A series profiling individuals working to creatively raise up North Carolina’s education system.

A series profiling individuals working to creatively raise up North Carolina’s education system.

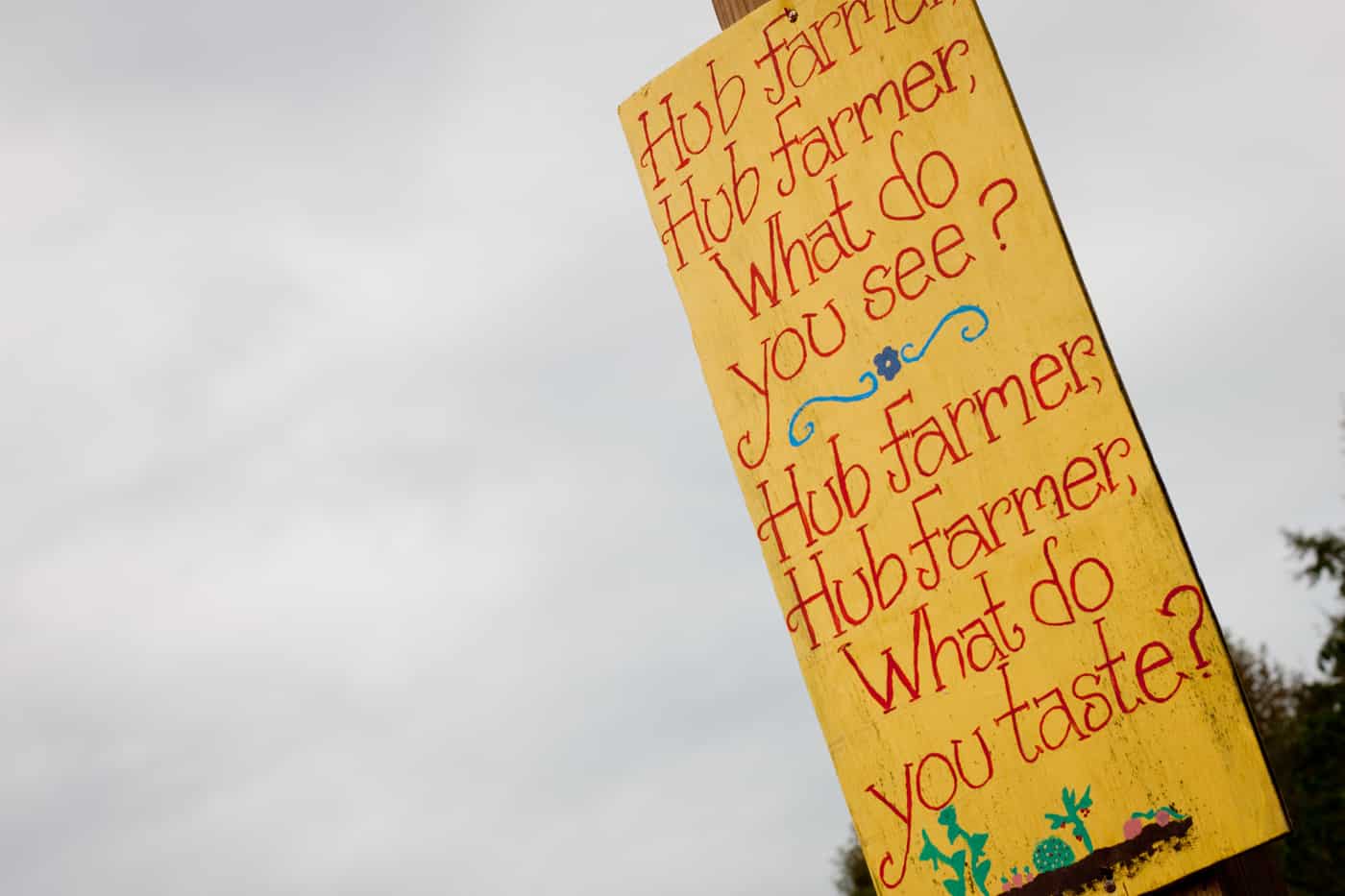

Students stream down a gravelly hill, passing chickens and an open barn door, into a clearing near a sparkling pond. Farm staff and three visiting instructors from Durham’s Innovative Nutrition Education program (DINE) have prepped spicy arugula, baby bok choy greens, and trimmings for a “rainbow salad” for their visitors from Southwest Elementary. As three eager classes line up, even the teachers breathe more deeply. Today’s lesson — on nature, nutrition, and how to explore — will be learned on the sunny green grounds of Durham Public Schools Hub Farm.

“It’s amazing how many students [come who] find even going outside a little bit foreign,” explains Hub Farm founder Katherine Gill. “They just relax.” Gill was raised in Southern Pines with frequent visits to her family’s farm in Galax, Virginia. As a child she was constantly outdoors, exploring nearby mountains, riding the family’s horses, and eating her grandmother’s figs and snapped and shelled lima beans. “I’ve always had a really strong interest in how the land engages people,” she explains. “Specifically, how it fosters creativity, exploration, and a joy of learning.” Gill applied this curiosity to a master’s in landscape architecture at North Carolina State University and is now principal at Tributary, a Durham-based firm. As a landscape architect, Gill often thinks about macro-level social issues in her work — sociology, economics, public health, and ecology.

Hear Gill describe all the Hub Farm has to offer

Hear Gill on working with the strengths of her team

In February 2012, the opportunity arose for Gill to unite her commitment to learning outdoors with these forces for greater good. Discussions about building a school system farm were developing between Heidi Carter (chair, Board of Education, Durham Public Schools), Rick Sheldahl (director, Career-Technical Education, DPS), and others, including Sheldon Lennon, then PTA president for Eno Valley Elementary School. As Gill joined in these conversations, Lennon informed the group about thirty acres of unused land behind the school. He reasoned, in Gill’s words, “Wouldn’t it be a wonderful thing if we could have space for our elementary students to come and experience what a farm is?” With that, and seed funding provided by Career and Technical Education, the DPS Hub Farm was born.

Almost four years later, Katherine and the Hub Farm team must now articulate the value of learning outside in terms the school system endorses. A walk in the woods or down a crop row with farm educators amounts to more than exploration — STEM-oriented problem solving skills are also nurtured. “It’s hard to learn math without knowing how it gets applied. But as soon as you’re put outside and you have to count how many rows of X you need to produce X, you’ve got it,” says Gill.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RiBPHoCdHjQ

Hub Farm was started to “strengthen the overall holistic health of the student for educational benefits.”

Stretching from the fields behind Eno Valley Elementary into woodlands, today Hub Farm is a multidimensional, ever-growing learning environment for students and teachers alike. There are pollination, discovery, and production gardens, a clutch of hens and two feisty roosters, up- and lowland forests, and two ponds and creeks. Since its founding more than three years ago, Hub Farm “has grown organically,” explains Gill. “We are process driven.” Staff has tripled: there are now two farmers (Reid Rosemond and Grant Ruhlan), an Americorps Service Member (Melissa Keeney), a contracted education specialist (Stephen Mullaney), and many active school members, community partners, and volunteers. Two summers ago, design students at NC State imagined, designed, and built a “floating lab” over the farm’s main pond. As Gill and her colleagues grow and improve Hub Farm, their hope is that students catch the place’s “culture of exploration.”

Hear Gill on the Hub Farm as a classroom

“The mission of the Durham Public Schools Hub Farm is to engage students in all aspects of local food production and land stewardship to foster healthy living, career exploration, environmental stewardship, and community engagement.”

Hub Farm takes learning out of the books. As soon as students leave their busses and walk down the farm’s first hill, they are encouraged to get their hands dirty, play, problem solve, and discover new things about their surroundings and each other.

On a sunny day in mid-October, Southwest Elementary third graders participated in part of the farm’s “Seed to Belly” program. This activity takes students through planting seeds, harvesting vegetables, to prepping a meal, to eating the produce and herbs they just picked. Digging in the dirt for sweet potatoes turns into a lesson on root vegetables and teamwork — and it’s also fun. “It’s like an Easter egg hunt!” laughs Gill.

Gill sees students transform in the rows of the farm’s production garden and along the winding path of its woodland trail. Curious classes encounter new tastes and smells on the farm: spicy radishes, sweet tomatoes, and the warm citrusy scent of lemon balm. Even the woods turn into a place of learning. Gill, who always walks with one eye on her surroundings, likes to speak of the “storylines in the land.” Teachers also learn at Hub Farm, and Gill has seen how a visit can “ignite why they went into teaching to begin with.”

“Suddenly [the students] realize that there are all sorts of questions and fun things to explore,” she says. “It’s not about needing something to climb on, it’s there and you do it naturally.” With one trip, students are hooked. They ask: “Can we come back on the weekend? And bring our parents?” Middle schoolers from Carrington Middle School (just behind the farm) are founding their own after-school group: the Hub Club.

Hub Farm offers a learning experience much broader than standardized test answers — and because of this Gill and her colleagues are faced with the challenge of articulating the fundamental value of the farm. “We’re up against a lot of pressure in schools that aren’t performing well, but which base success off of year-end testing,” says Gill. Seventy-six percent of Eno Valley Elementary School Families are low income, and most of the schools that the Hub Farm serves are between 50 and 60 percent low income.

“Our challenge is to take the one-off field trip and turn it into something where what they do on the Hub Farm goes back to the classroom.”

While Durham County Public Schools is supportive of Hub Farm, little funding is available and the farm has no formal administrative tie to the system. It is up to Gill and her colleagues to engage teachers. She skirts the problem of justifying a farm visit by emphasizing how Hub Farm can help teachers and students achieve their goals — on the grounds and back in the classroom. “We’re able to package things so that we’re saying, ‘Yes, we’re meeting those standards…’ But we’re also delivering it in a way that’s making [students] more conscious and aware of their surroundings.” In the DCPS work environment, everyone is pressed for time, and Gill has discovered that facetime with teachers is essential. Once they come to the farm, they’re hooked.

Hear Gill on connecting Hub Farm to DPS (00:25)

As Hub Farm enters its fourth year, Gill only has more ideas for how to improve. She’s working with her team and school visitors to strengthen the qualitative argument for support of the farm — hoping to one day embark upon a meaningful quantitative study. Hub Farm is collaborating with DPS to develop a science curriculum, and scheming about ways to get more of the farm’s harvest into the families of students. “Durham is an exciting place to be,” says Gill. She is also deepening the farm’s relationships to outside partners, including the Schools of Education and Public Health at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Gill’s greatest hope for Hub Farm is that it lives up to its name, and is the hub for spokes that connect resources and ideas to improve the school system and the local community. “I want us to be understood in the community as a lab, a place for students, teachers, and administrators to explore how we’re learning,” says Gill.

At Hub Farm, digging for potatoes and exploring the woods have immense implications for reinvigorating learning. Together with her collaborators, Gill is forging a model for learning that can serve North Carolina students in any county.

Takeaways: Words by Katherine Gill

What is the value of Hub Farm?

Students learn hands-on why things work the way they do. It’s not about getting one answer, but being able to ask a question and know what the next question will be. For teachers, it’s about getting them beyond deadlines. Let’s feed students new vocabulary, and see how that vocabulary connects in the forest and the garden. The value is in living it, living what you want to learn.

What keeps you up at night?

There is so much we can accomplish with Hub Farm. What keeps me up is how do we constantly push the envelope forward? How do tell our story, how much are we engaging students? I’m constantly thinking about what the next step is, what will bring us into the next phase of learning.

What lessons can you share?

Find out the strengths your community has, how those strengths can feed the kids, and how you can engage others in the work. Instead of asking for help, bring a lot of people to the table and ask them: “What do you need? How can we build this stronger?”

Resources

Ready to think about starting a school farm? The good work of these organizations inspire Katherine Gill.

Ready to think about starting a school farm? The good work of these organizations inspire Katherine Gill.

- Great Kids Farm, Baltimore, MD

- Edible Schoolyard Project, Berkeley, CA

- SEEDS, Durham, NC

- InterFaith Food Shuttle, Raleigh, NC

- Farmer Foodshare, Durham, NC