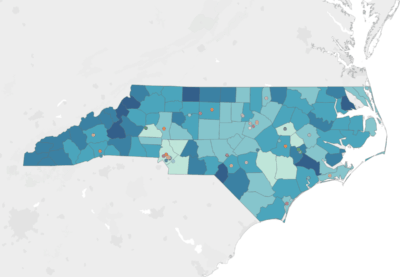

Situated at the convergence of the Trent and Neuse Rivers, New Bern was particularly vulnerable to storm surge and prolonged rain from Hurricane Florence. The city, and Craven County as a whole, saw hundreds of homes flooded, thousands displaced, and schools close for more than three weeks. Almost one year later, with a new school year underway, the lingering effects remain.

That J.T. Barber Elementary students are already in their second month of school is just one example of Florence’s lasting influence. The school followed a traditional calendar until this year, when it became the county’s only year-round school in response to lost instructional time from the storm.

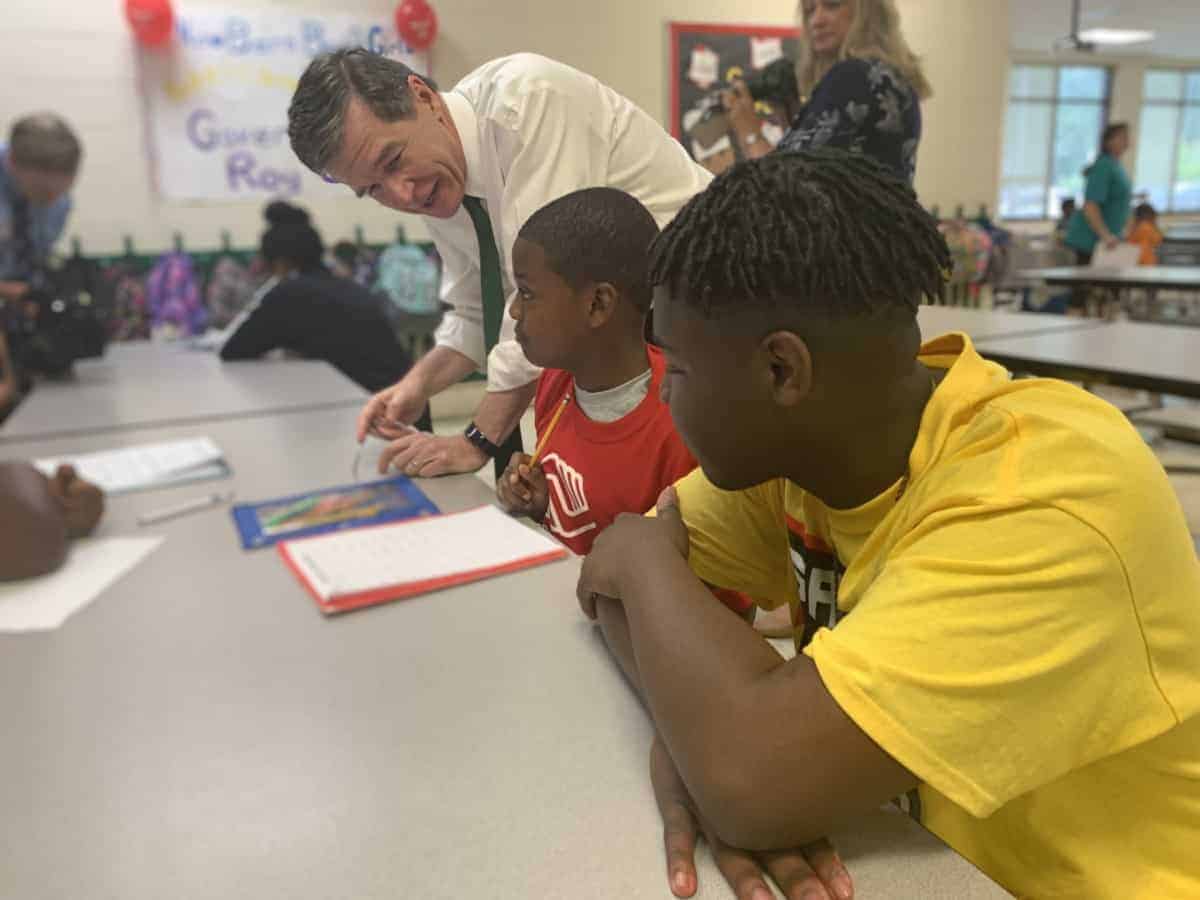

Gov. Roy Cooper visited the elementary school on Wednesday, bringing school supplies and holding a round table discussion with school and district leaders.

“I’ve been constantly amazed at how dedicated and resilient North Carolinians have been when they’ve been hit hard,” Gov. Cooper said. “I understand that this school was flooded for a period of time and you’ve had to adapt. You’ve done free lunches, you’ve moved to a year-round program to try to adapt to all of this, and incorporating the boys and girls club. What a wonderful story.”

J.T. Barber Principal Erica Phillips says they’re working on it still, but it has not always felt wonderful.

She still hears the trauma in the voices of her students. Her eyes are filled with pain and empathy as she recounts their stories. Some children say they still don’t have enough food to eat. Others still cannot live in their homes. And then there are those who remain, one year later, afraid whenever they hear thunder.

She thinks back to last year, when all you would see while standing at the front entrance of the school was flood water.

“Everything around us flooded except for our immediate school,” she said. “It completely flooded our auditorium. Everything in our cafeteria and refrigerators all spoiled. A lot of things in our classrooms we had to discard because it was full of mold. A lot of our materials and supplies we had purchased early on we had to discard. If it could not be wiped down with the Clorox, it had to go.”

At that time, teachers and administrators say it was easy to spot the impact of Florence. Now, a walk around campus shows clean walls and floors. The landscaping has been touched up. The auditorium smells of fresh paint. But the disarray created by Hurricane Florence — as well as Hurricane Matthew before it — remains in many ways, including the switch to the year-round calendar.

“We lost a lot of instructional time with our students,” Phillips said. “And there is always a huge summer slide for our students. We are low-performing and we could not afford to have a summer slide, lose all that instruction time with Florence, and then have another summer slide.”

Instead, the school canceled summer break. Moving to a year-round calendar, the school thought, would also help offset the impact of future storm-related school closings, giving teachers more time throughout the year with students.

During round table discussions with Gov. Cooper, Craven County Schools Superintendent Meghan Doyle said the idea was a popular one.

“The families wanted it,” she said.

Phillips said close to 100 of her school families were displaced and her enrollment numbers were slated to drop significantly because of storm displacement. County-wide, the school district said close to 1,000 students were at least temporarily displaced from their homes.

“Loss of enrollment was created when we had Hurricane Florence,” she said. “With year-round school, we gained some enrollment, too. So enrollment did not decline [like it would have].”

Side-stepping a compounded summer slide and substantial loss in enrollment did not ease all of the pain, though. Phillips said her school is located in a particularly vulnerable area, with many low-income residents and high levels of housing insecurity. In the nearby Craven Terrace area of New Bern, signs show that many properties remain condemned.

“Economically, they were already facing hardships,” Phillips said. “And then with Florence, it was just so much worse.”

Phillips and some of her team walked around the community months after Florence, visiting the homes of school families. She found some families living in homes where mold-infested walls were torn down and carpet was completely ripped out.

“You cannot live here,” she told them. She worked with social workers to find more suitable living conditions for those families, but she knows others are stuck in dangerous conditions because they don’t have family or friends to stay with, or they cannot afford alternative living arrangements.

For its part, the school received almost immediate help — from local churches, neighbors in the community, from other parts of the state, and from other states. They especially received support from schools in Greensboro, Phillips said, which had experienced their own storm-related setbacks and sent droves of school and cleaning supplies.

“For us, it was restoring faith in humanity,” she said. “There is so much going on in the world right now, in this day and in this era, but there are people that are out here doing good and they really want to see people be successful, be healthy, and just make it to the next level.”

The school received so much help in the immediate aftermath of Florence that Phillips and her team started focusing their asks on help for the school’s families. They put out a request to help their families celebrate a normal Christmas holiday last winter.

“It was one way we could think of to try to help them get back to normal,” Phillips said.

Wheels for Hope, an organization out of Roanoke, Virginia, responded. They donated 300 bicycles, one for each student from pre-K through fifth grade.

Normalcy is still far off, though.

Phillips said she’s noticed increased anxiety and anger among students, stemming from what she believes is post-traumatic stress disorder. Guidance counselors lead small-group counseling with some students. And the school is emphasizing compassion and mindfulness. Teachers have mindfulness time in their classrooms and guidance counselors work with each grade level once a week.

In addition to working with students, the school works with faculty and staff to make sure adults can regulate their emotions and deescalate situations as they arise.

“For the most part, our teachers just let the kids know that we love them and we care about them,” Phillips said. “It doesn’t matter how you get to school or what you come to school in — we’re going to teach you, we’re going to love you, we care for you. We’re here for you.”