Tuesday’s meeting of the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education was supposed to be its last, but the group’s recommendations on how to ensure the state provides equal educational opportunity to every child are still in the revision process. The group has been meeting since November 2017 discussing nearly every aspect of the state’s education system and how to live up to the 25-year-old Leandro lawsuit’s obligation.

The Leandro case is what established the constitutional right to a sound, basic education in North Carolina and, later, determined the state does not provide it to every child. The court has also outlined the following requirements to meet that mandate:

- “A ‘competent, certified, well-trained teacher who is teaching the standard course of study’ in every classroom;

- A ‘well-trained competent principal with the leadership skills and ability to hire and retain competent, certified and well-trained teachers’ in every school; and

- The ‘resources necessary to support the effective instructional program’ in every school ‘so that the educational needs of all children, including at-risk children, to have an equal opportunity to obtain a sound basic education, can be met.’”

Drafts of the group’s recommendations were discussed in detail for the first time at its last meeting in May.

https://www.ednc.org/2019/05/15/leandro-commission-discusses-draft-of-recommendations-for-the-first-time/

The group is broken into working groups focused on finance, teachers, principals, early childhood/whole child, and assessment/accountability. Since its last meeting, each of these groups took the questions and discussion around their priorities from May’s meeting and tweaked their draft recommendations. On Tuesday, those tweaks were presented and discussed.

One more meeting, potentially via a phone call, will be scheduled to further discuss the group’s recommendations. When the report from outside consultant WestEd is released publicly later this summer, the group will meet again to discuss the report. Here are the main highlights from Tuesday’s discussion.

What to do about charter schools

Several members brought up charter schools — their funding, their impact on district schools, and the recommendations’ implications for their students and teachers. The conversation started with an addition to the finance working group’s draft recommendations that suggests “the state should modify the funding for charter schools so that funds for new charter schools and charter school enrollment increases are funded by a direct state appropriation rather than in reduction to student enrollment funding for districts.” See the full recommendation below.

“We’re trying to talk about charter schools because they are in statute, they are public schools,” said Jim Deal, commission member, attorney, and leader of the finance work group. “But our comment here was really directed toward not reducing what goes to the traditional public schools to pay for support for charter schools.”

Rick Glazier, commission member and executive director of the North Carolina Justice Center, said he worries that students who move back and forth between charter schools and district schools leave district schools with less per-pupil funding from the state but still having to provide services for those children. He said local district schools are hurt by the movement of students.

“That seems to me to be a crucial point for school finance officers across the state,” Glazier said.

Helen Ladd, a commission member and Duke University professor of public policy and economics, said a provision like the one above could force the legislature to grapple with the cost of charter schools, but she worries it will lead to one-off allotments for specific schools rather than adequately funding an entire system.

“On the other hand, they’re already explicit about the voucher schools and they’re doing that outside [the system] and that worries me because I’m a believer in a system of public education,” Ladd said.

She echoed Glazier’s concerns that district schools are hurt when students move from charter schools back to their neighborhood schools.

“… If funding for traditional public schools is based on a per-pupil basis, based on the number of pupils in the traditional public school system, as students go to the charter schools, there’s still going to be less funding total that the traditional public schools and that still creates a problem for them because they still have to provide facilities in case the charter school students come back. They can’t just reduce teachers. It’s a much more complicated issue here than what we’ve got here and I don’t know what to suggest at this point,” said Ladd.

Leslie Winner, commission member and former executive director of Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, said charter schools are already funded directly from the state. She said she is worried about the proportion of local funds that charter schools receive.

“It’s very complex and all that without any evidence that they actually are providing a better education for anybody,” Winner said. “Some of them do, and some of them don’t. And to be fair, some of them do an excellent job and some of them do a lousy job and a lot of them are just about the same as every other public school.”

Alan Duncan, commission member and State Board of Education vice chair, said he worries that the students that require the most support and resources to educate, like children with severe disabilities, will always be the responsibility of traditional public schools.

“The high-needs students will end up in the non-charter public schools and there is no recognition of the financial differences and we haven’t said that very well in here,” Duncan said.

Winner suggested a funding formula similar to the one traditional public schools use, which includes money tied to specific school and student characteristics.

“The charters get their money directly from from state. What happens to the school system is that when they count their students they have fewer students. But you could have the charter schools’ allotments based on the characteristics of their kids to the same extent that the district schools’ allotments are based on the characteristics of the kids,” said Winner. “So they get disadvantaged student funds if they have disadvantaged students. They don’t if they don’t. They get gifted money if they have gifted kids. They don’t if they don’t, etc. That would make it seem fairer…”

Commission chair Brad Wilson, former CEO of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, suggested the finance team revise its charter school recommendation and come back with new ideas.

“Just revisit and rethink a bit to see to what extent point number nine can be improved if at all or what additional point needs to be made and come back to us with some thoughtful analysis,” Wilson said. “We could talk about this the rest of the day.”

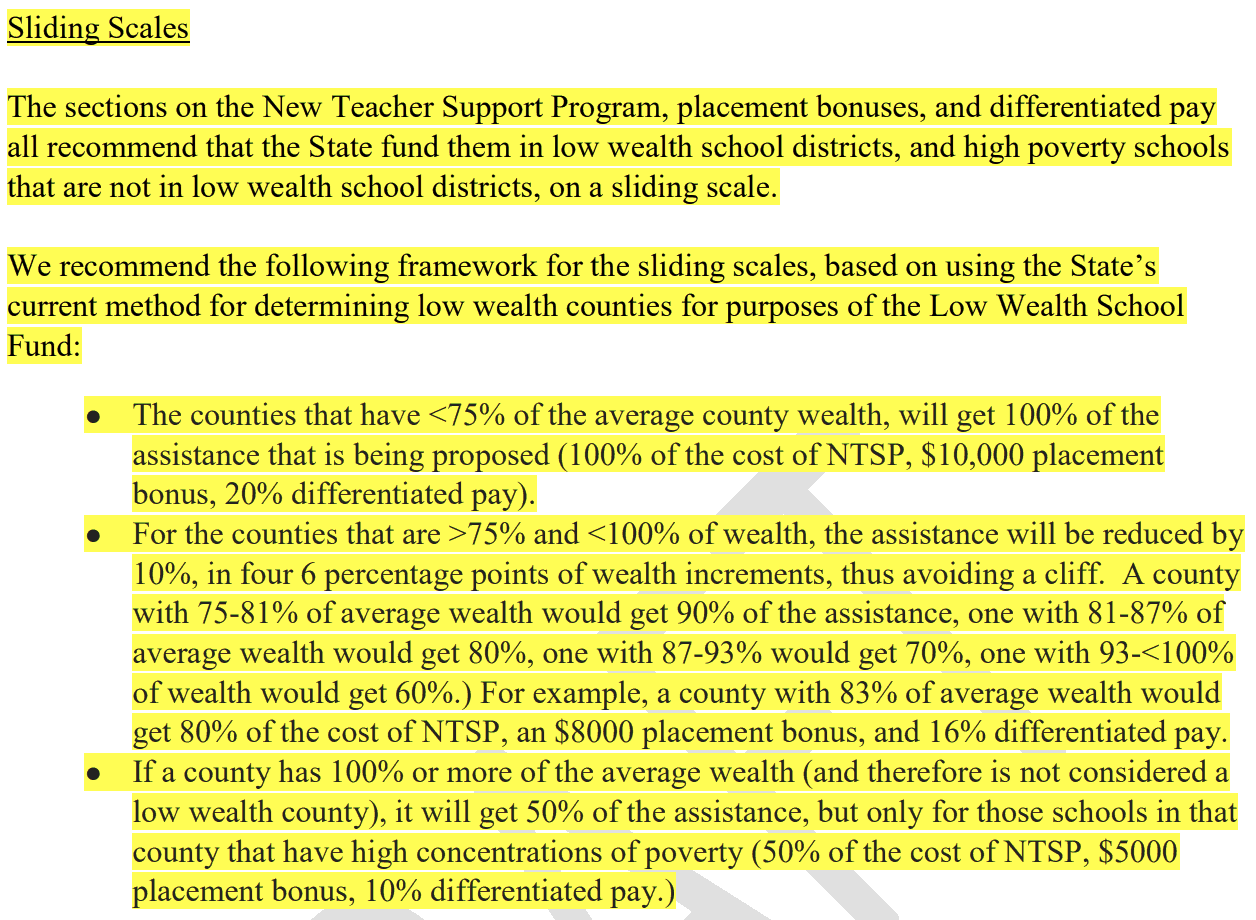

Sliding scale for differentiated teacher pay

A large portion of Tuesday’s meeting was spent discussing the teacher working group recommendation edits. One of its most significant challenges was finding creative ways to attract and retain teachers in the schools that need high-quality educators the most: low-performing and low-wealth schools.

The group’s draft recommendations span all facets of the teaching profession, including recruitment, preparation, compensation, and induction. One addition sets a goal of increasing the percentage of teachers across the state prepared at in-state institutions from 50% to 70% in the next six to eight years, with the idea that those teachers are more likely to be effective and retained.

“That would enable the superintendents and principals to be more selective in their hiring of alternative entry and out-of-state teachers and increase the quality of that pool as well,” said Winner, lead of the teacher working group.

But the biggest addition, in full below, sets up incentives for teachers to choose hard-to-staff schools based on bonuses and higher pay depending on the wealth of the school and of the county. The New Teacher Support Program is an existing program that provides professional development and instructional coaching to teachers in their first three years in the classroom. The recommendation would expand that program and have the state pay between 50% and 100% of its cost depending on the sliding scale section.

The recommendation also includes placement bonuses of up to $10,000 spread over four years for teachers who choose to work in low-wealth districts. The amount of those bonuses would also depend on the sliding scale below.

In addition, the recommendation suggests teachers who work in subject areas that are hard-to-staff or in low-wealth districts be paid between 10% and 20% more than the state’s salary schedule, depending on the sliding scale below.

The third bullet point is aimed at schools with high concentrations of poverty that are located in counties that have 100% or more of the state’s average wealth. Glazier warned against creating an incentive for individual schools to shift students from other schools in the district in order receive that money. Glazier said this could in turn lead to a more re-segregated population overall.

“Assume that you have a school that has 68% of its students that would meet the definition and 70% is what you need to be a ‘high concentration of poverty’ school and you have a couple schools in the surrounding area. There would be … some perverse incentive to redistrict some students and make that go from 68 to 70% to get the additional resources.”

Duncan said he worries teachers with no experience going into high-needs schools may not stay because of the challenging environment.

“My recollection of the data … is that it will actually hurt retention on keeping new teachers if you put them in a high-needs school if they’re not ready for that,” Duncan said.

Members also discussed the impact on other teachers at low-wealth schools that would not receive the placement bonuses given to teachers coming into the school, as well as the impact of these funds on charter school teachers.

Mark Jewell, commission member and president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, suggested some provision that encourages high school students from rural communities to go into education, who are more likely to stay in those communities long-term.

“It doesn’t do us any good to get them in college if they’re not wanting to go into field of education to begin with,” he said.

NC Pre-K expansion barriers

During the early childhood/whole child working group discussion, Henrietta Zalkind, commission member and executive director of the Down East Partnership for Children (DEPC), shared a document that outlined barriers to expanding NC Pre-K, the state’s preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds. “At-risk” is mainly dependent on family income but also takes into account factors like limited English proficiency and military status. Thirty-four percent of NC Pre-K contract administrators did not request expansion for the 2019-20 fiscal year.

Zalkind said insufficient funding is one main reason why public and private centers are not accepting funding for more slots. She shared that Head Start centers receive $400 a month for NC Pre-K slots, public schools get $473 a month, private centers that have teachers with B-K licenses get $650 per month, and private centers where teachers are still working towards their B-K licenses get $600 a month.

“It’s just plain not enough to deal with what it costs to educate those kids,” Zalkind said.

The document outlines other reasons, like sites not being able to meet NC Pre-K requirements or the requirements to be considered a 4- or 5-star program by the state’s rating system. Other barriers include a lack of qualified teachers, a lack of transportation, and a plethora of reasons why eligible children are simply not applying.

Zalkind said NC Pre-K is intended for the most at-risk children, who are also the most expensive to serve. Universal pre-K, she said, is not feasible with the current funding models and is not what NC Pre-K was ever supposed to accomplish.

“There’s a difference between eligible and universal,” Zalkind said. “We are not trying to universally serve all 4-year-olds.”

Other edits

Below are the draft recommendations for each working group. Sections highlighted in yellow indicate tweaks or additions.

Finance

Teacher

Principal