For Victoria Fanger, a 22-year-old student at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, becoming a special education teacher was almost financially impossible.

“Basically my dad said, ‘We have no more money for college. You have to get a job, you have to drop out of college, we can’t afford it, or get a loan.'”

After transferring from Cleveland Community College, Fanger was accepted into the first cohort of the new version of the North Carolina Teaching Fellows — a program that has been around since 1986 but came to a stop when the state cut its funding in 2011. The program was reintroduced in 2017 with some changes, but still helps pay the tuition of students who commit to teaching in North Carolina’s schools.

“Through this, I’m able to come out of college without any loans, without any student debt,” Fanger said. “Period.”

Fanger said she plans to go back and teach in Cleveland County, where she grew up, after she finishes school. The program incentivizes students to work in low-performing schools by paying back one year of tuition for every year the student teaches. One year of teaching, one year of support. If fellows do not work in low-performing schools, that ratio changes to 2:1 — the student must teach two years for every year they received the loan.

When I asked Fanger why she wanted to go back to her hometown to teach, she did not mention financial reasons. Instead, she said: “At least starting out, I want to be in the community that raised me.”

She said she recognizes there are not as many high-quality teachers in smaller and less wealthy school districts.

“There’s a big push, coming from a smaller county, whenever you go to get your education to actually leave the area,” Fanger said. “It’s like, ‘Here’s a small county. You’re going to a big county. Stay here.’ And there’s a big push also at the university to stay in CMS, CMS needs help. I feel like we’re putting all of our good qualified people in CMS and then these outer-city schools are just getting left out to dry.

It’s important for me, one, just because I’m rooted in that community, and I know that there’s things that are really good and I also know that there’s things that are really bad. So I want to come back and hopefully make a difference.”

The program pays students up to $4,125 a semester, or $8,250 a year, for up to four years, and provides leadership development, networking, school visits, community service, and other opportunities depending on the school.

There are other differences between the old and new versions of Teaching Fellows, said Sara Ulm, the program’s director. First, only students who are committed to teaching in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) or special education are eligible for the program. These requirements are in statute and are meant to target content areas with teacher shortages. Students can switch between the two focus areas during the program if they want.

“That’s not just a trend in North Carolina, that’s a need nationally,” Ulm said. “For decades, those have been shortage areas, but we know that that’s a critical need for North Carolina.”

The new program is limited to five partner institutions: UNC-Charlotte, UNC-Chapel Hill, Meredith College, Elon University, and N.C. State University. Ulm said the program is hoping to add three partner institutions this legislative session. The legislature, she said, wants to move slow.

The original program selected from high school seniors before they started their undergraduate education. The new version accepts four different categories of students: 1) high school seniors, 2) transfer students from other institutions of higher education like community colleges, 3) students at a partner institution who want to switch majors to education, and 4) students who already have their bachelor’s degrees and want to get a license to teach.

“So some of them are going to be in alternative licensure programs. Some of them will be in M.A.T. (Masters of Arts in Teaching) programs. Some of them will be in traditional four-year programs,” Ulm said. “So you’re able to bring that unique perspective to the table and your own experience.”

A weekend on connecting

That range of ages and experiences were present in the seminars and group activities throughout the cohort’s first enrichment retreat earlier this month at the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching (NCCAT) in Cullowhee. The weekend was the first time the entire cohort from the five different institutions got together. One of the four missions on the program’s website sticks out when recalling the weekend: “To provide unique enrichment opportunities and experiences that focus on developing the leadership potential of Teaching Fellows and instill a greater sense of purpose, service, and professionalism.”

Ulm said she wanted the weekend to allow fellows to tap into the program’s history and community — a sense of togetherness she said she thinks is needed in the teaching profession.

“The history of the program is something that we cherish and is really important to us because there are so many who have gone before and have really set this bar of excellence that we in this room will aspire to,” she said. “But it’s also the legacy is being created day by day, so kind of finding your place in building that legacy.”

Kristen Parrish, a first-year student at N.C. State and prospective high school math teacher, grew up in Hudson. She said her experiences during the first year of the program, like learning about equitable practices in Durham Public Schools, have opened her eyes to diverse people and experiences she was not exposed to in high school.

“I have grown so much in learning about other people and learning how to appreciate other people, and I wouldn’t have gotten that without Teaching Fellows,” Parrish said. She said she was enjoying the weekend retreat — connecting with her peers at N.C. State and other institutions and learning from their views and backgrounds. But Parrish said the thing she would take away the most was how to connect to others. Growing up, she wanted to be a pediatrician because she wanted to educate young people on how to take care of themselves but did not see herself as a people person.

“I’m not a natural connector, and like [the speaker] was saying yesterday, it’s something that can be learned,” she said.

The two days of programming were centered around just that: how to build relationships with students and how to create a positive classroom culture. Why? Karen Sumner, NCCAT’s chief academic officer, said they asked the fellows.

“We know that’s important, we know that relationship-building with students is important, but we don’t have any idea how to do that,” Sumner said. “Nobody really stops and says: This is how you do it. These are tools, these are ways to make that happen.”

Sumner said the connection between NCCAT, which provides professional development to groups of teachers year-round, and the fellows’ first retreat was a natural one.

“We believe so strongly in supporting teachers that it makes sense to support our soon-to-be teachers, our upcoming teachers,” she said. “… What they are getting these two days is quite frankly knowledge, information, [and] experience that every classroom teacher needs. How incredible to have them equipped with this before they start really serious work in the classrooms? Teachers are begging for this information.”

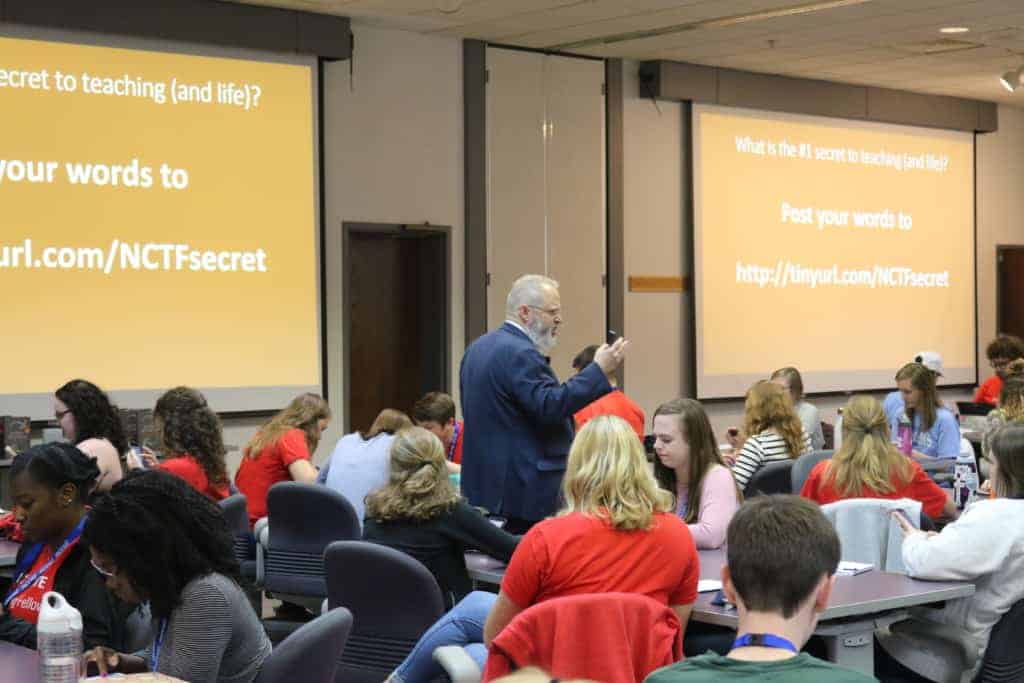

Both Albert DuPont, leadership consultant and director of UNC Laboratory Schools, and Bonnie Bolado, NCCAT’s senior math specialist, interspersed teaching and classroom management strategies throughout their presentations and group activities.

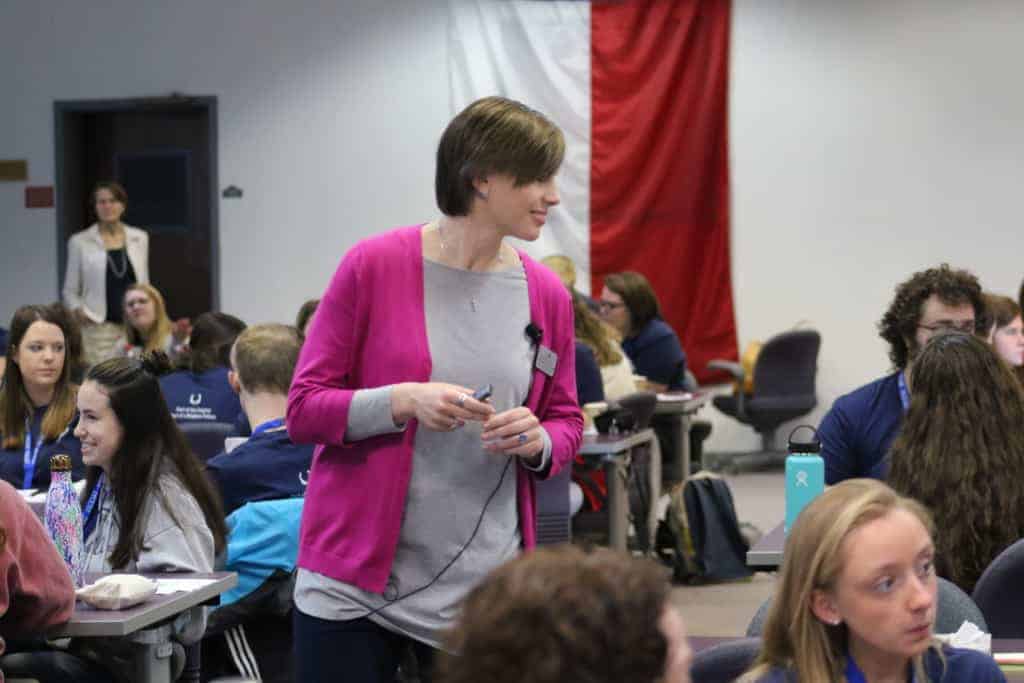

DuPont, for example, had students fill out post-it notes on what their goals for the weekend were and revisit them. He moved throughout the room quite a bit then explained how his movement signals that the knowledge is among the room instead of at the front of it.

The first night’s presentation was centered around connecting with others and how that happens. “The skills to be a successful teacher are the skills to be a successful leader,” DuPont said. He had fellows study a movie scene where a coach gives an impactful speech to his team in the locker room and had them pick out what communication skills made the coach’s words effective.

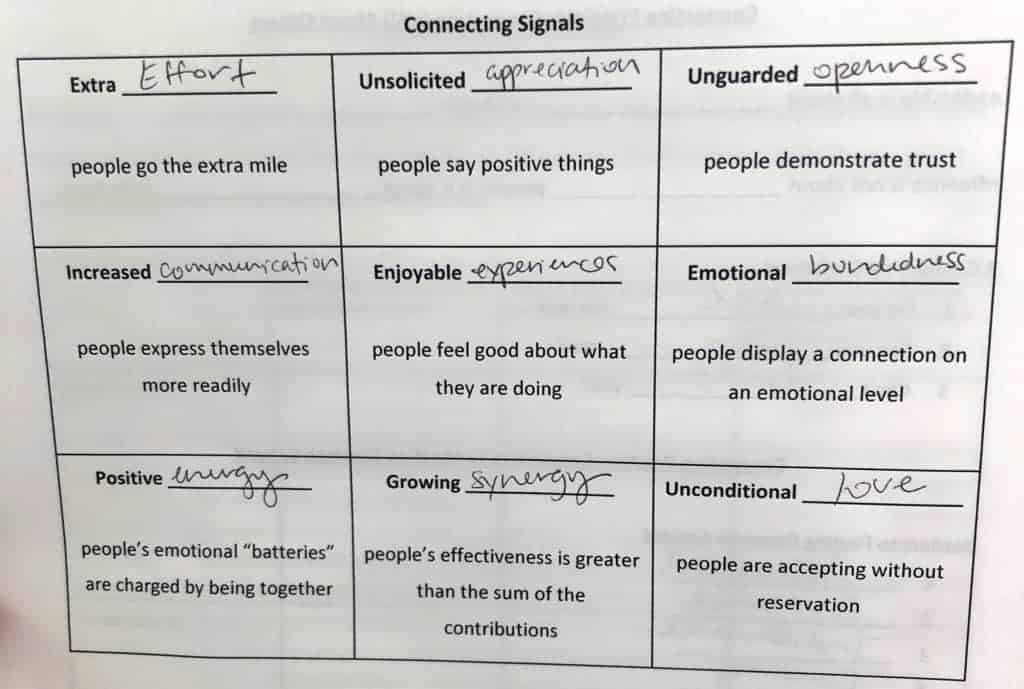

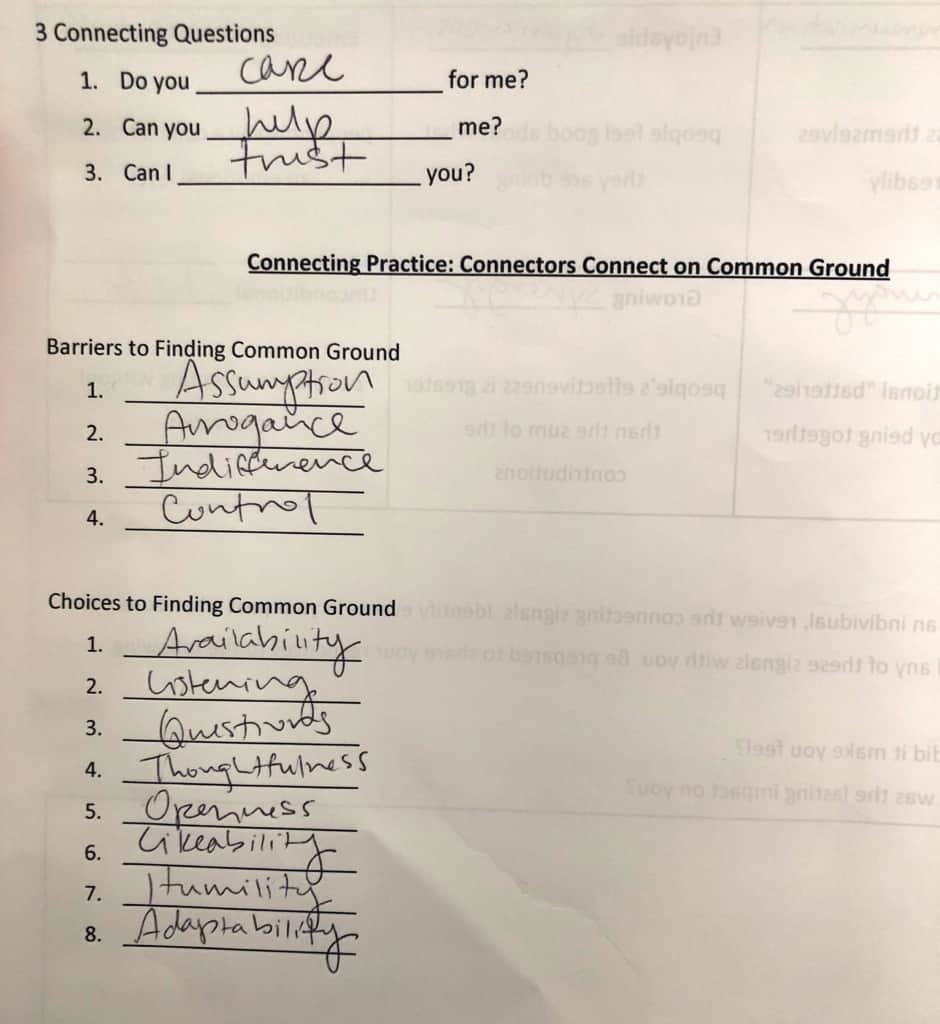

In a follow-along handout, “four steps to becoming a better connector” were laid out: great information, opportunity to experiment, great feedback, and model excellence. His main point of the night was that combining communication with connection creates meaningful relationships.

As Parrish remembered the next day, one fill-in-the-blank stated: “Connecting is more of a skill than a natural talent.”

The following broke down “connecting signals,” or aspects of relationships that form out of connecting, as well as barriers and opportunities for finding common ground.

On the second day, Bolado dove into classroom culture. She focused on the balance between building positive relationships with students and maintaining high expectations for them. The ultimate classroom culture, she said, has both. She showed a video of a high school English teacher using Humans of New York profiles to teach her students how to interview each other and build trust by actively listening to each other. Bolado’s advice was to “humanize the subject” as much as possible to make learning about people and connections.

“We have to teach students of all ages how to build relationships, have empathy, and build community,” Bolado said. “Don’t assume.”

Bolado talked about the importance of effort in the learning process and how to build a culture of effort instead of compliance.

“Here is, very classically, what students who are being compliant in the room do: They’re very good behaviorally,” she said. “They’re excellent. They’re so good you forget about them. Because that’s who they’re hiding themselves from having to be invested. And so you’re thinking to yourself, how do I get those students invested?”

Bolado suggested placing value on the “yet,” instead of the “now,” and rewarding the process of getting to an answer rather than the answer itself.

“If we truly care more about the process rather than the product because we want kids to grow, and you want to take that factor out, that rat-race to get to the answer, why don’t you give them the answer and say show me the process?” she said.

Bolado also touched on consistency and ensuring equitable teaching practice. If one student is struggling or refusing to do work, she said it helps to give them an opportunity to do just one small task for the time being while remaining consistent with high expectations for the next day.

“Don’t make your behavior expectations seem punitive,” she said. “Make it seem like they create a culture for learning.”

Sumner said these types of lessons — especially in the context of working in low-performing schools — is integral in creating successful teachers.

“They need to know what to do, and this weekend is a perfect example,” Sumner said. “It’s one thing to say, I want you to go into this high-needs school, low-performing school, and I want you to work a miracle and make this happen, but I’m not going to give you any of the tools to do so. So it’s weekends like this that make a difference. You’ve got to have that support for them to know what to do.”