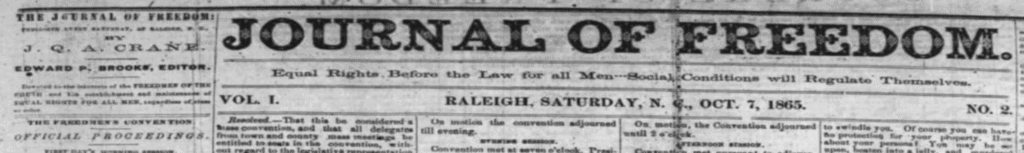

As June 19, 1865, marks the end of enslavement, September 29, 1865, marks the beginning of North Carolina freedmen collectively asserting their rights. The 1865 North Carolina Freedmen’s Convention is one of the first such conventions in the South. Held over the course of several days, the courage of these freedmen is remarkable in assembling just blocks from the state capitol and then presenting their resolution to the 1865 Constitutional Convention. A journalist who covered the Freedmen’s Convention, Sidney Andrews, describes this resolution as “one of the most remarkable documents that the time has brought forth.” Andrew further states: “This was their first political act; and I do not see how they could have presented their claims with more dignity, with a more just appreciation of the state of affairs, or in a manner which should appeal more forcibly either to the reason or the sentiment of those whom they address.”

The Freedmen’s Convention was held in downtown Raleigh at the St. Paul’s AME Church. This church is the first independent congregation for African Americans in Raleigh and becomes a center for political activity. In 1865, the church is a plain, white wooden building with the most prominent feature being a bust of President Lincoln. In total, 117 delegates attend the convention. Traveling to the convention is an act of courage itself, both for the risks to the delegate as well as to the family left behind. James Walker Hood, a delegate from New Bern, is elected president. Hood speaks to the convention:

Gentlemen of the Convention, — I hardly know how to express my thanks for the high honor you have conferred upon me; an honor I could scarcely have dreamed of enjoying. There has never been before and there would probably never be again so important an assemblage of the colored people of North Carolina as the present in its influence upon the destinies of the people for all time to come. They had assembled from the hill-side, the mountains, and the valleys to deliberate in a Christian spirit upon the best interests of our people, — holding up before God and men as our motto, ‘Equal rights before the law,’ yet understanding it to be wise and proper that, whether in doors or out of doors, we should bear ourselves respectfully toward all men. Let us avoid all harsh expressions toward anybody or about any line of policy. Let us keep constantly in mind that this State is our home, and that the white people are our neighbors and many of them are our friends. We and the white people have to live here together. Some, people talk of emigration for the black race, some of expatriation, and some of colonization. I regard this as all nonsense. We have been living together for a hundred years or more, and we have got to live together still; and the best way is to harmonize our feelings as much as possible, and to treat all men respectfully. Respectability will always gain respect, not from ruffians, it is true, but from gentlemen; and I am convinced that the major part of the people of North Carolina are gentlemen and ladies. I do not mean one class alone, but the major part of the people, both white and black. That being the case, if we respect ourselves we shall be respected. I think the best way to prepare a people for the exercise of their rights is to put them in practice of those rights, and so I think the time has come when we should be given ours; but I am well aware that we shall not gain them all at once. Let us have faith, and patience, and moderation, yet assert always that we want three things, — first, the right to give evidence in the courts; second, the right to be represented in the jury box; and third, the right to put votes in the ballot box. These rights we want, these rights we contend for, and these rights, under God, we must ultimately have.”

The Convention lasts four days with the most significant resolution being the one presented to the 1865 Constitutional Convention. This first political act leads to another Freedmen’s Convention the following year. And when the Military Reconstruction Act makes possible the election of black delegates to the 1868 Constitutional Convention, many of these new political leaders are influential delegates to the constitutional convention, including James Walker Hood, James Harris, and Abraham Galloway. The North Carolina 1868 Constitution remains the basis for education rights in North Carolina. The full text of the resolution as shared by Sidney Andrews follows – a piece of our history.

Sidney Andrews was a correspondent for the Boston Advertiser and the Chicago Tribune and traveled in the months of October, September, and November of 1865 to South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina to observe these states in the months after the end of the Civil War.

Andrews, S. (1866). The South since the war: As shown by fourteen weeks of travel and observation in Georgia and the Carolinas. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. The quote from Hood is edited to incorporate research by Eric Foner.