Across North Carolina, thousands of students attend school without a stable place to live. As local districts work to provide support, thousands more are on the brink of falling into homelessness.

Editor’s note: To protect their privacy in this story, EdNC is using the students’ initials in lieu of names.

D. is only 12, but his football IQ is sky high.

He juggles going to school, doing homework, attending practices and watching film with coaches. On some nights, those sessions didn’t end until 9 p.m. With grades being a priority, football became too much to bear and he decided to quit.

“When you get home, you knock on the door, everybody’s asleep,” says the sixth grader at West Lee Middle School, who wants to go to UNC-Chapel Hill one day. “So you just lay down and sleep.”

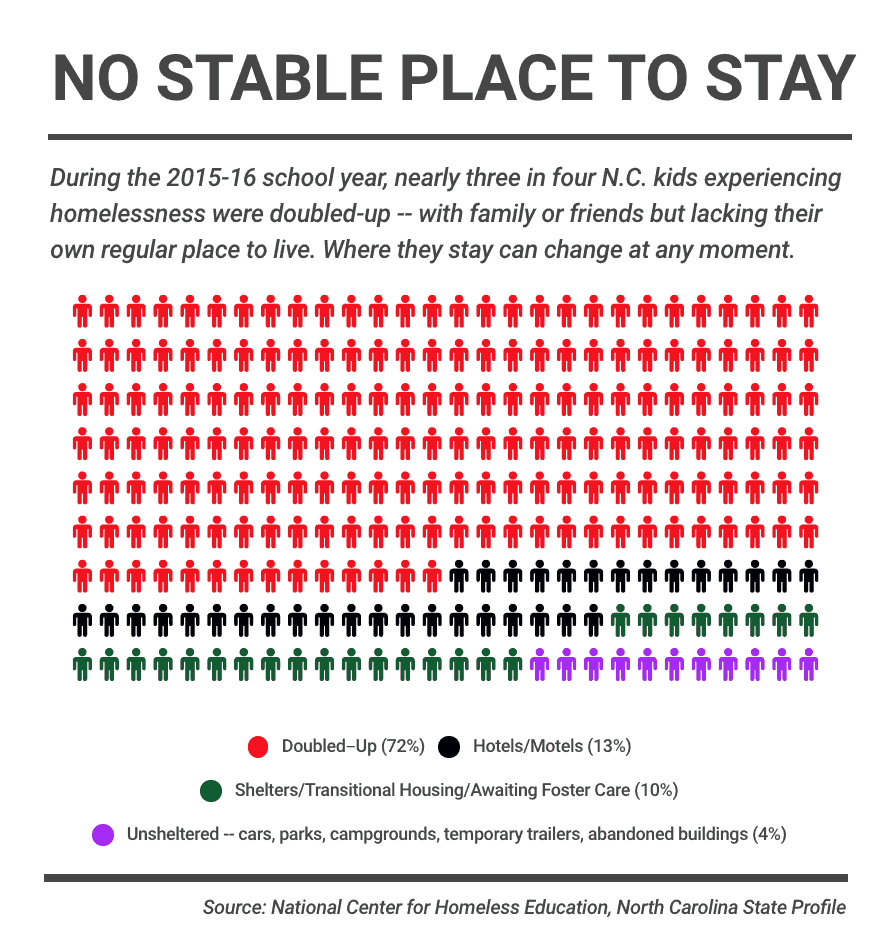

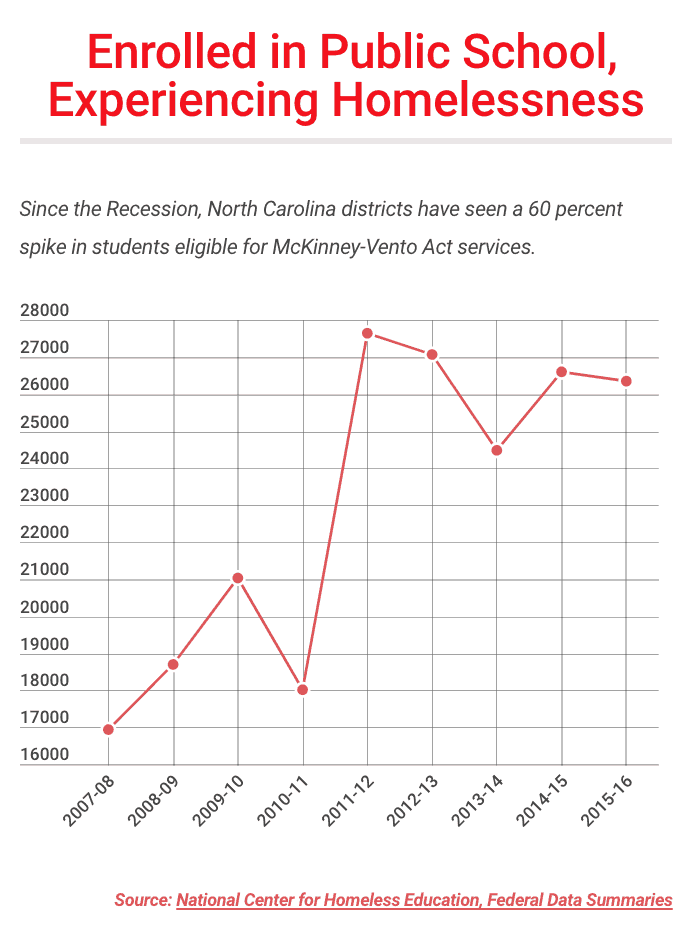

D. and his sister, N., are two of the 1.3 million students across the country experiencing homelessness. They head to school each morning, without knowing if they’ll sleep in the same place that night. Last year, around 27,000 children in North Carolina lived this reality and since the recession, the state’s population of transient students has jumped 60 percent.

N. is considering a tryout for the volleyball team. With seventh grade in high gear, the 13-year-old is enjoying her language arts class and has her eye on attending Campbell University.

On this particular morning in late October, more immediate concerns are on N.’s mind, like where she and D. will be living next. Through the first two months of school, they’ve stayed in four different rooms at two local motels. Their aunt and uncle look after them, along with their two cousins. In their current motel room, three beds are cramped into one space and N.’s 7-year-old bunkmate tends to kick.

“He does not want to get up in the morning,” she says with a laugh.

While D. and N. battle through being in transition, 22-year-old Jordyn Roark found a way forward.

Homelessness is hard enough when a parent or family member is present. For Roark, those challenges were magnified as an unaccompanied youth. Nearly 1 in 10 North Carolina children are unaccompanied, meaning they are not in the physical custody of a parent or custodian. They navigate school, housing and everything else completely on their own, in temporary arrangements that may include living in cars, parks, shelters, motels or friends’ homes.

Now a senior studying social work at UNC-Pembroke and a community outreach coordinator for the United Way of Robeson County, Roark says empathy is still lacking. She questions how any child can be expected to move up, if their basic needs are not being met.

“It’s very hard to do something as simple as a math problem when you’re not sure where you’re going to sleep,” Roark says. “Or, when you’re unaccompanied and you don’t really have anyone that you can trust or that you can fall back on.”

Services at school

Without a stable support system in place at home, public schools are a lifeline for children experiencing homelessness.

From a carton of milk at breakfast, to a box of crayons for art class, services are available to help families under the McKinney-Vento Act. Passed in 1987, the federal law mandates that children experiencing homelessness have access to transportation, meals, school supplies, tutoring and other basic needs that foster a successful public education.

“Think about them coming to school and being worried about ‘when am I going to sleep tonight?’ or ‘where are my things?’ or ‘what I have on me — is anyone going to take [it] from me?’ says Lisa Phillips, state coordinator for the North Carolina Homeless Education Program.

Nearly 30 years after the McKinney-Vento Act became law, it’s a pivotal time in North Carolina’s fight to stem homelessness. In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the law. As the national number of students experiencing homelessness doubled over the last decade, the ESSA authorized a funding increase from $70 million to $85 million annually, through 2020.

In coordination with the National Center for Homeless Education in Browns Summit, Phillips and 110 N.C. district liaisons are sharpening their focus on educating staff members to recognize students in need of assistance. Everyone from teachers to bus drivers to front office employees are involved in spotting signs.

“We feel like if we identify the students, then we can help put more services in place to meet their needs,” says Dr. Johnnye Waller, Director of Student Resources for Lee County, who also serves as the district’s liaison.

Waller says Lee County has around 300 students in transition. She cited homework, sleep and meals as examples of core areas schools pay attention to. If a student is living in a non-traditional setting, are they able to keep up with assignments? Are they getting a good night’s rest? When they come into the school building, are they in need of food?

That is because the homelessness issue is not going away. Outside of the children already identified as experiencing homelessness, a 2016 Annie E. Casey Foundation report found 209,000 North Carolina kids are living in extreme poverty.

When a few students arrive late at West Lee Middle School, the front office gently asks why. If a child is in the same circumstance as D. and N., help is only a short walk away.

Living without a regular address

On a typical school enrollment form, one of the first items students fill out is their address. For children experiencing homelessness, that basic detail is wrought with complexities.

Under the federal definition of homelessness, students who qualify for McKinney-Vento Act services lack a “fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.” At both state and federal levels, around three-fourths of these children are in doubled-up settings, sharing a temporary roof with friends or another family. D. and N.’s living arrangement falls into this category.

At morning check-ins with the children, Lee County Schools Social Worker Peggy Mann learns another move may be coming. When a student’s living situation shifts from day to day, school staff members like Mann need to know about any changes. Without a heads up, they’re on the front lines of trying to find where the child may be — both for basic emergency contact information, as well as the continuation of McKinney-Vento Act services.

“I come looking for you when you’re not here, don’t I?” Mann asks D.

“She hunts me down,” he replies with a smile.

“Only because I love you,” Mann says. “I want you to succeed and be here.”

Mann is one of six school social workers in Lee County. In larger districts like Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, where more than 4,000 students experienced homelessness, some schools have dedicated social workers to help eligible McKinney-Vento Act children.

At Garinger High School, school social worker Yvette Watson received one of those team members for the first time in mid-October. From intake sessions to home visits, Watson says having additional staff in place matters when working on dozens of cases. Asking for help may not always be the first thought on a family’s mind.

“In the crisis, a lot of times, the parents don’t call the school right then to let you know what’s going on,” Watson says. “They’re basically trying to figure out ‘where am I going to be?’”

Getting to school

As a family grapples with the uncertainty of that question, the child does not have to change schools.

The McKinney-Vento Act grants students the right to stay at their “school of origin” — the last place where the child was learning before entering a transient housing situation. When a move takes place, liaisons work with individual schools and families to sort through options. If the school of origin is in the child’s best interests, McKinney-Vento requires that transportation be provided by the district.

Since kindergarten, N. estimates she and D. have cycled through seven schools — six in Lee County and one in Chatham County, where they lived with their father for a short time. N. tells Mann she and D. may be headed back to East Lee Middle School, which is around 10 miles on the other side of Sanford.

“Almost every year, like fifth, sixth, whatever grade, we always moved schools,” she says.

At the late October check-in, N. lets Mann know they will be in their current motel room for at least two more days and probably move over the weekend. Despite all of the transitions this year, Mann still makes sure N. and her aunt will keep the school in the loop, so they’re aware of their McKinney-Vento Act rights.

“I know, that’s hard on you, I know,” Mann replies when she learns of the potential school change. “That’s what we don’t want to happen. That’s what we try to keep from happening. That’s why if you want to stay, make sure she knows you’ve got that option.”

This year, N. already had to miss two weeks of class at West Lee because she did not have some necessary immunizations. She managed to keep up with her schoolwork and maintain good relationships with her teachers.

“I kind of do want to stay here,” N. tells Mann, recognizing she would have to adjust to a whole new set of classes and teachers if she leaves for East Lee.

No matter what happens with their school choice, D. and N. appear to be staying in Sanford. But even if a student ends up moving outside of the area, the district where the school of origin is located arranges some form of pickup. As an example, Waller says Lee County has had a handful of students move to nearby Harnett County. These situations may require coordination across county lines for services like transportation.

For larger counties with longer distances between school and transitional housing, logistical and fiscal challenges emerge. In Guilford County, the rule of thumb is the transportation process takes no longer than three days to set up. But Yatisha Blythe, Supervisor of Homeless Services & Community Support, says that in a district as vast as hers, with 72,000 overall students, each case varies and the process can be tricky at times.

Last year, Blythe worked with more than 3,000 students who were experiencing homelessness. A family move from one end of the county to the other would require individual attention to find a bus route solution. Blythe says sometimes Guilford County Schools eats costs.

“We don’t want kids having to get up at 5 o’clock in the morning just to get on the school bus, so that they can get transportation to get to school by 8 o’clock,” she says. “That’s just too many hours spent.”

Living alone altogether

For unaccompanied youth, transportation only scratches the surface of day-to-day tasks that can grow complicated.

These students are often high-school-age children who may have undergone some form of family dysfunction, including neglect and abuse. Some leave their families on their own accord. Others are asked to leave because their parents can no longer take care of them.

At age 15, Roark fell into homelessness as an unaccompanied youth in Kill Devil Hills. She dropped out of high school at age 16 and moved around in a few doubled-up situations. Without a parent or guardian by her side, she pretty much avoided anything that required a signature.

“If that meant not going on field trips, I didn’t go on field trips,” Roark says.

Two years and 250 miles later, desperation was settling in for Roark. She was now living in Brunswick County, with another family she had met. While turning 18 lifted the signature burden off of her shoulders, she wanted to finish high school.

Roark made a critical call to North Brunswick High School and asked to enroll. She was up front about experiencing homelessness and needed help.

“I hadn’t been as honest before because there was the burden of stereotypes and people’s views of you,” Roark says. “And when you’re under 18, the fear that like social services is going to step in and take you into foster care.”

The same week Roark enrolled at North Brunswick, the guidance counselor who had picked up her call left for a different school. That’s when another guidance counselor, Ann Mayberry, changed her life.

Getting to college

Mayberry, who recently retired with nearly 40 years of experience in the North Carolina and Virginia school systems, sensed Roark was smart. Roark says Mayberry told her “we can do this” and walked through resources that were available.

Straight As were no replacement for a stable support system. The family Roark had been living with was evicted and forced to move out of the area. There were no shelters in Brunswick County. If she had to move to the next county over, she feared she wouldn’t be able to get to school.

Roark leveled with Mayberry, telling her: “I know that I won’t be successful.”

Since Roark was already 18 years old, Mayberry convinced three teachers at North Brunswick High School to let her live with them. They all helped take her to and from school. If Roark didn’t have clothes or groceries, Mayberry helped buy them. Mayberry also connected Roark with a part-time job through a workforce development program.

As one of the older students in the high school, Roark says she did not have a lot of friends. So she ate lunch each day in the guidance counselors’ office. Whenever college representatives came to visit, Mayberry pulled Roark in to listen. Mayberry knew Roark could obtain a Pell Grant and during those lunch sessions, she put stacks of scholarship applications in front of her.

When Roark graduated from North Brunswick High School, her teachers threw her a party, complete with dorm supplies. Mayberry then introduced her to another student, who had a family but also experienced homelessness. They became roommates at UNCP and have been competing for the highest GPA in their department.

Roark knows her story is one that most students do not have, which drives her to be a voice on eradicating homelessness. McKinney-Vento Act services stop as a child enters higher education and she continues to climb past not having a traditional family support system. For the college dreams of D., N. and thousands of other children in these circumstances, Roark thinks something has to change, starting with more funding.

“Organizations and individuals need to think outside of the box to start fulfilling these needs for students that seem so small, but make such a difference,” says Roark, who is interested in creating a nonprofit that helps college students receive dorm supplies, just like she did.

While Mayberry is retired, she recently helped two boys in Brunswick County with their college applications and financial aid plans. She knew the family and suspects they weren’t aware of the McKinney-Vento Act.

Without Roark’s honesty, she might not have known either.

“I just think it’s an embarrassment for a lot of people,” Mayberry says. “And I think that’s a stigma we have to overcome because bad things can happen to anybody, until people can get back on their feet.”