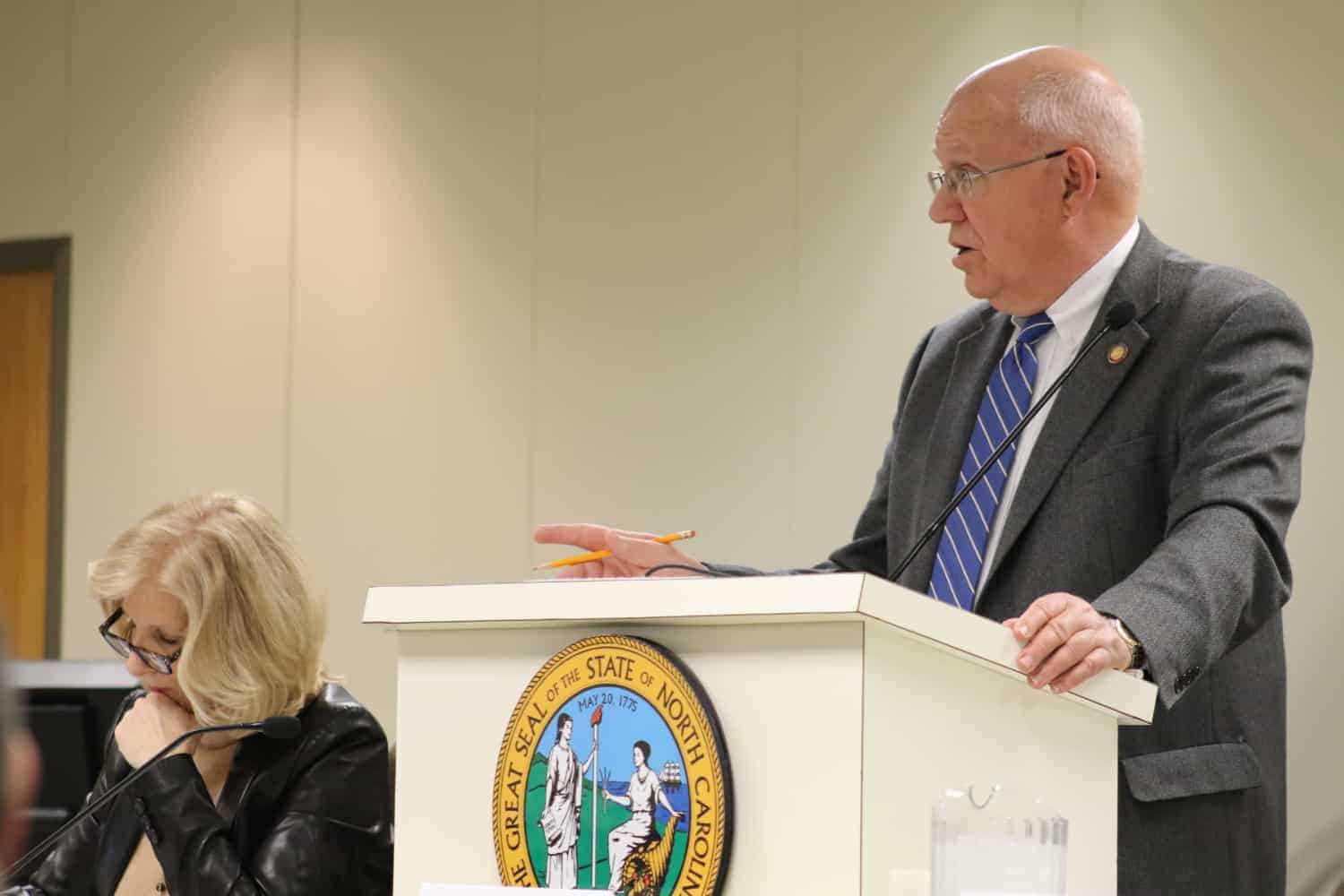

Legislators grappling with school district division are running into more questions than answers when it comes to how to separate resources and authority fairly. Rep. Bill Brawley, R-Mecklenburg, co-chair of a committee studying the consequences of splitting up large school districts, said that is the point of the group’s work.

“What we’re attempting to do in this committee is less solve the problems but to define them,” Brawley said in Tuesday’s second meeting of the Joint Legislative Study Committee on the Division of Local School Administrative Units. “This is not a trivial exercise and it deserves a great deal of study before it is seriously attempted.”

More and smaller districts, in most cases, would mean trading local independence and autonomy for efficiency and cost-effectiveness, said Department of Public Instruction (DPI) officials. Issues of equity also arose throughout DPI presentations on sorting out transportation, nutrition, technology, facilities, and staffing in the case of creating new districts.

“Is the plan fair?” said Eric Snider, attorney for the State Board of Education. “Is the plan fair? That’s going to be where the rubber hits the road for folks in districts that are perhaps working their way through this kind of process.”

The process of dividing school districts is not in current statute, meaning the General Assembly would have to enact legislation for a school district to break up into multiple districts or for a municipality or region of a school district to break off and form its own district. The second scenario is considered “secession” rather than “division.”

Kara McCraw, a staff attorney and state legislative analyst, said no new districts have been created since 1957 in North Carolina, ending a trend of cities forming their own districts. Since then, many city districts have merged back into their county systems, leaving 100 county systems and 15 city systems across the state today.

Legislative analyst Brian Gwyn said most cases of district division nationally fall under the “secession” category. Since 2000, 71 subsets of districts have attempted division from their larger districts but only 47 of those have succeeded.

“When looking at how or why the districts have seceded, the primary constitutional issue that is raised relates to the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and segregation,” Gwyn said.

Gwyn walked through a case from Jefferson County, Alabama, where the city of Gardendale wanted to form its own district separate from the county system. The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the city’s request based on racially discriminatory intentions. The court found the purpose of the city council’s 2014 decision to secede was racial motivated based partly on promotional materials and comments on the campaign’s Facebook page complaining about the diversity of its school population.

Campaign leaders, who later were elected board members, argued black students who lived outside the city and were bussed in to attend Gardendale’s schools were draining school resources without their families providing funds to the city’s schools. A desegregation order was also in place in Jefferson County which added to the court’s argument against the secession. The courts said Gardendale’s secession would impede the order’s goal.

There are differences between this case and a potential division in North Carolina. None of the state’s large school districts, Gwyn said, are under desegregation orders. North Carolina is under the 4th Circuit instead of the 11th.

Brawley said he wanted the committee to review this case because of concerns based on the state’s history.

“It’s not enough to avoid wrongdoing but I think we would have to positively pay attention to the needs of all the community and input from all because otherwise there would be mistrust,” he said. “The intent of any of our changes would be to improve education and tearing a community apart is not a way to do that.”

Sen. Joyce Waddell, D-Mecklenburg, wondered how a body might ensure a division would not negatively affect students of color.

“What measures do you have in place that would prevent that from happening — that discriminatory factors would not be the major factors in North Carolina as we move forward to breaking up large school systems?” Waddell said.

Gwyn said there are lessons to take away from Gardendale’s case “to mitigate any risk of litigation.”

A legal challenge in North Carolina, he said, would have to provide discriminatory intent since no desegregation orders are in effect. Secondly, public officials’ comments can be used to prove that intent before the individuals are in office. Lastly, a division’s discriminatory effect is not likely to prove that intent in itself.

DPI staff outlined challenges dividing school districts could bring up in specific areas. For example, making sure separate districts end up with comparable facilities — in age and quality — is important, said DPI’s school planning consultant Nathan Maune.

Creating a new transportation system requires considering how much control each district wants over bus routes and speed while making sure poorer counties have quality options, said DPI’s Transportation Services Section Chief Kevin Harrison. School district division could mean higher costs and less efficiency in the administration of federally-assisted school nutrition programs, but could also allow administrators to tailor programs for specific populations, said Lynn Harvey, DPI’s chief of child nutritional services. DPI’s Chief Information Officer Michael Nicolaides said district division raises questions around information technology like how to maintain cybersecurity in transition and how the infrastructure of the Internet can best serve districts.

Though more localized autonomy is one reason legislators are backing the idea of district division, operating funding from counties would have to be split up evenly between multiple districts. Kara Millonzi, a UNC-Chapel Hill public law and government professor, explained the current local funding structure. She said different districts within a county can request and receive capital expenses from county commissioners that are specific to its needs, but that funding for the operation of school districts must be spread out evenly among all the districts, based on student population, under current law. Districts can get around that law by using supplemental school taxes, which can bring in additional funding directly to a specific district.

“That’s the way school units, when you have multiple districts … this is kind of the way around what’s otherwise kind of the constraint of apportioning by ADM amongst the school units on the operating side,” Millonzi said.

Rep. Sarah Stevens, R-Surry, Wilkes, said she has seen multiple districts benefit the quality of education in her constituency.

“I think decentralizing some education may be helpful for competition and for attention to individuals,” Stevens said.

After hearing presentations on all the possible implications of district division, Stevens said some central authority might also be helpful to be able to use resources the most efficient way possible.

“Based on everything we’ve heard here, it looks like we could get some more economies for everybody from having some central area,” she said. “I don’t know that any of these would prohibit us from going forward with looking at smaller districts that I think are probably more functional to the students. But it clearly seems like we could combine some places to get this kind of economy we talked about on everything, between food and books and buses, you know, using them to the best scale we have without worrying about our county lines or our territories that each of our superintendents claim to have.”

The committee meets again on March 28 to discuss district size’s impact on student performance and cost.