It began to feel different when teachers in Edenton-Chowan Public Schools noticed their students weren’t ready to learn. Student frustration and outbursts aren’t anything new. They happen. Incidents of student anxiety and depression are frequent occurrences, too — especially during the pandemic.

But after the district engaged in community-wide surveys of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), educators wondered what lay behind these issues. What were these kids trying to say through the outbursts, and what did they need to communicate through the sadness?

“We know that in our strategic plan and we know in statewide plans we talk about eliminating opportunity gaps,” said Michael Sasscer, the district’s superintendent. “Every time a child comes into a classroom is an opportunity to learn, and we have children that aren’t accessing that opportunity. I feel — and [our teachers] feel — that responsibility to do something.”

Four years ago, the district began weaving social emotional learning (SEL) into school days to help ready students for learning. The focus has sharpened in phases over the years. SEL practices are showing up in morning announcements and lessons. Calm spaces are popping up in classrooms, with some buildings even dedicating entire rooms for them.

The next phase: Teachers are mapping SEL practices onto the state standards for every single subject across every single grade level.

Disciplinary referrals are down and teacher confidence in handling emotional dysregulation is up, the district said. And, every day, teachers are watching their young students pause and reach for strategies to calm and center themselves before diving back into academics.

“We’re trying to find a different approach to behaviors,” Sasscer said. “We’ve decided, Edenton-Chowan Schools, that we’re going to hold that torch. We’re going to go out and blaze that new path and be on the cutting edge.”

What SEL work actually looks like in a school day

It’s about 8:30 a.m. and throughout the hallways and classrooms at White Oak Elementary in Edenton, students are roaring. You won’t hear the clamor or noise, though. This is actually ROARing — a time for the White Oak Cubbies to Rise Over All the Rest.

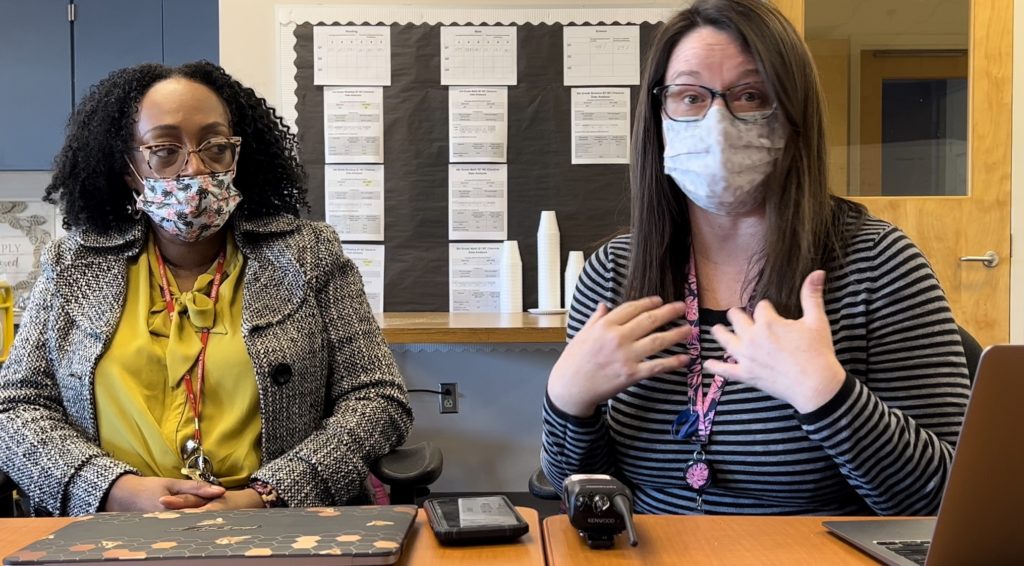

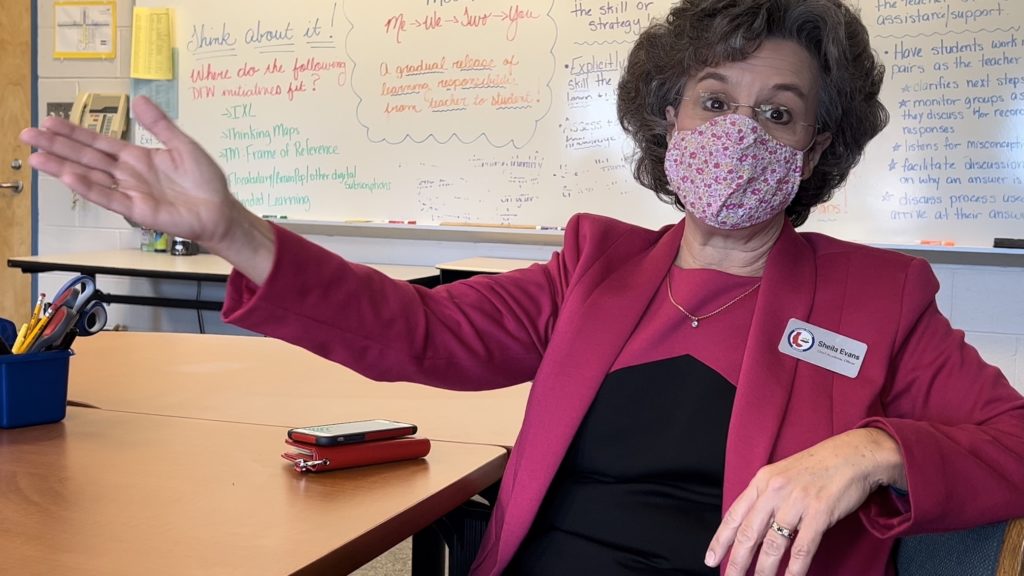

Students are getting personalized instruction and receiving academic interventions. They’re also getting help with things that might distract their minds from learning. That’s how the district’s chief academic officer, Sheila Evans, describes SEL. It’s teaching kids how to navigate childhood development and the long list of emotional responses they’ll experience. Maybe it’s the loss of a loved one, the effects of a trauma, or simply experiencing a brand new emotion.

Using the Social, Academic, and Emotional Behavior Risk Screener (SAEBRS), teachers identify students’ social emotional needs. Then they push into students’ classrooms or pull kids out for individualized support.

For some students, it means yoga. For others, self-confidence building. All of it, though, is reinforced throughout the day — with programming, curriculum, and even school culture.

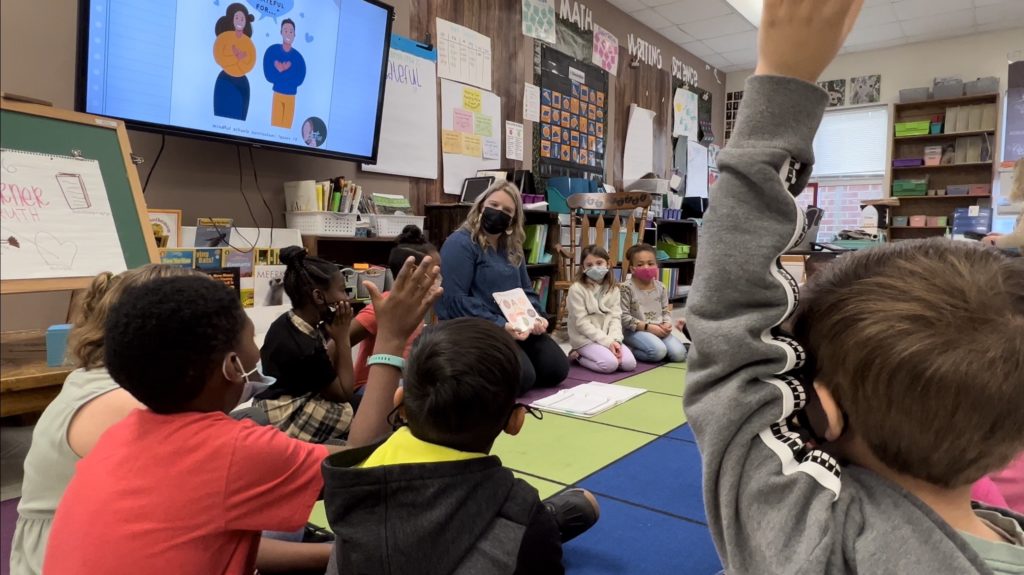

At White Oak, the school calls this work Calm Cubbies. On Cubbie TV, students learn a mindfulness strategy every Monday, and teachers practice the strategy with students each day that week.

Every week, teachers also teach a lesson from the Mindful Schools curriculum. They are working with students to add the learning from that lesson to their “mindfulness toolbox.”

The kids are breathing and finding calm, readying their minds for learning. There’s an emphasis on experiencing the safety of “now” before tackling reading and math for the next hour.

White Oak also has calm spaces throughout the school. Some are calm corners set up by teachers where students can take a break or work on mindfulness strategies. There’s also an entire calm room which students can visit with teacher approval. It’s a break from the traditional mandate of sitting still at a desk when a student simply cannot.

But it’s not just about mindfulness.

“Social emotional learning is not just having circle time or talking about our feelings,” Sasscer said. “That’s just one of the competencies, to gain self-awareness. There’s all these other skills. So how do we become intentional about those skills? We’re not interested in adding it to the plate. It needs to be seamless and integrated.”

That’s where the district’s standards mapping comes into play.

For academic learning, research shows SEL is indispensable

Several districts employ SEL strategies, but often it looks like a classroom activity that is plugged in here or there. What distinguishes Edenton-Chowan Public Schools is that the approach permeates everything happening in school. It shows up in how students start their day, what they learn, and how they see their teachers behave. Teacher modeling is important to the district as educators undergo mindfulness training to deal with their own frustrations.

Research shows that this integrated approach to SEL yields the best academic and adulthood outcomes, says Tia Kim, a developmental psychologist and vice president of education, research, and impact at Committee for Children, a nonprofit that advocates for SEL.

She cites a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Public Health. It measured social emotional competencies of students in kindergarten. Researchers then followed those same students 13 to 19 years later and found a direct connection between SEL and positive mental, emotional, and academic outcomes.

“The way that we think about it is having a really holistic view about SEL and how you’re going to teach that and integrate it within a school day,” Kim said. “I think that there’s a lot of great evidence and research that suggests that there are really good programs and, in some ways, [it’s] necessary to have direct skill instruction. But in addition to that, there has to be a climate within the school where those skills are reinforced.”

Will you take a short survey?

We’re gathering information from educators about practices and attitudes around SEL.

According to several surveys, including separate, nonpartisan polls from conservative think-tank Fordham Institute and progressive pollster Lake Research Partners, a majority of parents nationwide support the goals of SEL and many SEL practices. Still, Kim says SEL has seen attacks nationwide.

“Unfortunately, things get politicized,” Kim said, “but I think it also comes from a misunderstanding of what SEL is.”

According to the state Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) SEL web page, SEL is “a form of self-care, care for colleagues, and care for students. The same supportive system produces resilient students who graduate empowered to solve problems, communicate effectively, empathize with others, and pursue goals for further education, employment, and contribution to their communities.”

That’s in line with Edenton-Chowan’s stance. Their students experienced the effects of trauma and stress prior to the pandemic and still do now. Teachers say it impacts their students’ ability to learn, but with proper supports those same kids thrive.

“I do zero referrals,” said Brenda Holley, an instructional assistant who teaches character education, “but I put out little fires all day. It’s just healthy for the kids to know, everybody gets mad. Here’s a way I can handle that. Everybody gets stressed, here’s a way I can handle that.”

Evans, the chief academic officer, says SEL is about ensuring students and adults can move through the process of becoming aware of what’s happening to them and regulate their bodies, minds, and emotions. Ultimately, she says, it helps them find a state of calm that opens the door to academic progress — and proficiency in skills needed for future careers.

That last part is important, Kim says. Growing up is hard, but sometimes so is adulting. Employers, she says, are looking for employees who have the skills to navigate turbulence and the perseverance to do hard things.

“Look at employers – major CEOs of large Fortune 500 companies — if you ask them what they’re looking for in employees, the skills that they always talk about are really around social emotional competencies,” Kim said. “Being able to problem solve, work well with others, think critically and creatively. Even [the] military will say those are the competencies that they’re looking for as well.”

DPI is building out SEL supports for public schools. Beth Rice, a lead consultant and school-based mental health and social emotional learning specialist at DPI, says she’s paying attention to Edenton-Chowan.

Weaving practices into standards accelerates learning

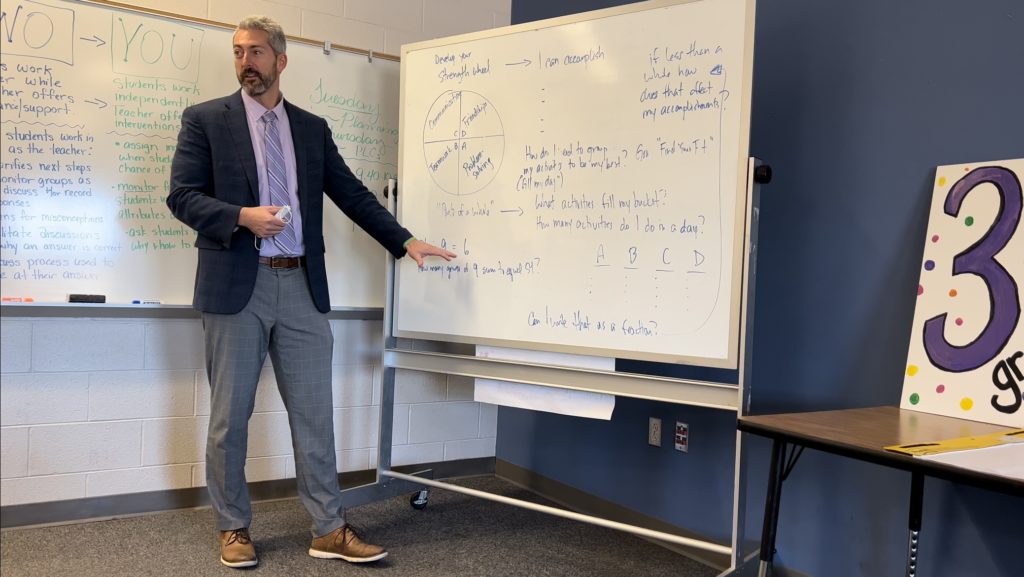

Sasscer says the district is starting phase three of its SEL work. It’s addressed self-awareness and self-management, and the Mindful Schools curriculum is a way to operationalize that. But there are three other competencies identified by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). The district wants to weave those in and then introduce practices aligned with the standards for every subject.

“We’ve talked about, early fall, introducing responsible decision-making and social awareness, [because] you’re meeting new friend groups, you’ve got new peer interactions, you’re starting to be challenged with report cards,” Sasscer said. “What do I need to do now that basketball season is starting or competition with other things that may be pulling from my academics? So that’s part of the work that’s next — to really start to be intentional in the curriculum, and then all the way down to the standard.”

If teachers are constantly leaving academic lessons to bring in SEL, they would never get through the standards. So, the district decided to layer SEL practices on top of the standards for each subject at each grade level.

Starting with the elementary schools, and then building through the higher grades, teachers are working on standards-aligned practices, or SAPs.

For example, the state standards for elementary science say a student needs to know that energy from the sun is a source of light and heat. Early versions of the SAP say that, from an SEL perspective, students should know how the sun makes them feel. Using station rotations allows one set of students to learn about energy from the sun while another group of students talk about how the sun makes them feel.

Teachers are creating SAPs throughout the continuum of learning through mastery. So as the academic rigor increases, so do the SAPs. For example, knowing what energy from the sun does is basic understanding and recall. Comparing the effects of the sun in a shaded place versus an open place challenges students one step further.

Similarly, the SAP would move from asking students how they feel when they are in the sun — basic recall and understanding — to comparing how they feel when they are cold and step into the sun versus when they are hot and step into the sun.

“So as we go through the process of extending the academic standard, we extend the social emotional learning standard,” Sasscer said. “Those station rotations advance and we accelerate learning for our students.”

The district set an ambitious goal to draft SAPs for all elementary subjects and grades by Aug. 21, 2021. To do it right, though, it quickly realized that feeding the process was as important as the end product.

“We’ve said all along that we’ve tried to move from product to process,” Sasscer said. “We want to be process proficient in what we do, and processes are fluid. Processes are ever-evolving. And I think you really want to engage teachers in an artful exercise to be creative — so as they learn and do and fail forward, they want to add and recreate and really develop something and design something that works for them.

“We need the product, but we also want to energize the process.”

As the work continues, early efforts are already paying off

The district didn’t get here overnight.

In April 2018, Chowan County was chosen as one of four communities to participate in the Institute for Emerging Issues’ KidsReadyNC initiative. Evans was on the Chowan County leadership team at the time. She remembers it leading to conversations in the district around ACEs, trauma, and healing.

The district showed the Resilience film in schools and conducted a book study around Nadine Burk Harris’s “The Deepest Well”. They also held a community-wide book study and showed the Resilience film at the local Taylor Theater.

“So many of our kids in our community have had these childhood experiences and they don’t know how to deal with them,” said Stacey Banks, who teaches fifth grade. “And this is helping us, going through this program, to teach them to process those things that are happening.”

Banks says the SEL framework the district equips her with aren’t too different from things she learned as a child. She says many of the kids in the district aren’t getting this at home. The framework allows teachers to equip students with these necessary skills.

And not just students, says White Oak Principal Michelle Newsome.

“When we went through that work, we realized that not only are our children experiencing these traumatic events, but many of the adults in our building had ACEs scores through the roof,” Newsome said. “Mine’s an 8 out of 10, so this is amazing work for me.”

“Adverse childhood experiences truly rewire[s] your brain. It changes the way your brain works, it changes the signals and electro-transmissions in your brain. So now that we know how to combat that with work such as mindful work, oh it’s amazing — not just for the children, but for adults who have experienced traumatic situations.”

The district hired Sasscer as an assistant superintendent in 2019. Prior to that, he served as principal of Manteo Middle School, where he became familiar with the work of a wellness-centered organization in Dare County.

Leela Harpur Heyder, founder of the organization Calm Minds Kind Hearts, helped Sasscer with programming at Manteo Middle School that taught students tools to cultivate present moment awareness, build resilience, and increase emotional self-regulation to promote more balanced, healthy, and joyful lives.

Edenton-Chowan Schools now contracts with Calm Minds Kind Hearts and RTI International to assist with the district’s SEL integration. The focus is moving beyond an awareness of challenges to identifying and implementing precisely what to do about it.

“We needed to find a way to bring it from that conceptual understanding to: ‘What can we do with strategies with instruction to actually help students de-escalate, regulate their behavior, and get back into the classroom?’” Evans said.

The district offered teachers an opportunity to take two training courses from the Mindful Schools curriculum, 101 and then 201. Teachers must be trained in both courses in order to teach the curriculum. The district is using Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding to provide training to teachers.

At first, it was a tough sell.

“We started the 101 last year and, to be perfectly honest, teaching in a pandemic and [being asked] to do one more thing, taking care of yourself — I did not buy in,” third-grade teacher Michelle Dewees said. “ … I loved the concept, it was just the struggle to get it done.”

After she took the 201 over the summer, though, she realized it wasn’t just one more thing to do. It was something that made all of her other work easier to do.

“It’s the real meat and potatoes of how is this going to help the teacher because it’s how do you use this in your classroom,” Dewees said. “How do you use this to address that child that comes in angry, that child that comes in hungry, that child who’s acting out because of something you don’t know. [It’s] how do you fix those things that we see all the time, but even more so since the pandemic.”

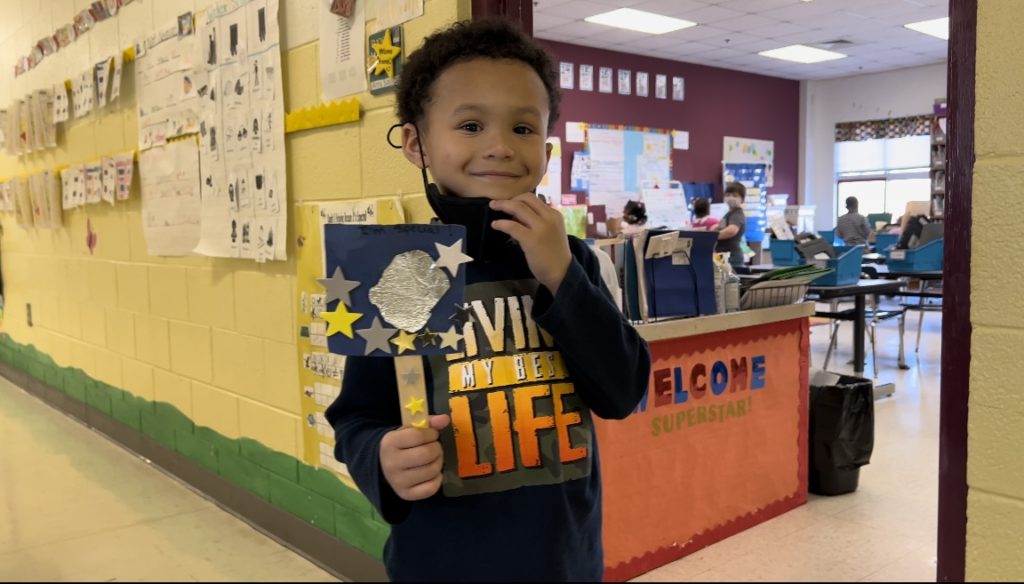

It didn’t take long for teachers to start seeing students absorb and apply lessons and strategies. In one kindergarten classroom, Jaden found himself getting angry or sad in the morning. During an art class, he made a mirror using paper and glue – decorating it with stars.

“He told me he feels sad, but then he looks in [that mirror] and it makes me feel caaaaalm inside,” kindergarten teacher Amy Sasscer said, mimicking the child’s relief in the word calm. “And the way he said it was just so powerful.”

Monica White worked with a student overwhelmed by sadness after her grandfather passed away. The student couldn’t concentrate on school work. White, an instructional assistant who teaches social emotional cultural arts, helped the student recall happy moments with her grandfather.

She spoke to the student’s parents about what happened and suggested the parents share more happy memories with their daughter to build up the student’s “happy memory bank.” Since then, the student has relayed several happy memories to White and even wrote White a thank you card.

“So I definitely get this feeling of … I did something amazing, and it’s just because I had this little tool in my pocket,” she said. “And when those [sad] thoughts come back, she says I thought about it this morning but I remembered something good.”

These are all little tools that teachers put in students’ toolkits. It may not seem relevant to learning the multiplication and division tables, but what educators in this district have learned, is that while most of their students can and will learn what 54 divided 6 equals, many of them aren’t always ready to learn it when it’s taught. Since reaching them and engaging them is a prerequisite to teaching them, SEL skills are the foundation for all the academic learning that will happen throughout the year.

“It’s fun, it’s tedious, it’s challenging, it’s frustrating,” Sasscer said of the district’s comprehensive SEL efforts. “But it’s the work that we ultimately feel will help us grow the whole child — so that we’re not just teaching 54 divided by 6.”