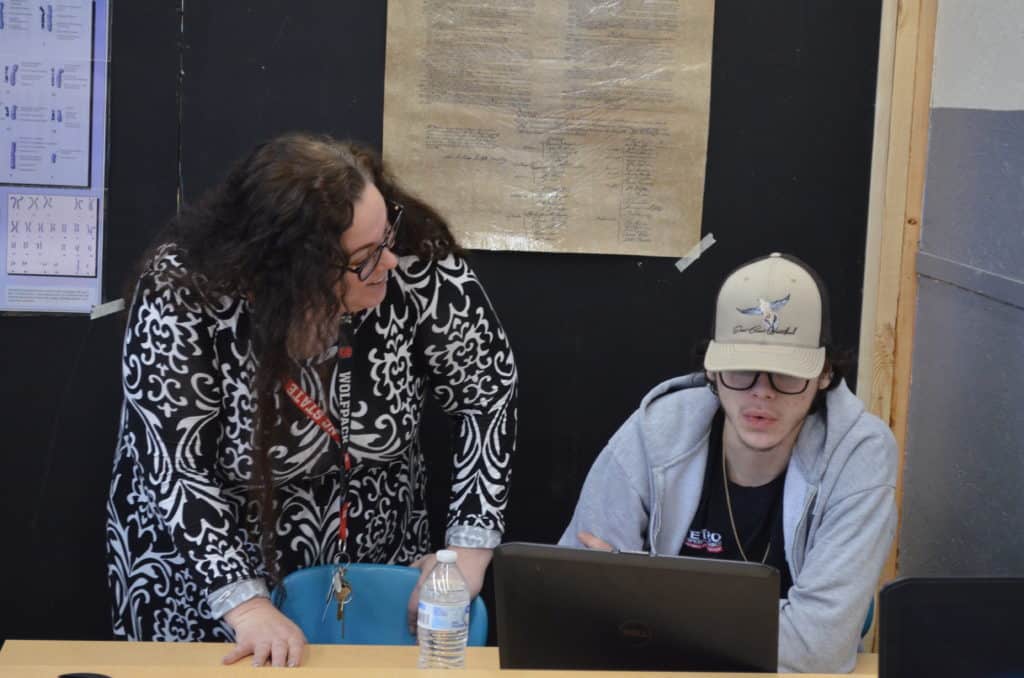

Jennifer Crisco is a science teacher at Clayton High School and a principal fellow at North Carolina State University.

She runs the morning session of Comets Plus. She explained that students come in and she works with them to look at their credit hours, come up with daily goals, figure out what classes or credits they need, and go about actually getting them.

She pointed out a packet from one student who was getting ready to drop out with only four credits as a junior. Since he’s been in Comets Plus, he’s already knocked out two more credits with credit recovery. Another student, a sophomore, had severe anxiety, and Comets Plus ended up being the ideal program for her.

“We find out what’s going to work best for them, and that’s how we teach them,” she said.

A critical need in Leandro

Clayton High School is an example of what can be done when high-quality teachers and principals work together to make sure students get what they need to succeed.

Teachers and principals are a focus of a recent consent order from the court hearing the long-running Leandro case. In the order, Judge David Lee lays out the seven things the state needs to implement, and the first two pertain to getting high-quality teachers and principals into schools.

“Identifying and retaining our best teachers in North Carolina is a central question for our schools and should be one of our state’s highest priorities. Teachers are the most important in-school factor on students’ academic success,” said John R. Belk, board chair of The Belk Foundation, during a discussion on teacher recruitment and retainment this month. “Our most talented teachers in North Carolina are the difference makers who can connect with students and contribute to their academic achievement.”

Again and again, education leaders say that the greatest indicator of student success is the presence of a high-quality teacher. The second is a high-quality principal.

But according to WestEd, the independent organization tasked with examining how North Carolina could meet the mandates of Leandro, North Carolina has a shortage of both.

Teachers

“North Carolina has gone from having a very highly qualified teaching force, as recently as a decade ago, to having one that is extremely uneven in terms of the numbers of candidates; the quality of teacher preparation, particularly for teaching in high-poverty schools; the extent to which the teachers have met standards before they enter teaching; and teachers’ growth and development once they enter the classroom,” the report states.

North Carolina has and is trying a number of tactics to meet the growing need. One is through the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program.

This is a program that had been around North Carolina since 1986. It offers scholarships to college for top-notch high school graduates willing to spend four years teaching in North Carolina schools. But in 2014, the General Assembly ended funding for the program.

It was brought back by lawmakers in a much more limited form in 2017. Advocates of the previous teaching fellows program have been calling for a greater expansion of the new program, as does the WestEd report.

Teacher pay is also an issue when it comes to teacher recruitment and retention. The Republican-led General Assembly has been steadily giving raises to teachers, but critics argue that it still doesn’t meet what teachers should be making.

The final 2017 long session budget raised teacher salaries an average of 3.3% in the first year of the biennium and 9.6% over both years. Starting teachers got no pay raise under the proposal. The highest raises went to teachers with between 17 and 24 years of experience.

In the short session budget, the numbers for 2018 were tweaked and teachers ended up getting slightly more — a 6.5% increase in 2018 instead of the planned 6.3 percent. Legislators also included raises for veteran teachers — those with 25 or more years of experience — who went from $51,300 a year in the original two-year budget to $52,000 in the short session budget.

In the 2019 long session, a stalemate between Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper and Republican lawmakers ended with no pay raise for teachers. Cooper was holding out for a larger pay increase while Republicans said that Cooper’s vetoes meant that teachers were having to go without any pay increase at all.

As of March 2019, North Carolina ranked 29th in the nation for teacher pay according to the National Education Association, making it the second highest in the Southeast.

North Carolina has also experimented with trying to give teachers more pathways for growth beyond moving into administration. In 2016, the state launched the Advanced Teaching Roles initiative. It can provide teacher leaders with higher pay, gets them more professional development, and can give principals a way to have more leadership in a school.

The WestEd report calls for an expansion of the Advanced Teaching Roles Initiative.

“Recent research suggests that using advanced roles productively can increase instructional capacity within schools, thereby giving substantially more students access to effective teachers. In addition, principals benefit from a distributed leadership structure wherein they provide regular support to a team of teacher-leaders instead of an entire teaching staff,” the report states.

North Carolina is also trying to change the way it does teacher prep. Senate Bill 599, passed in the 2017-18 legislative session, opens up teacher prep programs to programs other than those from universities. It also created the Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission which is working from the ground up to establish the standards by which educator prep programs run.

Currently, the commission is working on an accountability system that will decide what factors educator preparation programs are graded on by the state. A particular point of contention is whether to include the diversity of students, with opponents saying that educator prep programs don’t have a lot of control over the diversity of the student populations at their schools and proponents saying that if the programs aren’t held to account for the diversity of their students, then their student populations won’t get more diverse.

Principals

“Statistically, school leadership is found to be the second most important school factor influencing student learning, after teacher effectiveness,” the WestEd report states. “Since effective principals are critical for recruiting and retaining excellent teachers and ensuring they have supportive working conditions and opportunities for professional growth, the importance of the principal to students’ success goes well beyond what is found in the statistical analyses.”

Meanwhile, North Carolina doesn’t have enough principals entering the education pipeline or enough experienced principals in its schools.

“There has been a significant reduction in the numbers of candidates entering principal preparation programs over the past decade; many schools are led by inexperienced principals with fewer than three years of experience; and the

current principal compensation structure may be a disincentive to becoming a principal, particularly for becoming a principal in a low-performing school,” the report states.

North Carolina has a number of methods of training principals. They can go the normal route, like getting a master’s of school administration (MSA), but North Carolina also has innovative programs that it uses to bolster the principal pipeline.

One of the most well-known is NELA — the Northeast Leadership Academy. The program is housed at North Carolina State University and subsidizes tuition for higher degrees for potential principals, sets them up with internships, and gets buy-in from district superintendents ahead of time about potential candidates going through the program. It is now called the North Carolina Education Leadership Academy (NELA).

NELA, along with two other principal prep programs — The Sandhills Leadership Academy and Triangle Piedmont Leadership Academy — were able to thrive thanks to the federal Race to the Top Program.

In 2011, Race to the Top began offering education grants around the country. NELA got funding for its second year through the program.

But when Race to the Top money began running out, neither Piedmont nor Sandhills could get funding to continue, so they shut their doors, leaving only NELA as the state’s standout principal prep program.

The principal prep outlook brightened some during the 2015 long session. Lawmakers created the Transforming Principal Preparation (TPP) grant program and assigned the North Carolina Alliance for School Leadership Development (NCASLD) with administering it. The General Assembly appropriated $1 million for principal preparation purposes in 2015. In 2016, the legislature gave an additional $3.5 million to the issue. That money is administered by the NCASLD, which is supposed to identify principal prep organizations in North Carolina that can create strong programs for training principals.

Another innovative method used for recruiting principals is the principals fellows program, which has been around since 1993. It provides scholarships to people seeking an MSA degree to become a school administrator in the state. They can pick from 11 MSA programs to attend, and all the programs are within the UNC System.

In 2019, Gov. Roy Cooper signed into law a bill that would merge the Transforming Principal Preparation Program with the Principal Fellows Program. The WestEd report recommends expanding both of these programs.

Principal pay is also a factor in keeping good principals in the classroom. After years of issues with an overly-complicated principal pay schedule, lawmakers finally revamped it in 2017, taking away years of experience and just using school size and school academic growth to determine compensation.

A big criticism of this new principal pay schedule is that it encourages principals to work at schools with high academic growth. Basically, a principal gets his or her base salary based on the size of his or her school. Then he or she gets a little more money if the school meets academic growth. And the principal gets even more if the school exceeds academic growth. Critics worry that this would discourage principals from working at low-performing schools, often the ones most in need of strong leadership but least likely to achieve stellar growth.

That budget gave principals an average 8.6% salary increase over two years and assistant principals a 13.4% average salary increase over the biennium. In the 2019 long session, principals got an average 6.2% increase in pay. The overall structure of the schedule remains the same. Lawmakers also added up to $30,000 in supplements per year for principals willing to teach in low-performing schools.

The WestEd report recommends revising the principal pay schedule to, among other things, “Reward school leaders for their school’s progress on broader indicators beyond student achievement on standardized assessments.”

On the ground

When all the pieces are put together right, you get principals like Jones and teachers like Crisco.

They aren’t thinking about principal prep and teacher pay and advanced teaching roles, so much as they’re thinking about the students.

“It’s very important to me that all students get a chance. That they get a chance to be successful, because you don’t know where they’re coming from,” Crisco said. “You don’t know their home life. You don’t know. But what you do know is that without a high school diploma, it’s going to be a lot harder for them.”

She credits Jones with getting Comets Plus off the ground. She said it takes a particular kind of principal to come up with ideas like that.

“Dr. Jones is always in it for the kids. And he’s thinking, thinking, thinking,” she said. “He’s constantly going. He’s a big idea guy.”

Jones said he has been inspired by the diversity of his school to think about the fact that not every student learns the same way, and that maybe not every student should be taught the same way.

“It really creates an opportunity for us to look at what we can do as adults to meet the needs of that diverse student population,” he said.

Jones has begun inching in the direction of personalized learning through Comets Plus, and there is more to come.

Leandro resources

Everything you need to know about the Leandro litigation by Ann McColl

Sound Basic Education for All: An Action Plan for North Carolina (WestEd Report)

Executive Summary of WestEd’s Report

WestEd’s supporting reports:

- Statewide assessment system

- Statewide accountability system

- Cost adequacy, distribution, and alignment of funding

- Supporting student learning by mitigating student hunger

- High-poverty schools: Assessing needs and opportunities

- School success factors

- Attracting, preparing, supporting, and retaining educational leaders

- Educator supply, demand, and quality

- Developing and supporting teachers

- Best practices to recruit and retain well-prepared teachers

- Retaining and extending the reach of excellent educators

- How teaching and learning conditions affect teacher retention and school performance

Supplement to the Investment Overview and Sequenced Action Plan in the WestEd Report

Judge David Lee’s consent order

Draft priorities from the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education