In Washington County, which started this school year remotely, 25% fewer kindergartners showed up in average daily membership (ADM) than at the start of last school year. Meanwhile, Superintendent Linda Carr said the district’s pre-K classes, which were held in person, were full.

In Iredell-Statesville Schools, which started with a hybrid of in-person and remote instruction, elementary schools saw a 7% drop in kindergarten ADM, a smaller decline than Superintendent Jeff James expected during a pandemic. He said 14 child care and community-based partnerships helped the hybrid model work for parents.

And in Mount Airy City Schools, which offered in-person learning five days a week at the start of the school year, kindergarten ADM grew. Superintendent Kim Morrison said it had taken five years to set the district up as a competitive option among other school choices in the area.

These three district experiences show how complicated the start of this school year was, and how much the experience varied depending on local contexts.

Overall in North Carolina, kindergarten ADM, a measure the state uses to gauge how many students are in school, dropped 15% this year compared with the first month of last school year, according to preliminary data released on October 20 from the Department of Public Instruction. That’s 16,000 fewer children.

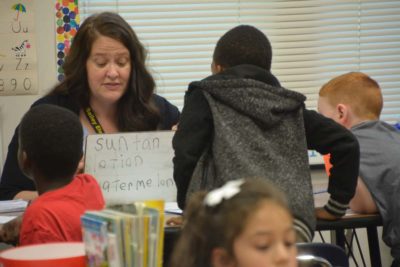

Kindergarten, which is not required by state law, had the largest drop in ADM of any grade. That’s a worry because kindergarten is a foundational year, when children get used to their school environments and gain important academic skills, experts and educators say. There are concerns over whether remote school, where about half of the state’s kindergartners started the year, can do any of that.

“Kindergarten is supposed to be an extremely enthusiastic and motivational year,” Carr said. “Parents have decided that they want to wait for that excitement.”

Disrupted transition activities

Experts say in-person activities are important to smooth the transition to kindergarten for students and families. Before the pandemic, communication and coordination were lacking between early childhood and early elementary systems. State-level education officials were working to improve that.

Carr said parents often wait until after Labor Day to register their children for kindergarten because the parents start to notice the “entire clamor” of the start of the school year. But in Washington County this year, there were no in-person orientation events, older siblings weren’t going to school, and school buses weren’t running.

“With none of that taking place, the urgency was gone,” she said.

She has held virtual community events but said attendance has been low.

“There’s still a disconnect that happens with people who are attending meeting virtually,” Carr said. “… It just didn’t have that marketing that it ordinarily would’ve allowed for.”

Though in-person kindergarten registration events weren’t possible in Iredell-Statesville Schools, James said, the district hosted a two-hour virtual event with a panel of district officials where families could ask questions about the school year across grade levels. Several hundred parents attended, he said.

And in Mount Airy City Schools, Morrison said orientation events for next school year are already under way. That means some of the outreach to parents of incoming kindergartners had begun before the pandemic hit.

And this summer, the district held in-person K-8 summer camps with social distancing and limited numbers, and had a mix of in-person and virtual registration events and tours.

Morrison said she thinks these kinds of activities — and the fact that they held camps with zero cases — made a difference in parents’ decisions to send their kindergartners to school and to be more comfortable with in-person instruction.

“When they see all of that, then I think that builds that trust,” Morrison said.

Larger landscape

Some of these numbers have more to do with population trends and local education options than anything else, superintendents said.

In Washington County, Carr said, two area charter schools have contributed to the loss of kindergartners in recent years. Job losses among a few large employers have caused some families to leave the area, she added. In the 2019-20 school year, the district’s kindergarten ADM fell 34%, even more than this year.

“So that has changed the landscape of this part of the state,” Carr said. “I would love to see it return, and I do think there’s some conversations that are happening to try to bring some of those jobs back, but … when they started laying off, it affected everything.”

The opposite is happening in Iredell-Statesville Schools, James said. A new high school with student capacity of about 1,600 is opening in the next couple of years. The district is adding classrooms in multiple elementary schools.

“Iredell County has grown economically, and we’re seeing a tremendous amount of growth in the southeastern part of the county,” James said.

In Mount Airy, Morrison said a bilingual education program, which has added a kindergarten class in recent years, plus a district-wide focus on science, technology, engineering, and math, has helped draw students back to the public school system. The district also has focused on outreach to the home-schooling population, she said.

“Families are really hungry for something different and unique that grows children but also helps them become problem-solvers, helps them own their own learning,” she said.

Pandemic reopening

In Washington County, Carr said that more than 70% of K-12 parents the district surveyed preferred to start the school year remotely. A lack of health care access has made the pandemic especially difficult, she said.

“There’s also not a large outcry from the community to return to the building,” she said.

Carr said the lack of high-speed internet access has created a barrier to remote learning, a model that is especially difficult for young children. She also thinks many parents kept their children in preschool programs or with grandparents to fit with their work schedules.

“Do I think our kindergarten numbers would’ve been higher if we opened in plan A or B? I do,” Carr said. “But our board just doesn’t feel that that’s in the best interest of our community at this time.”

Transportation is another challenge. Though this semester started remotely, Carr said, the district has communicated that when it brings some kids back in-person in January, parents will have to choose one bus stop for both pick-up and drop-off. This was a problem for parents who have their children picked up at home but dropped off at another location for after-school care.

“That creates another complex situation for the parent to have to deal with,” she said.

In Iredell-Statesville Schools, James said going back to school in Plan B, partly remote and partly in-person, was a struggle for teachers, parents, and students. Partnerships with sites that provided after-school care and full-day care for remote days were helpful for families, he said. The local United Way set up a fund to support child care needs. The district provided transportation to sites like the Boys and Girls Club and churches, he said.

“We felt like we were offering maximum flexibility, and we think when we offered face-to-face, that kept a lot of our kids in seats,” James said.

The district has now brought back its elementary students for face-to-face instruction, known as Plan A. James said teachers and parents are eager for that. In district surveys, about 80% of staff wanted to come back in-person, he said.

“The ramifications of these kids missing this much school, I don’t know that we’ll ever catch up,” he said. “(In) early childhood, we’ve got to capture them and get them to read, and that was our biggest concern.”

Morrison said low COVID-19 case rates in Surry County made it easier for the district to open in-person so early — and that’s part of the reason parents chose to send their children to kindergarten. So far, she said, K-2 classrooms have had no cases.

“School is absolutely the safest place in the community from COVID-19, and we’ve proven that,” she said.

Plus, Morrison said, the community has not been as divided as some.

“The community is a really big reason as to why we have come back, and that’s something important for people who are struggling — superintendents whose boards are divided, communities, staff, I couldn’t do any more than they’re doing,” she said.

“We don’t have to fight that fight in Mount Airy.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the location of Mount Airy City Schools. The school district is in Surry County.