Share this story

|

|

Last week at Vanceboro Farm Life Elementary School in Craven County, the lunchtime routine looked a little different.

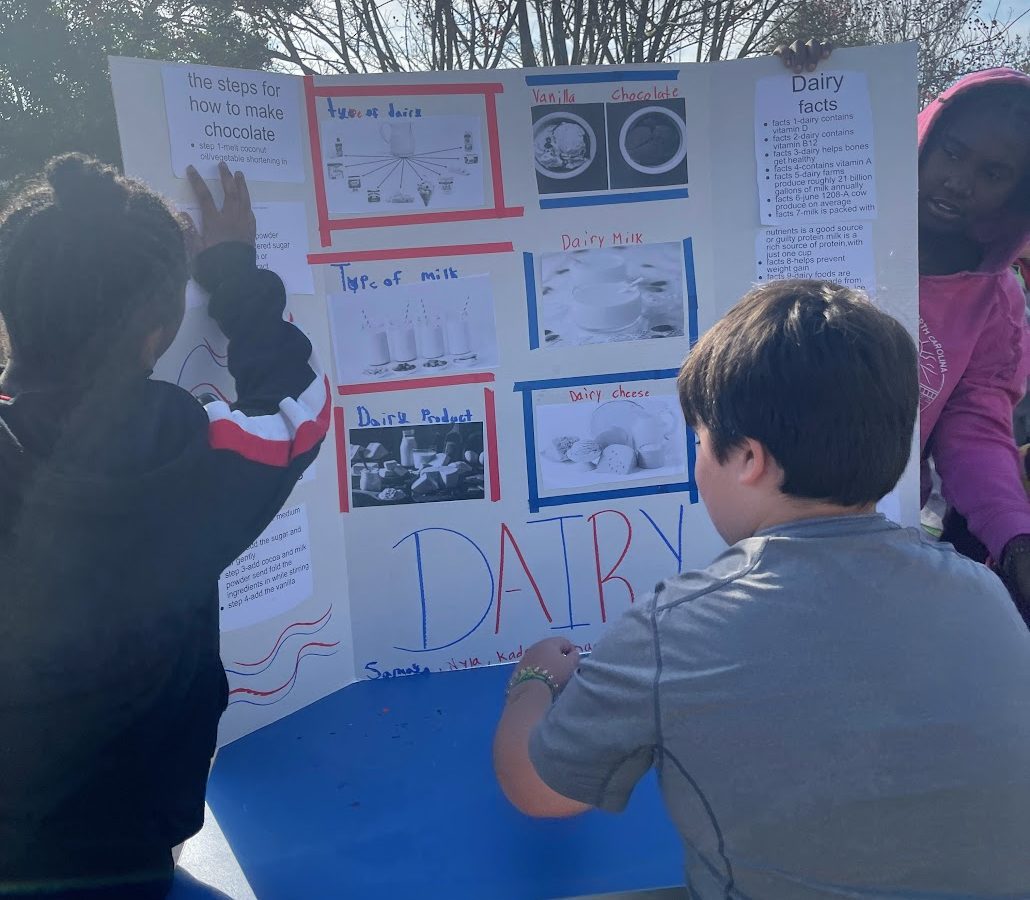

As culinary students from West Craven High School served individually portioned test kitchen recipes they made, they were flanked by fifth graders in the school’s courtyard presenting research posters to their younger peers about healthy food groups.

“Here’s a myth, that ancient grains have no taste,” said one fifth grade student presenting on the grains food group, pointing to her poster. “But the fact is that ancient grains can be seasoned deliciously!”

Over by the beef section of the test kitchen, local rancher Kristen McCoy of McCoy Cattle Farms in Cove City fielded some tough questions from students about how the meat was sourced for the beef tips displayed next to her.

“You killed a cow?” one student shouted upon learning that one of her very own cows, pictured on the students’ research poster, may have been a source for today’s meal.

“We have a whole bunch of cows,” McCoy said. “And that’s how we can make sure everybody can eat in our community.”

October was Farm to School month across the country, and Vanceboro Farm Life Elementary’s Farm to School Fun Fest held last week served to mark that occasion.

Craven County district and school officials sourced local foods and helped students to develop and test recipes that are healthy and palatable for school meals. The day also included an educational component that taught students that eating from healthy food groups is important for their health – and delicious, too.

“We really try to change the way kids see food and the community sees food,” said Craven County School Nutrition Director Lauren Weyland.

What is Farm to School?

Farm to School’s primary goal is to help school districts develop stronger relationships with local growers so that locally sourced food can more easily be incorporated into school meals.

In Craven County, Weyland has worked hard over the past several years to foster strong relationships with local growers, especially in light of supply chain issues impacting school districts’ ability to procure food – and her efforts have paid off.

“Now more than ever, having built those relationships with our farmers, we haven’t missed a beat in terms of missing out on (food) items for our kids,” said Weyland. “A lot of districts complain ‘I can’t get this, I can’t get that,’ but I will use our local farmers.”

There’s a statewide coalition working to make it easier for districts to source locally grown food for school meals, particularly from smaller farmers and farmers of color.

And last month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded the N.C. Department of Agriculture more than $5.6 million to expand Farm to School efforts like those in Craven County.

“Creating more opportunities for North Carolinians to source local products from North Carolina farmers is beneficial all around, for consumers, farmers and our local food supply long term,” said N.C. Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler in a press release announcing the award.

Lynn Harvey, director of school nutrition services for the N.C. Department of Public Instruction, said this is great news for North Carolina’s Farm to School program.

“More money for the purchase of locally grown products will help alleviate supply chain issues,” said Harvey. “North Carolina has the most unique farm to school program in the nation – and there’s latitude for school nutrition directors to directly purchase food from local farmers.”

Making it easier to get locally grown food into school cafeterias

Working with local growers is not as simple as placing a bulk order for beef, for example, and seeing that order arrive a week later. Extensive meal planning and relationship building must take place in order to feed beef tips, for example, to a district of thousands of kids. A grower like McCoy Cattle Farms would need years, not weeks, of a heads up in order to raise the cows and get them ready for slaughter.

School districts also need to keep in mind that growers try to cultivate contractual relationships with multiple consumers, diversifying their consumer base in case one client suddenly disappears. So when a school nutrition director places an order, they have to be mindful that they cannot ask for an entire crop of a vegetable from a grower if they can’t commit to asking for that same order year after year. It’s a complex dance.

Another barrier that smaller farmers sometimes encounter when trying to ensure their products are school-ready is something called GAP certification. GAP stands for Good Agricultural Practices, and it’s a regulatory mechanism to ensure that students are eating food that is grown in healthy settings. However, it can be costly, making it a barrier for some smaller farmers. The new federal grant could potentially defray some of that cost, depending on how it is implemented, so that smaller farmers can participate in Farm to School efforts.

Harvey said there’s even more support coming down the pipeline to address some of these barriers: in addition to the NCDA award, DPI also received last month a grant from the USDA for $1.5 million to work collaboratively with NCDA on farm to school initiatives.

“We look forward to working with those small farms, in conjunction with the NCDA, to help them build farm cooperatives and to build the capacity to help small farms bring greater volumes of products into the school nutrition environment,” Harvey said. “This is something we’ve wanted to do for a long time, we just haven’t had the resources to do it.”

School meals are healthier today, and farm to school efforts can give an even bigger nutritional boost

Back in the 1990s, federal nutrition standards for school meals were not as robust as they are today.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture requires schools to comply with strict standards that were redesigned in 2012 requiring more fruits, vegetables, and healthy grains than in years prior.

The result? A 41% increase in the nutritional quality of school lunches between 2010 and 2015, according to a 2019 study from the USDA. And a 2021 study by Tufts University found that schools were the single healthiest place that children consumed food, with grocery stores, restaurants, entertainment venues, and food trucks all offering meals with lower nutritional quality. As a result, this also sets students up for success in the classroom.

But it can be tricky for districts to meet the strict nutritional standards today when supply chain issues that have developed largely due to the global pandemic make for unpleasant surprises. Sometimes an order suddenly can’t be filled because a grower or distributor can’t get the supply that is needed for school meals that were planned out months in advance.

That’s when you need a Plan B in place, Weyland said.

“If USDA wants us to keep building those bridges between local farmers and school districts, then they have to realize that they have to have some flexibility in there for us,” said Weyland. “They have to realize that we’re trying our best, and if we didn’t meet the meal pattern for that day because we weren’t provided what we were told [we would receive] then it’s okay.”

As Weyland looks forward to future Farm to School events, she said she’s thankful for the partnerships she has with local growers like McCoy Cattle Farms, because they will increasingly allow her to develop meal plans months and years in advance that will incorporate more locally sourced ingredients.

“We’re figuring out the math now to add their beef with locally grown rice, and I think that will be a great menu item,” said Weyland.

With time, relationship building, and more financial support for Farm to School efforts, school districts’ ability to depend on locally grown foods could become something that students can come to expect as even more of a consistent feature on their plates each week.