In this special report, EdNC looks at how the pandemic impacted education and what that means for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

It has been a wild year for teachers, students, parents, and superintendents — basically anyone involved in education. Back in March 2020, Gov. Roy Cooper announced that all schools would close for at least two weeks, beginning the state’s experiment with remote learning. That two-week period was extended, and in April, the governor announced that schools would be closed for the rest of the year.

Since then, the pandemic has put every aspect of K-12 education to the test, and major trends have emerged that could have a lasting impact on the future of education. Below, we explore the impact of the pandemic on different parts of K-12 education, including enrollment and attendance, literacy, social and emotional supports, standardized testing, broadband, tutoring, discipline, infrastructure, and nutrition.

Share your thoughts with us by tweeting with the hashtag #PandemicSchoolYearNC.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Fewer students enrolled and attending

By Alex Granados

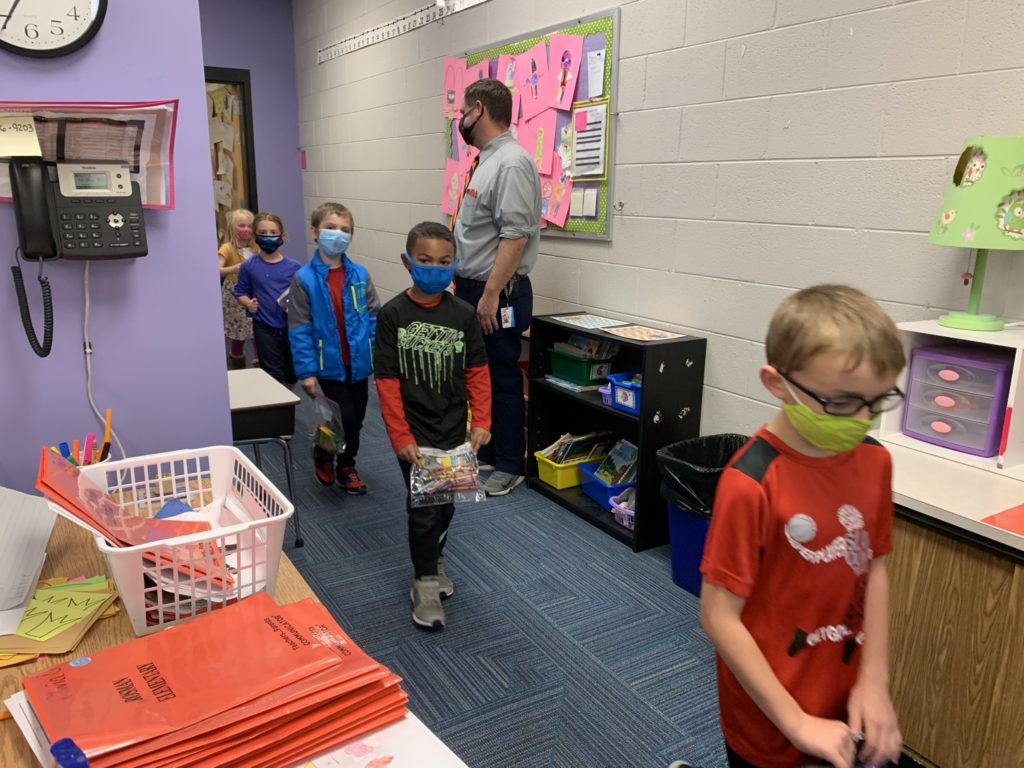

Remote learning has had mixed reactions, but last spring it was generally agreed that the governor’s decision made sense. The big question over the summer, however, was what would happen in the new school year. In July, Cooper announced that schools would operate under plan B in the fall, which would let schools open under a reduced capacity and use a hybrid model of in-person learning and remote instruction. Districts also had the option of opening under plan C, which would just continue remote instruction. Full-time, in-person learning was off the table.

In the fall, Cooper relented on elementary school students, allowing them to return full-time in person if districts wanted them to.

Then, nearly a year after schools closed, Cooper reached an agreement this past March with lawmakers to allow districts to return all students in person, full time.

The fallout from all these changes has been lowered attendance and concerns about enrollment. Leading into the fall, school districts and education leaders were anxiously asking the legislature for a “hold harmless” on their Average Daily Membership (ADM). The ADM is a measure used to get a snapshot of how many students are in schools, and districts are funded by the state based on their projected ADM. If the actual ADM is lower than projected, districts can face budget reductions. A hold harmless would prevent a funding cut.

Back in September, lawmakers granted that hold harmless to districts.

According to Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography at the Carolina Population Center at UNC-Chapel Hill, in the second month of this school year, almost 63,000 fewer students were in the state’s public schools. That’s a 4.4% decline from the year before.

In March, Tippett wrote that public school enrollment has been going down since the 2015-16 school year, largely because of increased enrollment at charter schools and smaller kindergarten classes due to lower birth rates. But the drop in fall 2020 was “five times larger than the largest decline previously observed.”

At the same time, enrollment in charter schools went up by more than 8,000 students. She said that some of the “missing” students probably went to home schools or private schools.

“And some students are missing from formal education entirely,” she said.

Meanwhile, back in September, staff from the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) gave lawmakers some info on actual attendance from students enrolled in the state’s public schools, and the news wasn’t great.

At that point, they said an average of 36% of students were completely remote. When it comes to virtual learning, either completely remote or partially, 19% of students, on average, were not attending regularly — defined as at least four days a week.

Fifty-nine percent of the state’s students were doing in-person learning at that point. And about 11%, on average, were not attending regularly.

Meanwhile, back to Tippett’s last point, about 15,000 of the state’s students were completely unaccounted for, according to DPI.

Terry Stoops, director of the Center for Effective Education at the John Locke Foundation, said some of this might be good news.

“Here’s where I’m optimistic, because chronic absenteeism was a serious problem long before the pandemic hit, and now that the public has been aware of the fact that there are significant numbers of students who aren’t fully participating in online education, I think it shines a light on an issue that we don’t talk about enough, which is attendance,” he said.

He said chronic absenteeism has a tremendous impact on a student’s ability to learn, and while the state has done a better job collecting data on this over the past few years, he hopes it becomes a central question of policy.

“How do we ensure that children attend school regularly and receive the full benefits of the public schools?” he asked. “It is absolutely essential that we answer that question in a way that ensures that chronic absenteeism becomes a rare event rather than a regular event.”

Matt Ellinwood, Education and Law Project Director at the North Carolina Justice Center, said that the enrollment declines and attendance issues were happening the most in areas of the state that are already under-resourced.

“It’s worrisome that that’s happening most in the lowest income districts,” he said.

He said he thinks enrollment and attendance will improve, but it’s possible they won’t completely recover. He said he thinks COVID-19 sped up some of the trends regarding movement of students to charter and home schools as well.

Overall, he said that most people are ready for students to go back to school in person, but that COVID-19 may mean some permanent changes to the way North Carolina does education.

“I think we will always have some virtual options, particularly at the larger districts,” Ellinwood said.

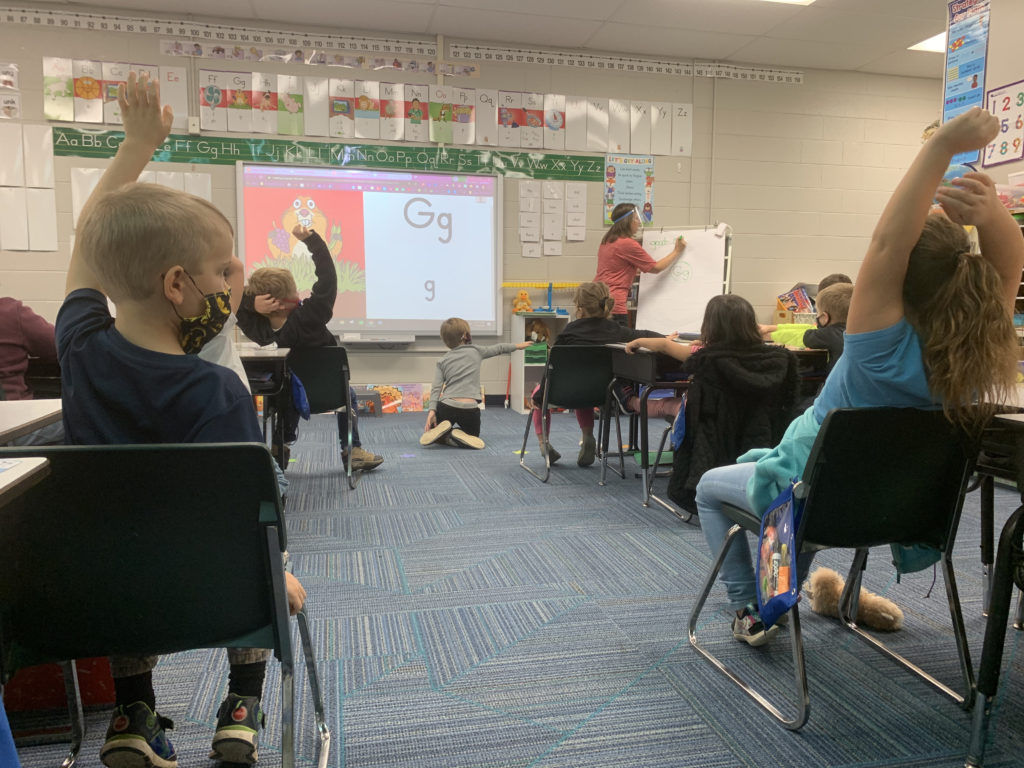

Teaching kids to read in a pandemic

By Rupen Fofaria

Devonya Govan-Hunt works with hundreds of Charlotte-area families, empowering them to become more involved in their students’ educations. One thing she heard often last year was surprise, and sometimes shock, about kids’ reading abilities.

“They say, ‘I thought my child was doing well until they had to stay home with me for school over the past few months, and now I realize that they’re not where the teacher said they were,’” said Govan-Hunt, president of the Black Child Development Institute of Charlotte.

As frustrating as it was for some parents to watch their children struggle with reading, a year in remote learning might have made things worse for many kids. During its March meeting, the State Board of Education heard results from students’ end-of-grade tests in 2019-20 (after a quarter spent in remote learning) and from students who took beginning-of-grade tests at the start of the 2020-21 school year.

The majority of third-grade students who took the beginning-of-grade reading exam scored at the lowest level. About 75% did not score at proficiency.

“We knew in the abstract that these test results would be disturbing, but it is even more difficult to see them on paper,” State Superintendent Catherine Truitt said in a statement. “The math and literacy results speak to a problem that predates COVID, and the pandemic has unfortunately exacerbated this problem.

“However, these results sharpen the Department’s resolve, and underscore why literacy will continue to be a statewide priority for us moving forward. We will not allow for this pandemic to be a generational hurdle that impacts students long term.”

Last month, the state enacted the Excellent Public Schools Act (EPSA) of 2021, which modifies the Read to Achieve Act and requires that all teachers in pre-K through fifth grade, as well as all teacher candidates in college, receive training in the body of research called the science of reading.

But that training will occur over the next three years, and full implementation of the law’s mandates isn’t expected any sooner. In the near term, the state hopes its summer program plan, enacted the same day as the EPSA, will help students who need it most.

Under that law, each district in the state must offer a summer program, lasting at least 150 hours or 30 days, to K-12 students to battle learning loss caused by the pandemic. The priority is for students with the highest needs, but other students can participate if space is available. The program is voluntary for families.

“Together, we can close the COVID gap and do great things for students in North Carolina,” Kim Morrison, superintendent of Mount Airy City Schools, told the House education committee in support of the bill.

In the meantime, community groups such as Read Charlotte are looking for their own answers. Read Charlotte is piloting a program called the Reading Checkup. It’s an app that families can download and prompts kids to take a short quiz. Based on the results, the app will recommend literacy games and activities.

“We use this as a supplement,” said Tiffany Burke, whose second grade daughter, Hollis, uses the app. “And she doesn’t feel like she’s in school when she’s doing it. She feels like she’s playing a game. So it’s been really helpful to me.”

Need for mental health and social emotional supports

By Rupen Fofaria

Identity, relationships, emotional maturity — every school-age kid is in some stage of self-definition. Schools are a primary venue for children to explore and build healthy lifestyles, relationships, and emotional development.

At least they were, until the pandemic closed school buildings last year and prevented normalcy through most of this one. Particularly in the beginning, based on recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and on local coronavirus statistics, educators were forced into an unfamiliar territory.

“What we were telling (students) to do was basically in direct opposition to what we would normally say is healthy behavior,” said Jodi Deskus, the student assistance program coordinator at Wake Forest High School. “We were saying you need to isolate. We were saying you need to be on a device all the time. We were saying that you need to not be socializing regularly. We were saying that you don’t need to come to school or participate in any activities, sports or otherwise.”

Concern about student mental health increased during remote and hybrid learning. Student experiences drove some concerns — hearing about kids who were too busy caring for sick parents and helping younger siblings to log on for class; watching kids who thrived in school suddenly fail classes. But the worst, Deskus said, was when you didn’t know the student’s story at all.

“Our ability to really keep our finger on the pulse of how our students were doing was severely compromised,” she said. “And then that was coupled with a county that was trying to figure out, as quickly as possible, how to keep things like the confidentiality of our students, the safety of our students, as paramount.”

Studies don’t always agree on the impact the pandemic and remote learning has had on students, particularly on their mental and emotional health. But teachers don’t need studies to identify trouble. Educators statewide reported high failure rates, low and inconsistent attendance, and myriad challenges offering mental health services.

That’s the challenge facing students and educators, who hope for a return to normalcy in the fall. But while the pandemic deepened mental health concerns, some of the problems existed before COVID-19.

For years, the state has lagged behind national averages in staffing for mental health professionals.

- The nationally recommended ratio for school counselors is 1:250, and North Carolina’s ratio is 1:367.

- The nationally recommended ratio for school psychologists is 1:500-700 students, and North Carolina’s ratio is 1:1,943.

- The nationally recommended ratio for school social workers is 1:250, and North Carolina’s is about 1:1,500.

- The nationally recommended ratio for school nurses is one per school, or about one per 750 students. North Carolina’s school nurse ratios range from less than 1:750 to 1:2,322. Forty-four percent of school nurses in North Carolina serve just one school — others serve up to five schools at once. Fifteen percent of school nurses serve three or more schools.

Bringing these numbers up is key to ensuring students have access to the resources they need. Gov. Roy Cooper included funding for increasing staffing in these positions in his budget, recommending $40 million in recurring funding for positions such as nurses, counselors, school psychologists, and social workers.

Letha Muhammad of the Education Justice Alliance says things like staffing increases in these positions or having trauma specialists in place are especially important to address lingering impacts of the pandemic on kids. This is particularly important from an equity perspective, she says, considering that Black and Brown kids historically are disciplined at higher rates in schools.

“The reality is that young people, as well as adults, have been living through a lot of trauma as the result of a global pandemic,” Muhammad said. “I just worry about what that means when more young people are back in school. How will that trauma manifest in those spaces?

“And we’re talking about traumatized young people as well as traumatized adults. It’s a potential, in my mind, for a disaster, because we may miss the opportunity to recognize that a young person is acting out as the result of trauma and it could further push, in particular Black and Brown students, out of schools.”

The Department of Public Instruction has lifted mental health up as a budget priority since Catherine Truitt became superintendent this year. In February, Truitt said she’s requesting nearly $56 million from the General Assembly for student mental health, well-being, and school safety.

Assessing learning in a pandemic

By Alex Granados

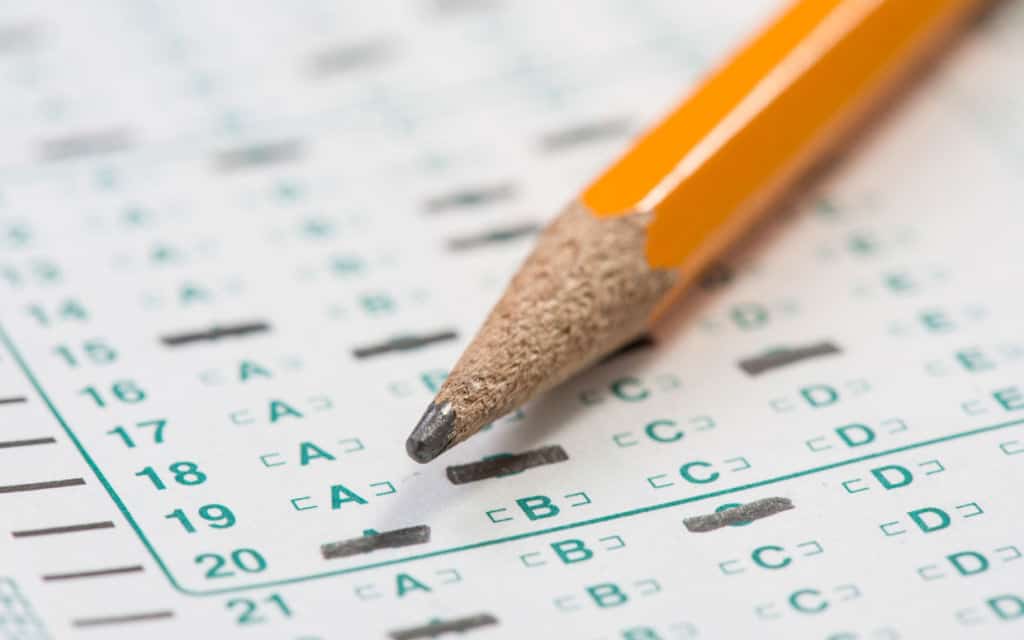

The pandemic threw a wrench in the always-controversial testing and accountability structure in North Carolina.

Like clockwork, schools throughout the state offer end-of-course tests, end-of-grade tests, and other “high-stakes” assessments, which are used to form the state’s school report cards and assign grades to schools. The results of such tests are even instrumental in determining how much money a principal is paid each year. So when COVID-19 hit, one of the first questions was what the state was going to do with testing and accountability.

Last spring, the state received waivers for federal testing and accountability requirements. And lawmakers also granted waivers for the requirements in the state statute. That meant no standardized tests, no school performance grades, no third-grade retention, and no summer reading camps. In fact, in some cases, it also meant no grades for students.

Things are different this year. The federal Department of Education under former President Donald Trump made clear in the first part of the school year that states could not skip standardized tests altogether. In the fall, that meant that end-of course tests and Career and Technical Education assessments had to happen. It also meant students in third grade must take their beginning-of-grade test. The tests also had to be taken in person.

Recognizing how hesitant some districts would be — given how many students were in remote learning — the state did offer flexibility on when such tests could be taken. For instance, districts had until June 2021 to give students their fall end-of course tests.

When President Joe Biden took over in January, there was hope that federal testing requirements might be adjusted so that students could skip them this year. That did not happen. The federal government did, however, give waivers on accountability measures, and if state lawmakers sign off on similar waivers, things such as school performance grades, school report cards, and low-performing school and district designations will be halted for this year.

What, if anything, does any of this mean for the future?

Matt Ellinwood, education and law project director at the North Carolina Justice Center, said he is happy that there will be testing this spring.

“I think we need to see where the areas hardest hit are,” he said, noting that lower-income communities and communities of color were hit harder by the pandemic, and test scores probably will reflect that.

But he said he’s also hopeful that the pandemic has shown the need to measure more about students than just academics. He said metrics for things such as social and emotional health, resources in schools, and what tutoring or advanced placement is available would all be helpful.

“I can see that potentially happening because people just want to know what they’re going back into,” he said. “What are the resources available in the school to help overcome what’s just happened?”

Terry Stoops, director of the Center for Effective Education at the John Locke Foundation, said he doesn’t see the state’s testing regime changing much.

“There will continue to be resistance from teachers’ organizations and others who believe it’s an inaccurate assessment of student achievement. We’ll continue to see parents objecting to standardized testing,” he said, adding that the reason we have these tests is because “elected officials compel” them.

He said he doesn’t think either the Biden administration or the General Assembly has much “motivation or willingness” to dramatically cut testing, though he could see some more subtle changes happening. For instance, schools or school districts may cut back on locally administered assessments. And North Carolina as a whole might move toward a system of smaller tests throughout the year.

He thinks changes to accountability measures such as school performance grades and report cards are possible as well.

“The way that we communicate testing to the public, that may change,” he said. “And perhaps if we find ways to better communicate how students are performing then that may be something that both parties in the General Assembly could agree to and certainly would be welcomed by parents who may be confused by the current system of how schools are graded.”

Exposing the digital divide

By Analisa Sorrells

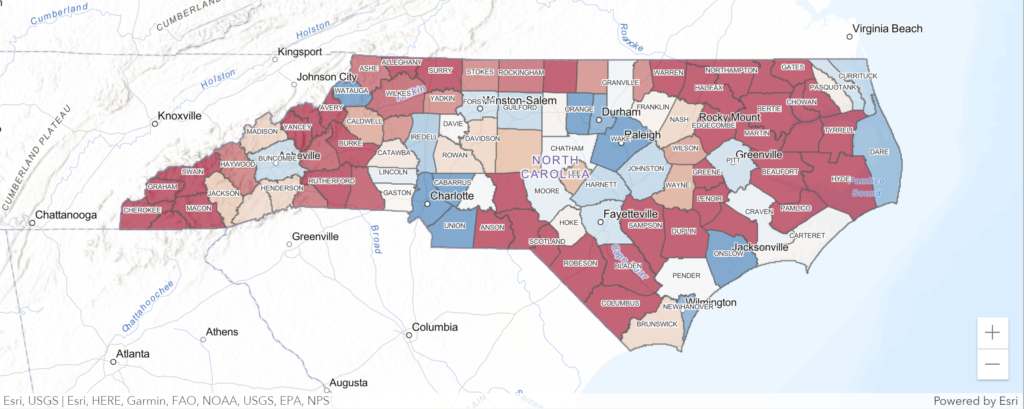

When the pandemic forced districts to close school buildings and shift instruction online, North Carolina’s digital divide became front and center. While every school district is connected to high-speed fiber internet via MCNC, at-home access for students is a different story.

The barriers to broadband internet access for students and families are complex and layered. These issues are often talked about as the three A’s: access, affordability, and adoption. Rural areas are sparsely populated, making it more difficult for companies to get a return on broadband investment there. That leaves some communities with one or no broadband internet providers. Then there are the adoption and affordability issues — people may not see a need for a high-speed internet connection, or, more likely, can’t afford one.

The state’s Broadband Infrastructure Office publishes indices on both broadband availability and broadband adoption by county and census tract. According to those indices, as of 2019, almost 16% of households statewide did not have internet access.

In the early days of the pandemic, school districts turned to quick solutions to ensure that students could participate in remote learning. Guilford County Schools deployed “smart buses” equipped with Wi-Fi to park in locations across the district, and Lincoln County Schools provided Wi-Fi in school parking lots. But those solutions required parents to take students to access points. Other districts provided students with hot spots to use at home, but those require cellular service and often have data limits.

When it comes to long-term solutions to connecting households to broadband internet, North Carolina is deploying a range of technologies, depending on the community. Ray Zeisz, senior director of the Technology Infrastructure Lab at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, says every broadband technology has pros and cons.

Almost 40% of North Carolinians have access to high-speed fiber, but building out last-mile fiber to homes requires expensive infrastructure, making it unlikely that fiber will be offered to every household in the state.

Wireless solutions allow broadband internet to reach further into a neighborhood without having to run fiber to each home, which can reduce the total cost. However, wireless internet towers are expensive, and there are regulations that restrict their installation.

Satellite solutions, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, which is being piloted in two North Carolina school districts, don’t require cables or a wireless tower. Instead, a dish connects with satellites orbiting in space and delivers internet access to the home.

Before the pandemic, North Carolina had a range of initiatives related to increasing broadband access, including a state broadband plan, the School Connectivity Initiative, and the GREAT Grant program, which funds private providers to deploy broadband service in unserved areas.

“I don’t think that there’s anything really new that needs to be invented,” Zeisz said. “I think we knew years ago what needed to be done. It’s just now getting the funds to actually flow.”

And while education is the focus of many broadband initiatives right now, Zeisz sees numerous economic implications of internet access for North Carolina’s future.

“You really have to look at: What is the economic impact, and how do we make the state more competitive both nationally and globally, in terms of precision farming, advanced logistics and tracking, and better power grid management?” he said. “There are actually economic drivers that we won’t really get to see the impacts of on a wide scale until we have a little bit more deployment.”

Another concern related to remote learning is how much screen time is appropriate for children. In 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that children under 18 months avoid the use of screens. For children ages 2-5, AAP recommended a limit of one hour per day of high-quality programming. For children ages 6 and older, the recommendation is to place “consistent limits” on screen time and not let it interfere with children’s sleep or exercise habits.

Those recommendations pertain to screen time of any kind — including attending a virtual class, completing homework online, watching television, using apps on tablets, and using a smartphone — which can add up quickly, especially for students engaging in remote learning. Here is an online tool that parents can use to calculate screen time and make a personalized family plan.

Resources | For a map of public Wi-Fi locations around the state, click here. To take a survey and internet speed test, which will help the state identify areas without sufficient broadband, click here. And to learn more about the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program, which will subsidize the cost of home internet access for low-income families, click here.

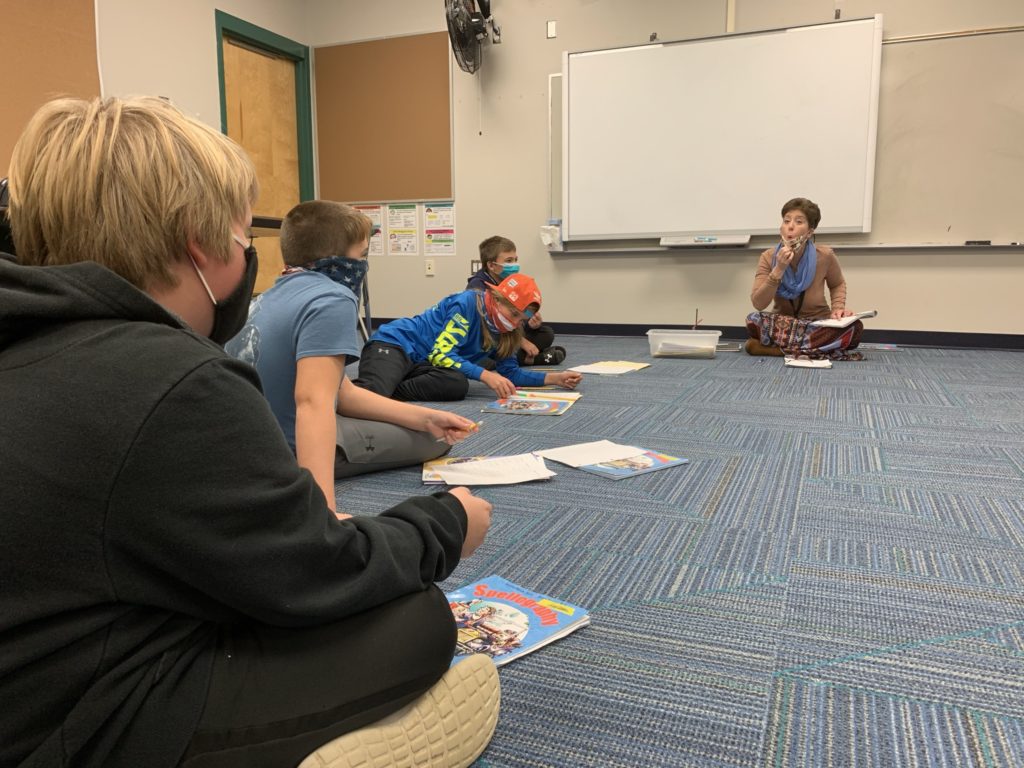

A new tutoring corps

By Molly Osborne

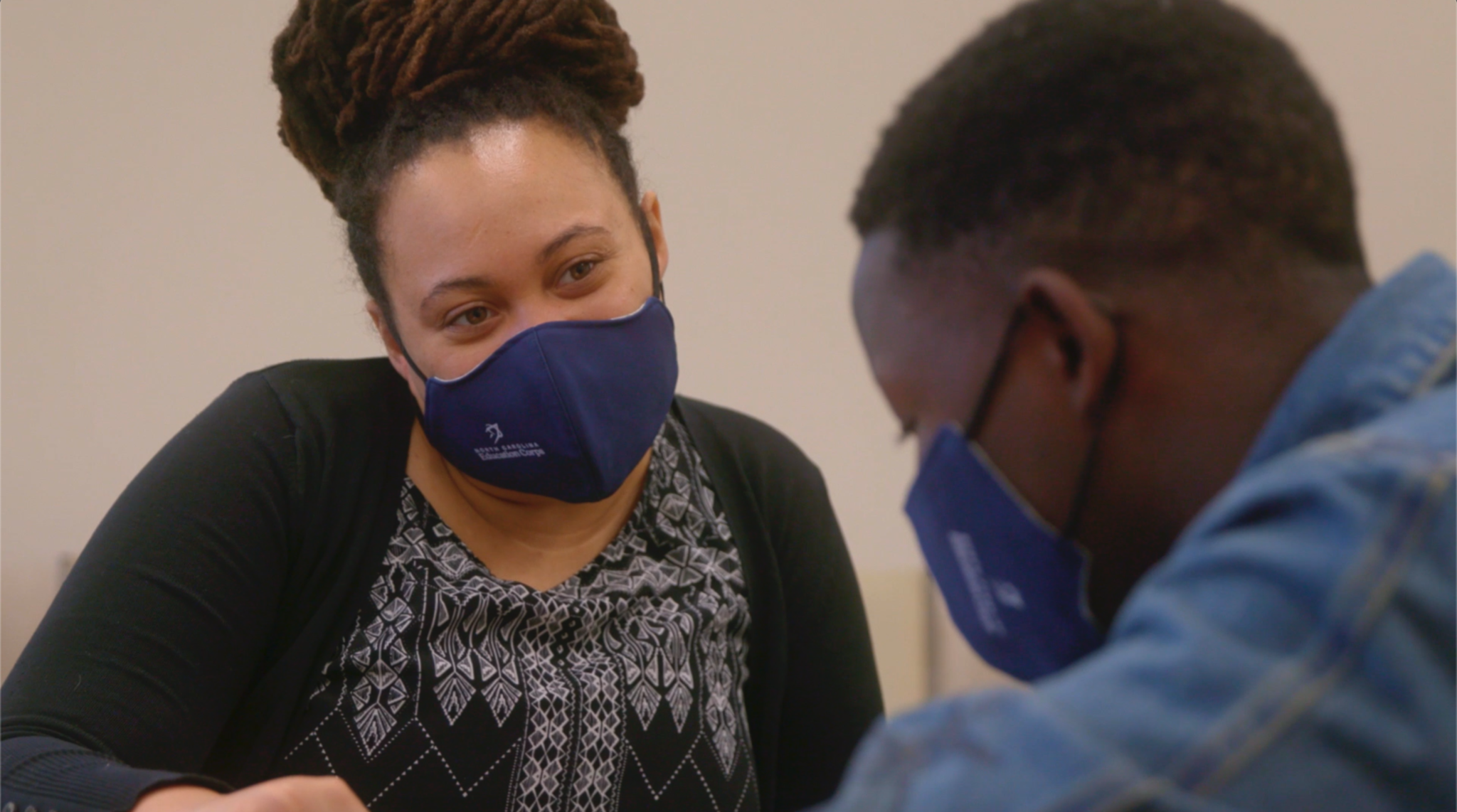

As it became clear that the pandemic would radically disrupt education, policymakers across the country began looking for ways to minimize the negative impact on learning. One of the solutions that emerged was the idea of large-scale tutoring initiatives.

In a report on COVID-19 and learning loss, McKinsey & Company identified “high-intensity tutoring” as one strategy to catch up on lost learning, stating, “A proven catalyst for accelerated learning is one-on-one support for students.”

National organizations and education leaders, including former U.S. education secretaries, pushed for a national volunteer tutoring force. In Tennessee, the Bill and Crissy Haslam Foundation launched the Tennessee Tutoring Corps, which paid college students a $1,000 stipend to tutor students in math and English over the summer.

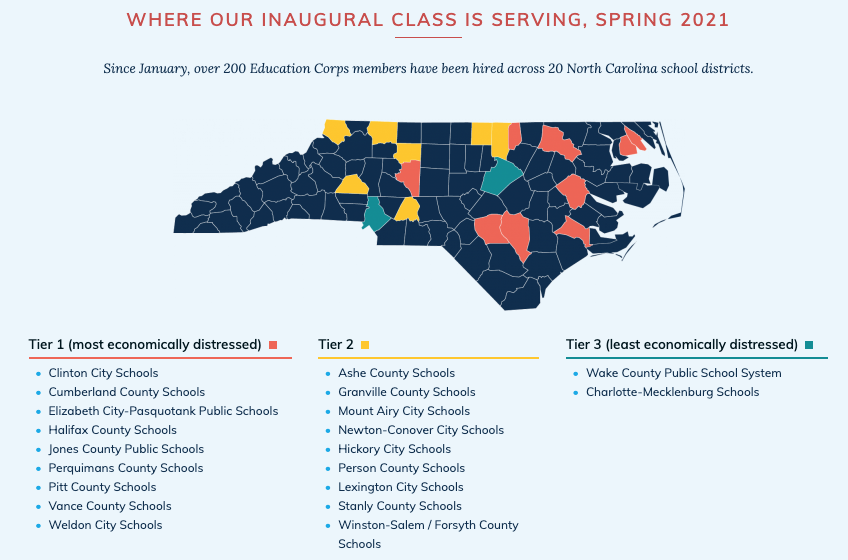

In North Carolina, the State Board of Education, the governor’s office, the nonprofit organization American Ripples, and local public school districts joined to create the North Carolina Education Corps, a project to provide support to school districts while creating jobs for North Carolinians.

“If you take our state’s longstanding commitment to public education and our tradition of taking care of fellow North Carolinians, and you put those two thoughts together, then you get the NC Education Corps,” said State Board of Education chair Eric Davis.

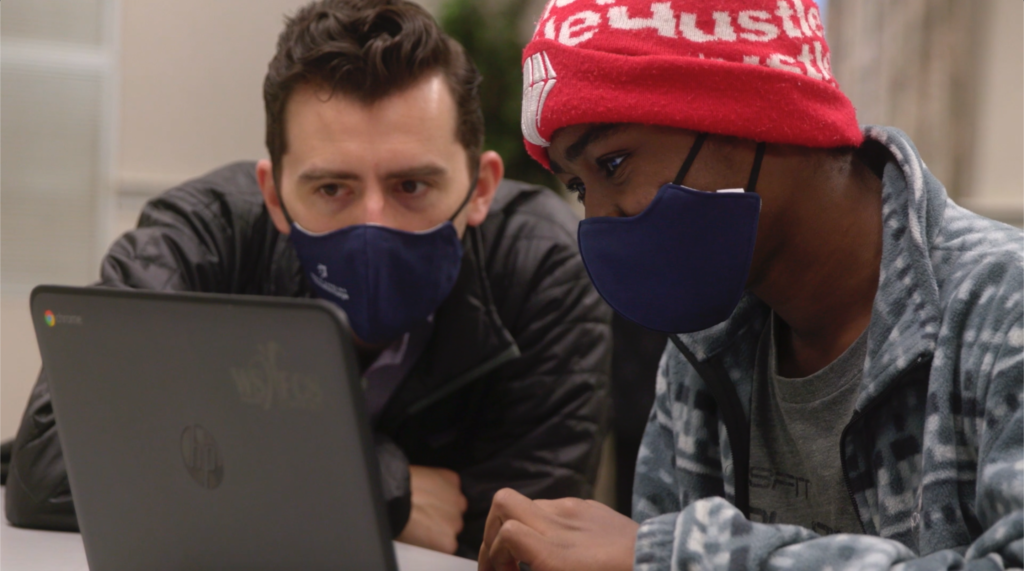

The inaugural cohort of the NC Education Corps launched in January 2021 and has grown to include just over 200 members working across 20 school districts. Corps members commit up to five months and are expected to work anywhere from 10-15 hours a week to 20-30 hours per week. They are paid at least $13.50 an hour by the school systems.

In its first year, corps members served in three primary roles — tutors, mentors, and contact tracers — said program director John-Paul Smith.

“This year has really been about emergency response,” Smith said. “In many cases, districts have needed corps members to start with … how do we re-engage students who are not showing up to class or are not turning in their work, provide any kind of social emotional support that they need that might help them re-engage in school, and then only after that get back to the academic support parts.”

The corps members come from a variety of backgrounds, but the two biggest groups are four-year and community college students and retired teachers, Smith said. For college students interested in teaching, the corps provides an opportunity to experience being in a classroom before fully committing to a career in education, Davis said, highlighting the importance of the corps as a teacher recruitment pathway.

Moving forward, Davis sees the Education Corps as a vital part of North Carolina’s education system.

“The catalyst for this was initially around COVID learning recovery and helping our students who’ve been so impacted by the pandemic,” Davis said. “But it is growing beyond that to becoming a permanent element in the way that we care for our students and educate them.”

This upcoming school year, corps members will serve exclusively as K-3 literacy tutors, Smith and Davis said.

“The initial thought was meeting the needs of districts,” Davis said, “but as we began to work more and more closely with districts, it became apparent that one of the overriding needs from an academic standpoint was literacy. Every district needs help with that.”

Smith said corps members will receive training in the science of reading, a body of research on how the brain learns to read and effective instructional practices, and specifically focus on helping students build their phonemic awareness and phonics skills.

The NC Education Corps hopes to grow to 1,000 corps members serving in every district, Davis said.

“I could not be more pleased,” Davis said, speaking of the efforts they’ve seen this year from corps members and school districts. “It makes me really proud to be a North Carolinian.”

Fewer disciplinary issues

By Sergio Osnaya-Prieto

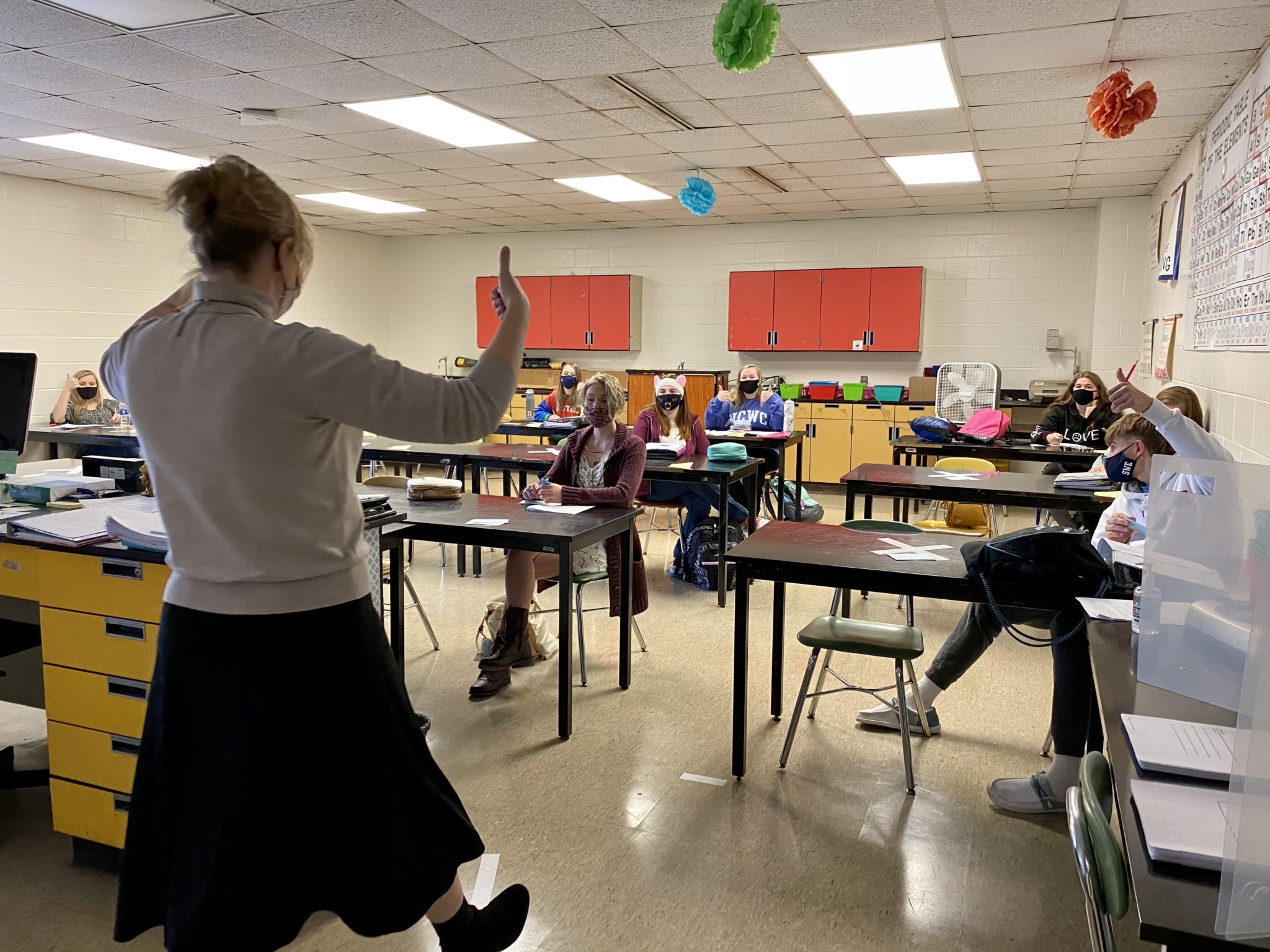

Student discipline issues dropped throughout the 2020-21 school year because of changes to remote instruction and the smaller class sizes required by social distancing rules during the pandemic, according to K-12 teachers across the state.

Michelle Wall, an assistant principal at James W. Smith Elementary School in Craven County, said teachers in her school had reported only four major disciplinary incidents — requiring office referrals — and 22 minor incidents as of April 23. During the 2019-2020 school year, teachers reported 155 major incidents and 278 minor incidents.

“I really wish the legislators would look at class size and … increasing the number of teachers, because I have seen what class size does to this place,” Wall said. “You have fewer kids in there, they get more one-on-one attention. They’re not misbehaving to get attention.”

Jessica Caldwell teaches at Clyde Campbell Elementary, which was under plan B — a hybrid of remote and in-person instruction — until mid-April. She said her school has had basically no discipline problems this school year, a trend she attributed to smaller class sizes.

“And with (students) only being there two days a week for most of the year, they didn’t want to argue when they finally got to see their classmates and their friends,” she said. “They wanted to get along because they only got to stay in for two days.”

The state Department of Public Instruction’s annual report on school crime, suspensions, and other disciplinary issues for the 2020-21 school year is not available yet. DPI’s report on student discipline from the 2019-20 school year, however, shows a “significant reduction in the number of incidents” reported by schools after the shift to remote instruction in March 2020.

According to the 2019-2020 data, Black male students had the highest rate of short-term suspension, followed by American Indian males. Of the 152,873 short-term suspensions in 2019-2020, 146,657 (96.0%) were given as a result of an incident involving unacceptable behaviors.

Within that category of unacceptable behaviors, Black, American Indian, economically disadvantaged, and students with disabilities had the highest rates of suspensions. Black students also received the most long-term suspensions (206), followed by white students (116). Black students comprised 24% of the state’s public school students compared to 46% white students, according to the Department of Public Instruction.

At Fuquay-Varina Middle School in Wake County, teachers saw a drop of more than 85% in student discipline issues compared with the previous year, said Laura Griffith, who teaches sixth through eighth grades.

“I do feel like it is comparing apples to oranges … in-person versus virtual,” Griffith said. “But I feel like that is an advantage to virtual learning … there’s not as much opportunity to have disruptions in classrooms.”

Changes to the number of students allowed on buses and cafeterias also reduced the number of opportunities for disciplinary issues in some schools. John Heath, an assistant principal at Perry W. Harrison Elementary in Chatham County Schools, said teachers and students at his school ate together in classrooms instead of a “crowded cafeteria.”

“That was another opportunity to kind of create community,” Heath said, “and the teachers are able to more closely supervise during the lunch period.”

Heath said the decrease in disciplinary issues could also be attributed to his school’s Responsive Classroom approach, which focuses on building that sense of community and the social-emotional health of students.

Students were also less likely to misbehave or have disciplinary issues simply because they were glad to see their peers again after long periods of remote instruction, Wall said.

The steep decrease in disciplinary issues has been good for teachers, too, she said.

“The teachers seem happier, like you can see when they get frustrated, because, ‘Oh my goodness, it’s the same kid over and over,’” Wall said. “But they really aren’t having that. Again, they’re able to give more attention to each child.”

On May 6, a bill that changes standards of student conduct in North Carolina schools passed the House on a party line vote, with Democrats voting against and Republicans voting for. The most significant change the bill makes is removing from current law the following examples as things that should not be considered serious actions on the part of students.

- Inappropriate or disrespectful language.

- Noncompliance with a staff directive.

- Dress code violations.

- Minor physical altercations that do not involve weapons or injury.

This is an important distinction because long-term suspensions and expulsions in public schools are supposed to be limited to “serious violations” of student conduct codes. The examples now being removed were first added to state law back in 2011 out of a recognition that not having students in school can contribute to “behavioral problems, diminish academic achievement, and hasten school dropout.” The bill now goes to the Senate.

Crumbling infrastructure laid bare

By Dean Drescher

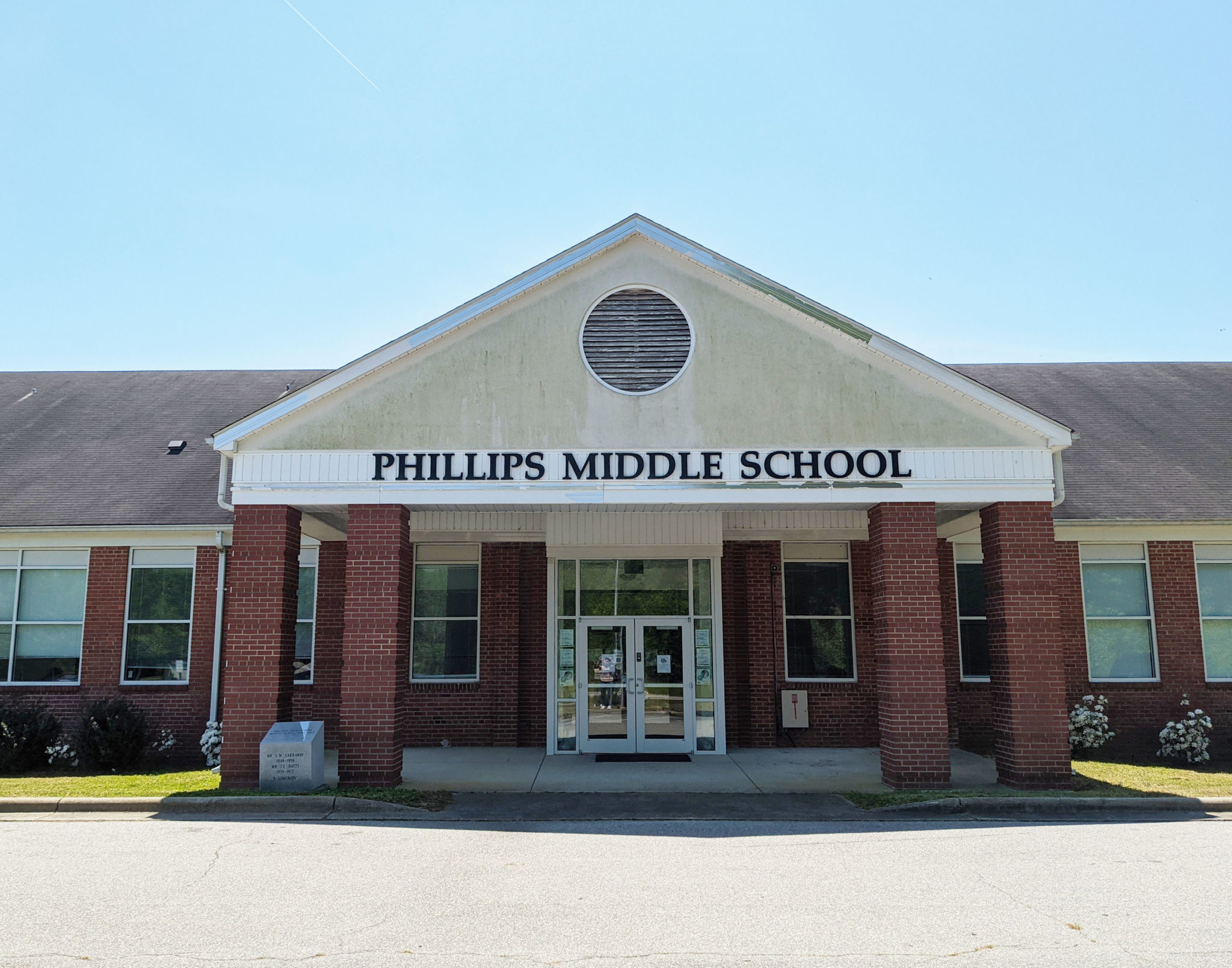

It was cold in January, and Jenny O’Meara had a decision to make. All winter, Phillips Middle School, where O’Meara is principal, had no working heat.

In some ways, the pandemic made this less of a problem — students weren’t there. But, after the Edgecombe County School Board voted to allow middle schools to reopen, O’Meara faced a dilemma: Bring students back into the Phillips building to learn in the cold, or find another place for the students to go and work through making that space COVID-19-safe.

“It almost was like a joke here, like, ‘What else can this year throw at us?’” O’Meara said.

The situation at Phillips — an aging, rural school building with broken heat — is far from unique. A 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that more than 36,000 public schools nationwide needed updates in their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems. More than half of public school districts need to repair or replace multiple building systems (roofing and light fixtures, for example).

“I got to a point where I … was just like, I’m just going to make a proposal to change schools because what I’m not going to do is bring kids back into this building when we don’t have heat,” O’Meara said.

O’Meara felt lucky that neighboring North Edgecombe High School granted her and her students access to empty spaces on that campus, but the challenges of reopening a middle school in a high school during a pandemic were apparent.

“I went … and measured out every classroom to make sure, like, can we put kids in here six feet apart? And we barely, I mean we just made it,” O’Meara said. About 70 Phillips students had opted to return in person. Had there been more, O’Meara said, she isn’t sure her temporary solution would have worked.

While many problems facing school buildings may not be a direct result of COVID-19, the pandemic has often laid them bare or complicated them. Improvements to air filtration systems and broadband internet access gaps have been highlighted, but for those and for other less-discussed pesky problems — like the broken heat at Phillips — the pandemic may also have ushered in some solutions.

The American Rescue Plan, which allocates $125.4 billion for K-12 schools nationwide, is a massive, one-time infusion of federal funding, with school superintendents and boards carrying substantial responsibility in administering the funds.

North Carolina is set to receive about $3.6 billion for K-12 schools. That’s on top of $396 million in previous federal money from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and $1.6 billion from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of December 2020 (CRRSAA), per data from the Southern Regional Education Board. These dollars are generally intended for schools to create a safe environment for in-person learning.

American Rescue Plan funds have “the widest set of allowable uses,” according to Andy MacCracken, a policy analyst with the Pandemic Recovery Office, the state agency responsible for coordinating COVID-19 relief funds. “It’s also the largest pot and can be used for the longest.” Its uses can include upgrades or repairs to HVAC systems, MacCracken said.

Faced with many challenges due to the pandemic, along with a hefty influx of money, it’s unclear whether education leaders will opt to use incoming funds on school buildings and infrastructure needs.

But the students, O’Meara said, do notice what repairs or upgrades need to be made. And perhaps for good reason — a 2019 report from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health synthesized more than 200 studies on the impacts of environmental qualities of school buildings on students. “The evidence is unambiguous,” it said. “The school building influences students’ health and academic performance.”

“Kids, they notice it and they make meaning out of it, right?” O’Meara said. “Like, if my school looks this way, here’s what this means about me and my community. And here’s what it means about the value that the school system puts on me and my community.”

Phillips Middle School students returned to their building in April. Heat may not be needed in spring, but, while wrapping up our visit, O’Meara pointed up.

“Leaky roofs,” she said.

The importance of school meals

By Analisa Sorrells

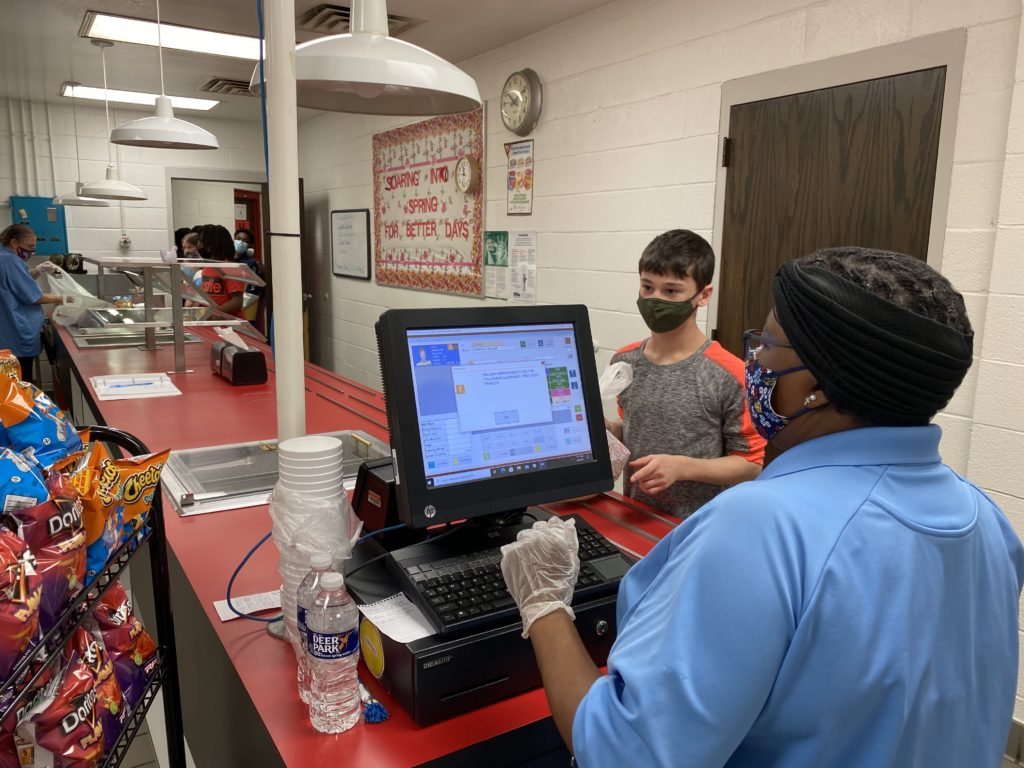

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated one in every five children in North Carolina struggled with hunger, and almost 60% of students enrolled in North Carolina’s public schools qualified for free or reduced-price school meals.

When school buildings closed in March 2020, districts throughout the state sprang into action to serve school meals in new ways. Some deployed school buses to deliver meals door-to-door, and others set up curbside drive-thru lines where parents could pick up a week’s worth of food.

School nutrition employees suddenly found themselves on the front lines of the fight against increasing rates of hunger as the pandemic took an economic toll on families. An analysis of the Census’s Household Pulse Survey estimates that food insecurity in North Carolina increased from 11.7% in February 2020 to 24% in April and May 2020.

Innovative approaches to serving school meals were enabled by waivers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that allowed school nutrition departments to work outside the usual bounds of school meals. Rather than serving meals under the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP), schools could serve them under the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) — a federally funded, state-administered program that provides reimbursements from the U.S. Department of Agriculture for any free meal served to a child age 18 and under.

Other federal waivers meant that parents could pick up meals without children present, multiple meals could be offered at one time, and meals could be served in non-congregate settings (i.e., drive-thru or grab-and-go). In Thomasville City Schools, these flexibilities allowed the nutrition department to serve five times the number of students enrolled in the district, as younger siblings and students from surrounding communities also qualified for the free meals.

According to Mary-Catherine Talton, child nutrition director in Wilson County, the fact that all students could receive free meals, regardless of socioeconomic status, was crucial to both keeping their doors open and keeping students fed, “because there were a lot of families that were not disadvantaged going into this, but suddenly became disadvantaged,” she said.

Despite these efforts, the number of students receiving school meals statewide decreased from pre-pandemic numbers, and that meant less income for school nutrition departments. According to a May 2020 presentation from the state Department of Public Instruction, COVID-19 caused the number of reimbursable meals served statewide to fall from roughly 1.2 million per day to 500,000 per day. The result was an estimated shortfall of $7.6 million in school nutrition revenue per week.

As school buildings gradually reopened throughout the 2020-21 school year, districts shifted their approaches, often serving meals in the school building for students attending in person while still operating curbside drive-thru or delivery service for remote students.

Then, on April 20, 2021, the USDA announced that several school nutrition waivers were being extended through June 30, 2022. They had been set to expire at the end of September 2021. Among the waivers include the option to maintain grab-and-go stations and curbside pickup for remote learners.

Another waiver provides the option for schools to serve meals all school year through the Seamless Summer Option (SSO), which is usually available only during the summer. The SSO allows schools to serve free meals to all students, meaning school nutrition staff will not need to verify student eligibility for free meals. Schools that operate the SSO will also receive higher-than-usual reimbursement rates for each meal served.

Beyond these policy changes, Talton said, the pandemic has also prompted her school nutrition department to become more integrated with the rest of the district. It was all hands on deck — from technology to maintenance to transportation. Talton recalled not knowing the transportation director very well before, but two weeks into the pandemic, they were talking every day to get food onto buses and delivered to students.

“While it has been very challenging and heart wrenching, and the most stressful thing I’ve ever done in my life, it has also had a lot of good outcomes … to put school nutrition kind of at the forefront of everybody’s mind,” Talton said.

Recommended reading