Eric Hall, superintendent of North Carolina’s Achievement School District (ASD), gave the State Board of Education a glimpse of the future of his district at today’s Board meeting.

The Achievement School District bill was passed during the 2016 General Assembly short session. At the heart of the legislation is the creation of a district which will eventually include five low-performing schools from around the state. The schools, which are yet to be named, could be turned over to for-profit charter operators.

Hall told Board members the concept of an Achievement School District has been saddled by the experiences of states like Tennessee and Louisiana, which have tried the experiment with some of their schools.

“When the General Assembly created the Achievement School District, we were looking to other states that had done some similar type work,” he said. “While those strategies have been met with mixed results, we have an opportunity as a state to redefine what it means in North Carolina.”

The legislation establishing ASDs also gave districts that participate the opportunity to pick up to three other low-performing schools in their districts to join an Innovation Zone. Schools in this zone would have charter-like flexibility but would continue to be managed by the school district.

The recently passed budget tweaked the ASD program slightly, changing its name to the North Carolina Innovative School District (ISD). It also added a provision that says if a district participating in the ISD has more than 35 percent of its schools identified as low-performing, then all of those schools could become part of an Innovation Zone should the district elect that option.

Hall, who started work in his position in May, told the board that the core values of the ISD are partnership balanced with accountability.

“When we partner, we have to do it with a high degree of intentionality,” he said, saying that partnership without accountability is irresponsible.

He said the partnership of the ISD will be with the communities surrounding the schools, as well as the students in those schools.

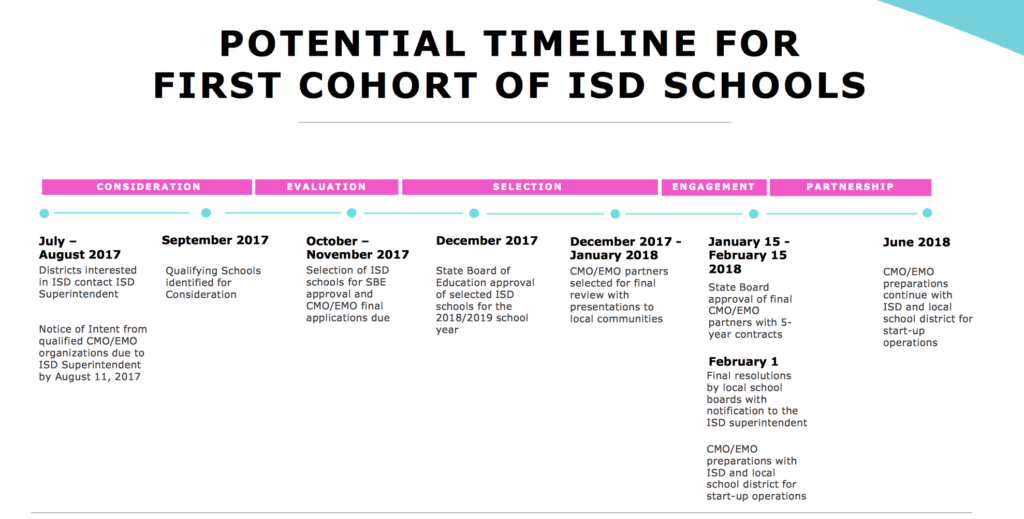

He laid out for the board the ISD process moving forward, dividing it into distinct parts. The first is the consideration phase.

“This is the part that I know a lot of folks are very interested in,” he said.

He told the Board that by September, he will release a list of schools that could qualify for the ISD according to state statute. He explained the schools on that list will be in the lowest five percent of the state and will have an elementary school component. They could be K-5 schools, K-8 schools or even K-12 schools.

“The other thing that we know we have to do is we know we have to have a cross section of urban and rural schools,” he said.

He pointed out that in other states that have tried an ISD, it always focused in one specific area. In Tennessee, for instance, Memphis was a focal point, whereas in Louisiana, New Orleans was targeted. Since the ISD will be limited to no more than one school in each district, its impact will be far less disruptive than it may have been in Tennessee or Louisiana, he said.

Hall also mentioned the school reform models — specifically the restart model — that many continuously low-performing schools want. A restart model gives a traditional school charter-like flexibility.

“If the school has adopted one of the reform models…in the previous school year, they would not be considered as a qualifying school for that school year,” Hall said.

The next step in the process will be the evolution phase, Hall said.

During that phase, ISD staff will go into different schools and conduct evaluations. As part of the process, they will meet with county commissioners, the school board, community members, and the superintendent of the school district.

“This is where we have an opportunity to build understanding,” he said.

This phase will take place between October and December. During the next phase — the selection phase — Hall will come back before the State Board with a list of schools he recommends for the ISD. The deadline for that, according to the law passed by the General Assembly, is December 15.

In a press release, Hall said he will likely choose at least two schools to be up and running for the 2018-19 school year, with all five schools open by 2019-20.

Also during the selection phase, Hall and his staff will identify education management organizations (EMOs) and charter management organizations (CMOs) who could potentially take over the schools that are chosen. He said they will go through an application process and be reviewed by external evaluators to ensure credibility.

The duration of the ISD experiment is five years, with the possibility of extension for another three years. And while the ISD will sign contracts with EMOs and CMOs for a period of at least five years, that does not mean they are obligated to remain with them, Hall said.

“We have to monitor that all along the way,” he said, adding that the ISD has a responsibility to the community to get it right.

By February 1st, the school boards in the identified districts will have to adopt a resolution that does one of two things according to the state law that created the program: transfer the school to the ISD or close the school.

“It’s in legislation, and it’s something we have to keep in mind,” Hall said.

The next phase, engagement, is when Hall said the groundwork will start to get the schools ready to open the following fall. ISD staff will be trying to nail down things like nutritional services, transportation, facilities and other things.

Next comes the partnership phase, which is basically the actual operation of the ISD for the five to eight year period.

“We are basically married in this process together,” he said.

And then there is the transition phase.

“I’ve always been taught, always begin with the end in mind,” he said.

In this phase, the ISD starts working to transition the schools back to their school districts. He said it is going to take intentional thought to figure out how to do this while taking care of parents and students.

The legislation that created the ISD gives three options for transitioning a school back to the district. The district’s board of education may adopt a resolution taking the school back. It may adopt a resolution refusing to take the school back, in which case the EMO or CMO can keep the school and transform it into a charter. Or, the local school board may close the school.

Hall was previously president and CEO of Community in Schools of North Carolina, and before that he worked as National Director of Educational Services for AMIkids Inc., which provides intervention services to youth in juvenile justice programs and non-traditional schools in various states.

“To me this work is very personal,” Hall said.

He went on to say that he has seen, through his work with youth in the juvenile justice system, what life can be like if they miss out on opportunities to learn and grow.

He sees the ISD as something that can impact the future of children for the better, and he wants the districts he will approach to know that he is not coming from Raleigh to boss them around.

“We’re not telling people what to do,” he said. “We’re working with people to find those solutions.”

Bill Cobey, chair of the State Board of Education, told Hall he was impressed with the work he has done in a short time.

“What you’ve done far exceeds my expectations,” he said. “This is one of the most well put together presentations that have ever been given to this board.”

Charter Schools

Also during the monthly meeting, the Board voted to accept a set of stipulations for Heritage Collegiate Leadership Academy. The problem-plagued school came before the Charter School Advisory Board last month and was very nearly closed by that board.

“There are a host of issues with this school, starting with a failure to submit virtually anything of significance on time,” said Alex Quigley, chair of the Charter School Advisory Board.

He said the school also had issues with its nepotism policies, in addition to other problems. He said the board decided that revoking the school’s charter immediately could be hasty, would not give the school time to correct its issues, and also might create a legal situation that could drag out the process even further.

The Charter School Advisory Board decided last month to impose a set of stipulations that the school had to meet in order to stay open.

Those stipulations include that the school needs to complete its reporting requirements on deadline and needs to either add more board members to its governing board to meet statutory requirements or dissolve its board. The school must also submit monthly budgetary and financial data, meet with the charter school advisory board two more times, and reconcile its payroll information so that it is clear how many employees actually work there, as opposed to the number listed in its payroll.

The State Board accepted the recommendation to impose stipulations on the school.

Read a detailed report of the school’s issues here.

The State Board also voted to re-appoint Quigley to the Charter School Advisory Board. His term ended last week, and when the House filed and passed legislation through the General Assembly making appointments to various bodies, it did not re-appoint Quigley.

The State Board had one open appointment it could make to the Charter Board, and chose Quigley.

“Thank you for appointing me again to the charter school advisory board,” he said. “I appreciate it. I look forward to serving.”