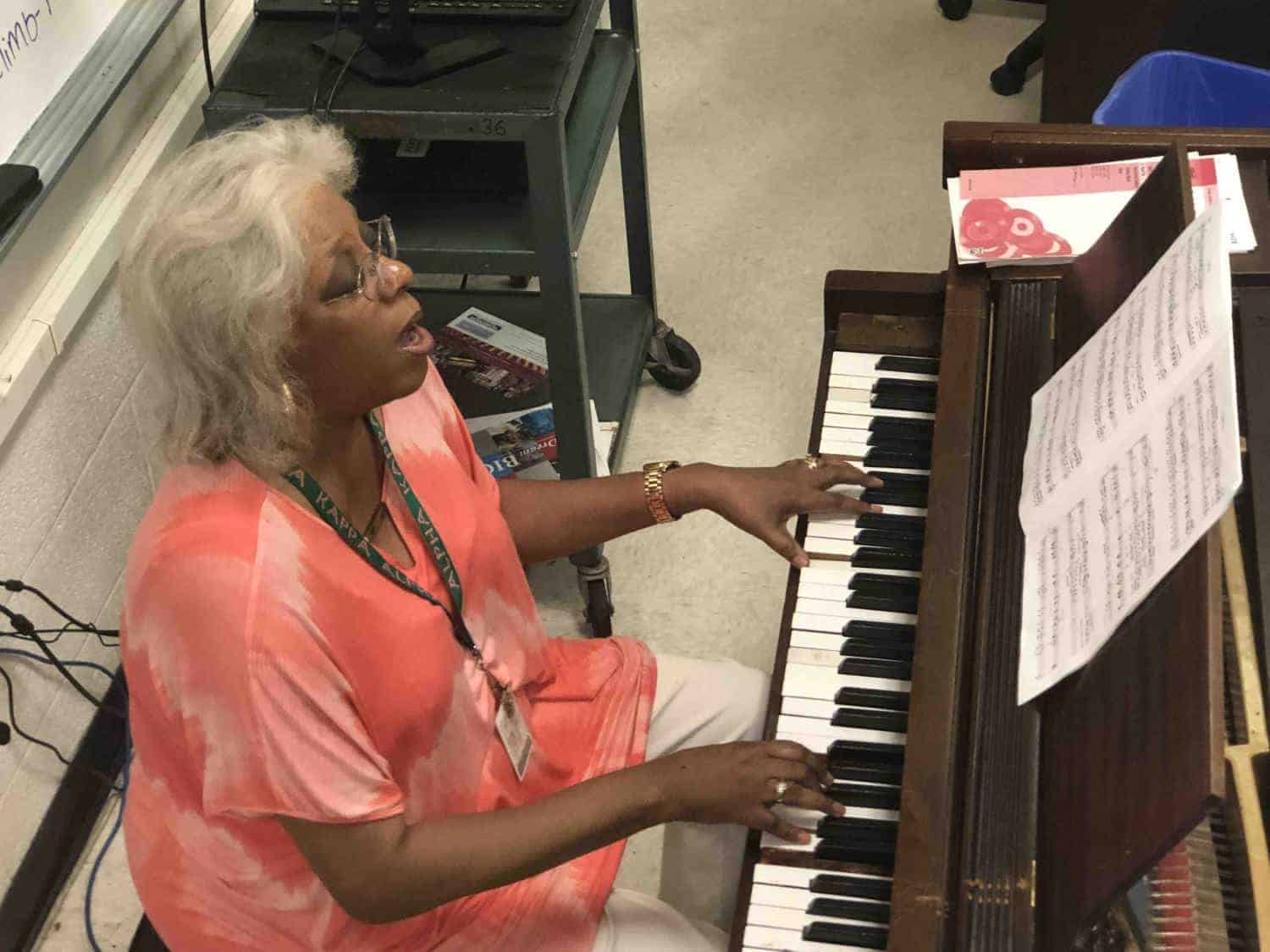

Jacqueline Robinson has spent 38 years teaching music in North Carolina schools, but it almost didn’t happen.

At one point in her undergraduate career at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Robinson was a piano performance major, but she switched to pursue music education. Her path almost veered, however, when she was asked to accompany an African-American opera singer from Illinois in a series of concerts.

It was her senior year, and she was hesitant to take the offer. It would mean taking a month off from school in January 1978.

“I was like, ‘you all are crazy. That’s my student teaching semester,'” she told them. But her piano teacher told her she was crazy if she didn’t accept the opportunity, so she did it.

She left on January 2, and for the next month played four concerts a day, an hour and a half each, in England, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. She got a taste of what it would be like to be a performer. She thought she was going to be a classical pianist. But it turned out she did not like it.

“That’s when I decided, I no longer wanted to do performance,” she said.

A life of living out of a suitcase and flying around on planes might suit some people, but not Robinson. She came back to school and finished up her undergraduate degree, and then went on to get her master’s in the same subject.

Since then, she has taught music to students from kindergarten through high school in Chapel Hill, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, and Gaston County. She has been at Hunter Huss High School, her alma mater in Gaston County since 1994.

While she may have been torn about whether to become a teacher or a performer, education has always been a part of her life.

Her mother was an English and French teacher, and her father taught classes for a Veteran Administration hospital.

“The majority of my relatives, both on my mother and father’s side, were in education. It was just either education or ministers…it was just such a respected avocation,” she said. “In church, after we moved down here from New York, our church leaders were educators. I grew up in a church where the majority of the people were educators.”

But it was more than inertia that sent her into education. It was what she saw it do.

“You know that look on a person’s face when you realize that they’ve got it?” she asked. “Their face just lit up. Their eyes. I thought, this is amazing.”

And that is the look she worked to produce in her students throughout the decades. Robinson does not just teach her students to play, she teaches them music theory and how to read music. She takes a comprehensive approach to music education.

“When my kids go places, they are some of the few who can read, they are some of the few that when conductors ask questions, they can raise their hands and answer their questions,” she said.

And beyond the content, Robinson also teaches an excitement for music. People tell her all the time that she is so excited.

“When your whole life has been positively influenced by music, why wouldn’t I be excited?” she asks.

She said music is more than just playing and listening. It is about who we are as human beings. Music does something to people that she says is indispensable.

“That’s all I’m trying to help these students understand. Whether they’re going to become music educators or not, music helps you become a better person,” she said.

While she has seen a lot of changes over the years, Robinson said technology has not done a lot to change the way she teaches. She has more to say when it comes to the political winds of change in the state education system.

She said that state leaders and lawmakers do not understand that education is one of the most important jobs there is because teachers teach everybody, including future doctors, lawyers, lawmakers, and other citizens. Robinson said she has not had a raise in years, because teachers with more than 25 years of experience are maxed out under the state system.

“I truly don’t understand what our legislators don’t understand,” she said. “There is not one life that has not been influenced by their teacher.”

At one point, a few years ago, she planned to go back and get her PhD in music education. She abandoned those plans when the state decided to eliminate the pay bump that teachers get for advanced degrees.

Despite her complaints, she is not going to the protest next week. She needs to work with her students to prepare for upcoming performances. And, she said, protests are a young person’s game. At 62, she said she is old and tired.

Her twin sister is also a music educator and is retiring this year. But when asked how much longer she plans to teach, Robinson does not give a specific answer. She says she will just decide to leave. “One day, I’m just not going to come back. Or in the middle of class, I’m just going to get my pocketbook…and just not come back,” she said.